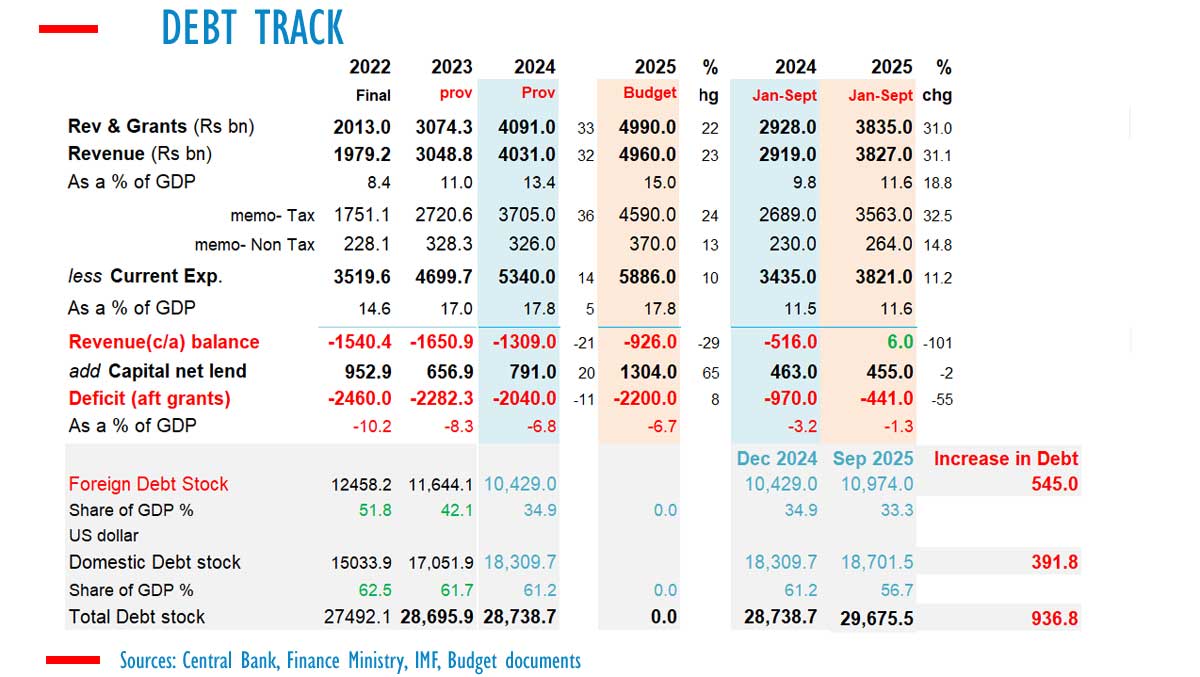

According to official data, Sri Lanka’s central government debt increased by 936 billion rupees by September 2025, despite the budget deficit being only 441 billion rupees. This rise in debt occurred as foreign debt expanded, even amid a net repayment, due to rupee depreciation.

The budget deficit decreased to 441 billion rupees by September 2025, down from 970 billion rupees, despite a salary hike for state workers. This improvement was facilitated by tax collections amounting to 3,563 billion rupees, up from 2,689 billion the previous year, as per central bank data.

Yet, the central government debt grew by 936 billion rupees, more than twice the budget deficit, with foreign debt increasing by 545 billion rupees to 18,974 billion by September 2025, from 10,429 billion at the end of 2024.

In 2025, the Sri Lankan rupee depreciated, despite record current account surpluses and better budget performance, challenging the usual macroeconomic explanations for currency devaluation.

In Sri Lanka and other countries frequently seeking IMF assistance, there is a common narrative that exchange rates are “market determined.” However, EN’s economic columnist Bellwether clarifies that “exchange rates are not market determined. The price of carrots and beans are market determined.”

Bellwether explains that, “If the value of money were market-determined, the economy would revert to a primitive barter system. This is the reality for countries lacking stable currency. While interest rates are market determined, exchange rates are anchored by the central bank’s operating framework. In a clean float, the currency’s value is dictated by monetary policy, usually linked to an inflation index. In a hard peg or currency board, the value is determined by exchange rate policy.” In contrast, a “flexible exchange rate regime or soft-peg results in currency instability due to arbitrary exchange rate and monetary policy applications.”

Bellwether further notes that central banks began depreciating currencies at will following the IMF’s second amendment to its articles, after the Bretton Woods collapse, leading to multiple defaults in Latin America during the 1980s.

Sri Lanka’s President Anura Kumara Dissanayake emphasized the need to maintain a stable exchange rate in his budget speech. Politicians face accountability for depreciation when food and energy prices rise, and taxes are increased to manage national debt.

Up to September, foreign debt expanded in rupee terms despite a net repayment, with the deficit being financed by 515.3 billion rupees in domestic financing and a net repayment of 93.6 billion rupees in foreign debt. In 2025, the Treasury purchased some dollars for rupees from the Central Bank to repay debt. However, analysts recommend the Treasury buy dollars independently without relying on the central bank, as its ability to collect dollars may diminish if inflationary open market operations resume.

Under flexible inflation targeting and current monetary laws, the central bank is not legally obliged to implement deflationary policies to provide current account dollars to the government for debt repayment. To build reserves from current inflows, the central bank must peg and run deflationary policy at an appropriate interest rate.

Following the May rate cut, the central bank has fallen short of reserve projections, despite increased tax payments. Analysts highlight that monetary debasement, inflation, and currency issues are legal and political problems arising from parliament’s inability to control the central bank, which lacks accountability.

Bellwether asserts that “it is up to the parliament to control the central bank, which has been granted various monopolies and privileges, forcing people to accept its money.” He recalls how the British parliament, with vast knowledge of money in the classical period, maintained accountability, making Sterling the world’s leading currency and the UK a free-trading industrial exporter.

The central bank has also been granted a de facto ‘Government Acceptance’ privilege, allowing taxes to be paid in rupees, obstructing non-debt dollar revenue streams to the Treasury. While the Treasury does not purchase dollars in the market to repay debt, increasing the likelihood of a second default, other ministries buy dollars for import bills. (Colombo/Dec30/2025)