Sri Lanka’s Most Creative Fiscal Innovation “Confidence is not an accounting standard”

Not long ago — close enough that no one can plausibly plead amnesia — the Central Bank assured the country that Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange reserves stood at a reassuring USD 6.4 billion. This figure was repeated solemnly, cited defensively, and deployed as proof that the worst was behind us.

Shortly thereafter, the government did something interesting.

It lifted the embargo on vehicle imports, opening the gates to an estimated USD 1.7 billion worth of demand. This was framed as normalisation, confidence, economic breathing space. What it actually represents is something far more inventive: a fiscal manoeuvre disguised as trade policy.

Let’s strip the romance out of it.

Vehicle imports into Sri Lanka attract, on average, taxes and levies approaching 300% of the invoice value, payable in rupees. Customs duty. Excise. VAT. Port charges. Para-tariffs. Call it what you like — the end result is simple. For every dollar’s worth of vehicles imported, the government extracts roughly three dollars’ worth of rupees.

Which means this:

By permitting USD 1.7 billion in vehicle imports, the state is effectively selling dollars at a 300% premium over the official exchange rate — without calling it an exchange rate operation.

This is not monetary policy. It is creative liquidation.

A Dollar Sold Three Times

Consider the mechanics.

Importers surrender USD 1.7 billion to pay for vehicles. Those dollars either replenish reserves or cycle through authorised channels. In return, the Treasury collects a tsunami of rupees — far exceeding what it would receive through normal taxation.

This is not revenue in the conventional sense. It is forex-backed rupee extraction.

In plain terms: the government is monetising foreign exchange without printing money, without announcing a bond auction, and without submitting to the discipline of market-tested borrowing.

Which raises an uncomfortable question.

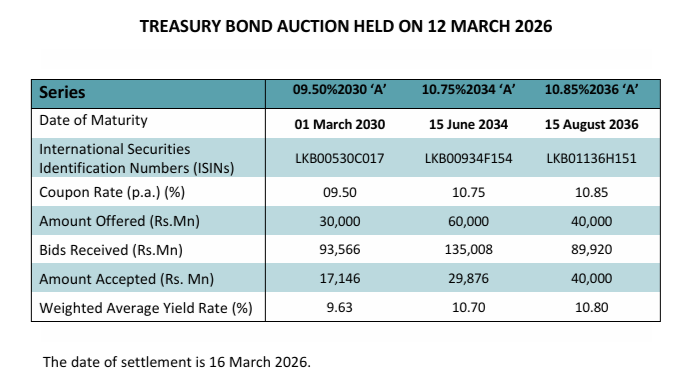

If the Treasury can vacuum up rupees this way, does it need to borrow as much via Treasury bills and bonds? The recent patterns suggest: not quite.

Borrowing Without the Headline

Domestic borrowing has not vanished. But the urgency has softened. Auction pressure has eased. Rates are less jumpy. And yet expenditure hasn’t exactly tightened its belt.

So where is the rupee liquidity coming from?

One possibility — whispered rather than admitted — is that state-owned banks are being leaned on more heavily, not through overt lending, but through balance-sheet gymnastics involving long-term funds.

Which brings us to the pension elephant in the room. The Pension Fund Question No One Answers

Sri Lanka’s two major state banks sit atop enormous pension and provident fund exposures — funds that are long-dated, politically invisible, and conveniently patient.

Are these funds being used, directly or indirectly, to absorb government paper?

Are maturities being rolled, yields adjusted, exposures concentrated?

Most importantly:

Have adequate provisions been made in the financial statements of these banks to reflect the real risk carried on behalf of pension contributors?

Silence.

The public is told that the system is sound. But, are there provisions made adequately to cover the liabilities including the pensions liability. That reserves are adequate. That debt is “manageable”. That confidence has returned.

Even in the calculations made, are the provisions in conformity with the assumption parameters to be applied in keeping with up to date standards?

Or is the situation leading to another repetition of what we witnessed in 1992 when the Finance Minister himself had to declare their insolvency.

Confidence is not an accounting standard.

What This Really Is

Let’s be clear. The vehicle import decision is not reckless. It is deliberate.

It accomplishes several things at once:

It injects consumer confidence.

It revives related sectors.

It generates massive rupee inflows without visible borrowing.

It allows the Treasury to postpone politically awkward bond auctions.

And it converts dollar scarcity into fiscal advantage.

From a narrow technocratic standpoint, it is clever. From a governance standpoint, it is evasive.

Because this is not reform. It is bridge financing disguised as liberalisation.

The Reserve Illusion

If reserves truly stand at USD 6.4 billion, then surrendering USD 1.7 billion to import vehicles should not be alarming. But reserves are not a pile of cash in a vault. They are layered, encumbered, and partially spoken for.

The real test is not the headline number. It is how quickly reserves are recycled to fund fiscal comfort.

A country rebuilding buffers does not rush to convert them into SUVs and hybrids — unless it needs the rupees more than the dollars.

The Question That Matters

So here is the question that should be asked — loudly, publicly, and repeatedly:

Is the government using import-driven tax windfalls to reduce transparent borrowing, while quietly shifting risk onto state banks and long-term funds?

If yes, where is the disclosure?

If no, where is the data?

Because if this is the new model — selling dollars at a 300% tax premium instead of issuing debt — then Sri Lanka has not escaped its fiscal habits.

It has merely changed the packaging.

Stability Is Not Reform (Again)

This looks stable. It feels stable. But stability achieved by asset drawdown and off-balance-sheet pressure is not durable. It is a pause — not a pivot.

True reform would mean:

Clear disclosure of reserve use,

Transparent domestic borrowing data,

Explicit safeguards for pension funds,

And honesty about how the state is financing itself.

Until then, let’s call this what it is.

Not recovery. Not reform.

Just Sri Lanka selling its dollars at a luxury mark-up — and hoping no one asks who’s paying the bill later.