A country that declared bankruptcy, entered IMF-led restructuring because it could not repay external debt, and spent years under severe import compression is now on track to spend USD 1.7 billion on vehicle imports in 2025, exceeding Sri Lanka’s exports to the United States. That single fact alone should give policymakers pause.

Central Bank data show that November 2025 recorded USD 281 million in vehicle imports, the second-highest monthly level of the year, just below September’s USD 286 million peak. After a brief dip in October, imports rebounded, pushing cumulative vehicle imports to USD 1.7 billion by end-November, with the IMF projecting the total could reach USD 1.8 billion, well above earlier official forecasts. This is not a marginal overshoot—it is a material deviation in a post-default economy where foreign exchange discipline should remain paramount.

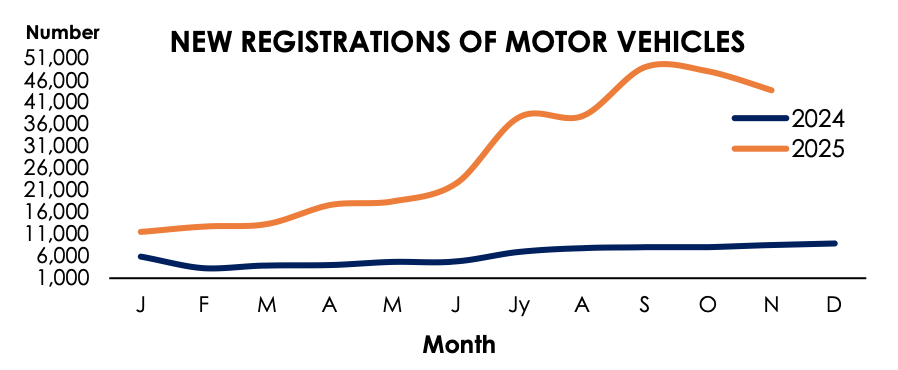

Import volumes tell an equally important story. Central Bank statistics indicate monthly vehicle imports in 2025 have surged back to 6,000–9,000 units, close to pre-crisis levels last seen in 2018–2019. This rebound has been rapid and front-loaded, not gradual. Sri Lanka has moved from near-zero imports during the crisis years to near-normal volumes within months of lifting the five-year import ban in February 2025.

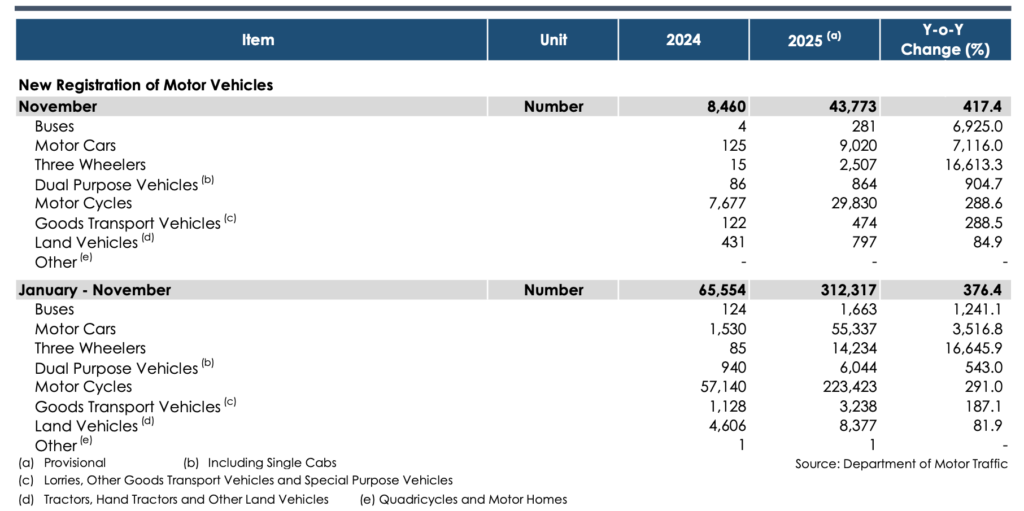

Crucially, vehicle registration data confirms this is real domestic absorption, not just backlog clearing. By end-November 2025, 312,317 new vehicles had been registered, compared with just 65,554 a year earlier. Motorcycles accounted for over 223,000 units, motor cars exceeded 55,000, and even buses, three-wheelers, and goods vehicles recorded explosive year-on-year growth. November alone saw 43,773 new registrations, more than five times last year’s level. While base effects inflate growth rates, the scale of the rebound leaves no doubt that private vehicle consumption has returned at speed.

Supporters argue that the surge is easing. The Central Bank notes a decline in Letters of Credit since mid-year and easing vehicle prices, suggesting pent-up demand is being absorbed. The Committee on Public Finance and the CBSL also expect demand to moderate in 2026. That may well happen—but moderation after a spike does not erase the macro risk created by the spike itself.

Two deeper concerns remain.

First, today’s vehicles cost more foreign exchange per unit than in the past. The import mix has shifted toward hybrids, EVs, and higher-end models. As a result, even volumes merely approaching pre-crisis levels now translate into much larger FX outflows. This explains why Sri Lanka has reached USD 1.7 billion so quickly—and why the IMF expects a further overshoot.

Second, the fiscal dependence on vehicle imports is dangerous. Government revenue in 2025 has exceeded projections largely due to vehicle import taxes, helping the primary balance outperform. But this is a volatile, externally draining revenue source. The same Committee on Public Finance has already warned that this boost will likely fade in 2026. Sri Lanka has seen this movie before: import-fuelled revenue masks underlying weaknesses until the external constraint snaps back.

The issue is not whether Sri Lanka should import vehicles. After years of forced suppression, some rebound was inevitable. The issue is pace, scale, and prioritisation. A bankrupt country under IMF supervision cannot afford to behave like a surplus economy. Spending more on vehicle imports than what the country earns from exports to major markets raises a fundamental question: are scarce dollars being deployed to strengthen future earning capacity, or to satisfy deferred consumption?

Without clearer guardrails—such as differentiated tariffs favouring commercial and productivity-enhancing vehicles, limits linked to reserve performance, and tighter credit oversight—Sri Lanka risks recreating the same external imbalances that led to collapse. True recovery is not measured by how quickly car showrooms refill or registrations surge, but by whether today’s policy choices reduce the probability of the next crisis.

On that test, USD 1.7 billion on vehicles in a post-bankruptcy year is not a sign of strength—it is a warning signal.