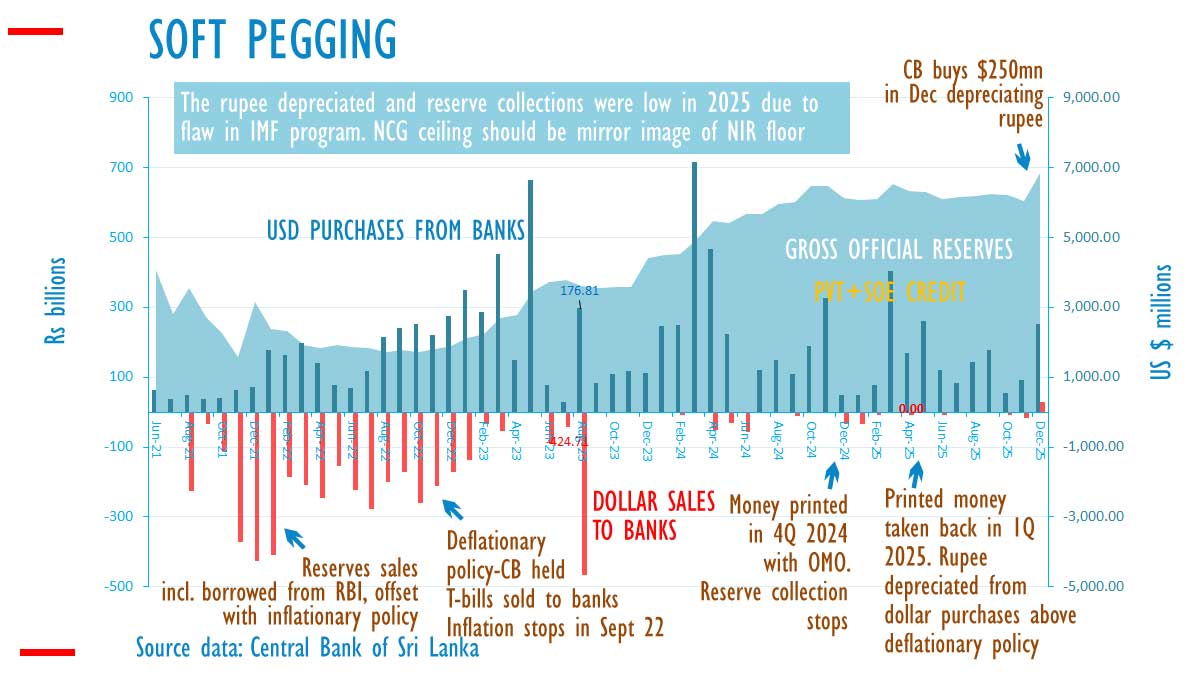

FINANCIAL CHRONICLE – In December 2025, Sri Lanka’s central bank purchased 250.8 million US dollars from the public, while selling back 28.3 million dollars, according to official data. This activity resulted in the depreciation of the rupee by nearly three rupees. By the end of the year, the rupee was trading just under 310 per US dollar in the spot market, with some moral suasion reportedly applied.

There is a prevailing narrative among macro-economists in Sri Lanka that the rupee is market-determined. However, the aggressive exchange rate policy, characterized by central bank purchases of dollars, suggests otherwise. Unlike private citizens or the Treasury, central bank purchases lead to the creation of new money, or what Governor John Exter referred to as the ‘monetization’ of a balance of payments surplus.

According to Bellwether, an economic columnist for EN, the central bank is ‘supremely unqualified’ to build reserves compared to the Treasury or individuals who save dollars privately. While Treasury purchases to repay debt or individual savings in foreign currency immediately curtail consumption and imports, central bank purchases inject new rupees into the economy, maintaining purchasing power.

A balance of payments surplus, which exerts upward pressure on the exchange rate, can occur if some liquidity created by the central bank’s monetization is extinguished through deflationary policy. The central bank receives coupons on its bond holdings from the Treasury, enabling an equivalent amount of dollars to be permanently kept as reserves. Any unwinding of buy-sell swaps could improve net reserves by replacing borrowed dollars with those purchased outright, provided the rupees are deflated and credit and imports are controlled.

