“no majority, however large, can outrun that truth”

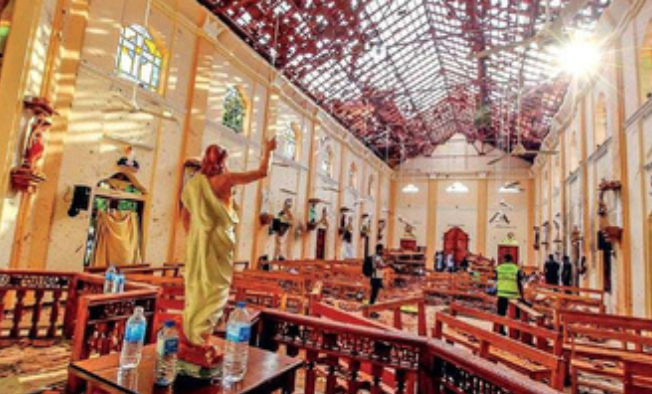

Nearly seven years after the Easter Sunday bombings tore through churches and hotels, killing more than 270 Sri Lankans and injuring nearly 500 others, the most uncomfortable truth is this: the problem is no longer a lack of evidence, but a lack of political will.

This is not a charge made lightly. It is a conclusion reached after watching successive governments promise closure, commission inquiries, reshuffle investigators, and speak solemnly at memorials—while the core questions remain conspicuously unanswered.

When the Channel 4 documentary aired just before the presidential election, it did more than revive public anger. It reset expectations. The incoming National People’s Power (NPP) government, campaigning on rupture and reform, undertook to bring swift resolution to what is arguably Sri Lanka’s gravest peacetime crime. The pledge was clear: truth, accountability, and justice—without fear or favour.

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake reinforced that promise in symbolism and substance. His visit to the Katuwapitiya church—where entire families were annihilated—was not perfunctory. It was deliberate. He spoke of justice, of answers, of the moral obligation owed to the dead and the living. For a country accustomed to rhetorical empathy followed by institutional paralysis, the moment carried weight.

Yet, months into a presidency backed by a 159-strong parliamentary majority, the silence is growing louder.

Rehiring Investigators, Reheating Hope

One of the early signals of intent was the re-engagement of senior investigators associated with earlier probes. Most notably, Shani Abeysekera—now Director of the Criminal Investigation Department —was restored to a position of strategic authority.

The optics were strong. So too was the implication: that dormant investigative threads would finally be pulled together.

What followed, however, has been procedural motion without prosecutorial momentum.

The uncomfortable fact is that much of what is still being “investigated” is already in the public domain. The Fundamental Rights application filed by Abeysekera himself contains extensive material: timelines, intelligence failures, ignored warnings, and circumstantial links that point not merely to negligence but to possible complicity or wilful blindness at the highest levels of the security apparatus.

This is where the gap between promise and performance becomes impossible to ignore.

The Intelligence Question That Will Not Go Away

No serious discussion of Easter accountability can avoid the name Major General Suresh Sallay, former head of military intelligence. Despite repeated public references, parliamentary interventions, and documented anomalies—including the now-infamous issue of a compromised passport—there has been no visible movement toward arrest, indictment, or even sustained public questioning.

Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka did not mince his words in Parliament, stating that for Sri Lanka’s “super spy” to obtain such a passport was “a matter accomplished over the telephone.” That remark was not rhetorical flourish; it was an indictment of how power functions in this country—quietly, efficiently, and beyond scrutiny.

Yet, despite this, and despite the fact that Sallay’s career trajectory accelerated during the Rajapaksa years, the post-election environment has produced no demonstrable accountability mechanism. Promotions have histories. Silence has consequences.

Why has the case of the former child soldier Pillayan’s release from charges of murder not being reinvestigated?

f this government can continuously attempt to charge Governor Cabraal on matters related to the Greek Bonds purchase despite a Supremne Court order on that – why cant the government launch an investigation into Pillayan’s release from remand on allegations of a murder of a politician? What uncomfortable truth are they afraid to unearth? And Why? It haunts me to remember the apparent dedication that AKD spoke in parliament about the Easter Bombings. Several times he made solemn assurances as President but every time he has fallen short. It is time AKD got hold of an efficient secretary. The penalty he will pay is being returned to his home where tranquility abounds but no electoral endorsement.

If the state is unwilling—or unable—to confront the intelligence establishment, then the promise of Easter justice was always conditional.

Why the Riots Didn’t Happen—and Why That Matters

In the immediate aftermath of the bombings, Sri Lanka stood on the brink of communal catastrophe. The anger was real, the fear weaponised, and the potential for retaliatory violence enormous— particularly in Muslim enclaves around Negombo.

That catastrophe did not occur for one reason alone: the intervention of Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith.

At a moment when silence or ambiguity would have been easier, the Cardinal spoke with moral clarity. He urged restraint. He stated, unequivocally, that Muslims are not terrorists. His voice—calm, courageous, and resolute—prevented what could have been a bloodbath. This was not merely religious leadership; it was statesmanship in its purest form.

It is one of the great ironies of the Easter aftermath that the strongest defence of social cohesion came not from the state, but from the Church—even as the Church continues to demand answers the state has failed to provide.

Power Without Progress

So why has an administration with unprecedented parliamentary strength failed to move decisively?

The reasons are not technical. They are political.

First, the Easter file intersects with institutions the Sri Lankan state has never fully subordinated to civilian oversight: intelligence, military hierarchies, and entrenched security networks. Any serious prosecution risks opening doors that many in power—past and present—would prefer remain closed.

Second, transitional governments often underestimate the inertia of the system they inherit. Replacing personalities does not dismantle cultures. Reassigning investigators does not guarantee prosecutorial independence if decision-making remains centrally constrained.

Third—and most uncomfortably—there is the fear of destabilisation. Easter accountability is not a single case; it is a thread. Pull it hard enough and it unravels narratives carefully constructed over years: about patriotism, counter-terrorism, and the selective use of intelligence.

The Cost of Delay

Every delay deepens mistrust. For the families of the dead, justice deferred is not an abstraction—it is daily trauma compounded by indifference. For the broader public, the lesson is corrosive: that even mass murder does not guarantee accountability if it implicates the powerful.

President Dissanayake came to office promising rupture. On Easter, rupture means this: naming failures, indicting perpetrators, and confronting the intelligence state without compromise.

Until that happens, the Easter bombings will remain what they have tragically become—not just a crime without closure, but a mirror held up to Sri Lanka’s enduring inability to hold power to account.

And no majority, however large, can outrun that truth.

Faraz Shauketaly – www.shauketaly.com (Farazcolombo@gmail.com)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.