If the central bank continues to buy dollars beyond the scope of its deflationary policy, the rupee depreciates. This practice has been termed the ‘Political Ravishment’ of the rupee.

The depreciation of the rupee occurred even amid record current account surpluses. Traditionally, macro-economists blame current account deficits, drawing on Mercantilist doctrine for currency issues, but in 2025, they lacked this excuse.

Historically, the central bank has created external challenges by maintaining low rates through inflationary policies, known as ‘rate cuts’, enforced via inflationary open market operations since February 1952. The central bank also attributed external difficulties to budget deficits from around the same time, thereby avoiding accountability for keeping rates low. Consequently, exchange and import controls were tightened on the populace.

The presence of exchange controls indicates that the central bank is unaccountable for its inflationist operating framework, which is fraught with anchor conflicts. The central bank ostensibly pursues an inflation-targeting framework with a domestic inflation index as the anchor, until inflation rises with credit growth, necessitating a clean float. Under such a float, no money is created through international operations, preventing reserves from being accumulated for government debt repayment or other purposes, while reserve money can be regulated through rate adjustments.

However, when the central bank purchases dollars to build reserves and interferes with the ‘floating’ exchange rate, creating new money, it effectively runs an externally anchored monetary regime. This conflicting anchor mix, described as a ‘flexible exchange rate’, allows central banks in developing countries to evade accountability when currencies depreciate. This narrative is prevalent not only in Sri Lanka but in all IMF-prone countries, suggesting that exchange rates are ‘market determined’.

Analysts argue that a central bank with an IMF reserve target cannot simultaneously pursue a domestic anchor and keep rates low without either missing targets or causing rupee depreciation, which could lead to increased energy and food prices, social unrest, and the ousting of democratically elected governments.

Currency depreciation not only disrupts family finances, leading to social unrest, but also affects state enterprises, particularly energy utilities, and the government budget. Rising energy prices make elected governments unpopular. Macro-economists, however, often exclude food and energy prices from inflation indices, printing more money and maintaining low rates, claiming that ‘core inflation’ remains stable. In January, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation raised prices despite easing global crude prices. Similarly, the Ceylon Electricity Board requested an 11 percent price hike, calculating with the rupee at 308 compared to around 303.

The concept of core inflation was devised by MIT academic Robert J. Gordon following the collapse of the Smithsonian Agreement, which disrupted commodity prices and led to what is now known as the Great Inflation.

In the last quarter of 2024, large-scale money printing was halted, and in 2025, the central bank operated under a scarce reserve regime, injecting money overnight at the ceiling policy rate of 8.25 percent, thus enabling interbank markets to function. In March 2025, the central bank purchased 400 million dollars, allowing the money printed in late 2024 to be extinguished in early 2025. Prime lending rates and some deposit rates moved to mobilize savings for credit, reducing the risk of a full-blown currency crisis and a second default typical in countries with soft-peg or flexible exchange rates.

Sri Lanka was also struck by Cyclone Ditwah in early December. Historically, natural disasters have helped strengthen the currency if credit growth slows. For instance, following the 2004 tsunami, private credit stalled in January 2005, aiding currency appreciation.

Flexible exchange rate regimes are vulnerable to severe confidence shocks, with importers covering early and exporters delaying when the currency declines. Banks also attempt to maintain their net open positions, which reduces imports unless inflationary open market operations accommodate them. When the currency stabilizes following a credit slowdown or disaster shock, the opposite occurs: importers delay coverage to secure better prices, exporters sell quickly, and banks reduce their NOPs.

Meanwhile, rising Treasury bill yields could also prevent imbalances and deter markets from malinvestments prompted by the so-called transmission mechanism. Previously, when public debt was under the Central Bank, large volumes of maturing debt were monetized rather than rolled over, leading to currency crises and blaming budgets. Higher Treasury bill yields can crowd out private credit and imports, helping avert further rupee collapses. (Colombo/Jan08/2026)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.