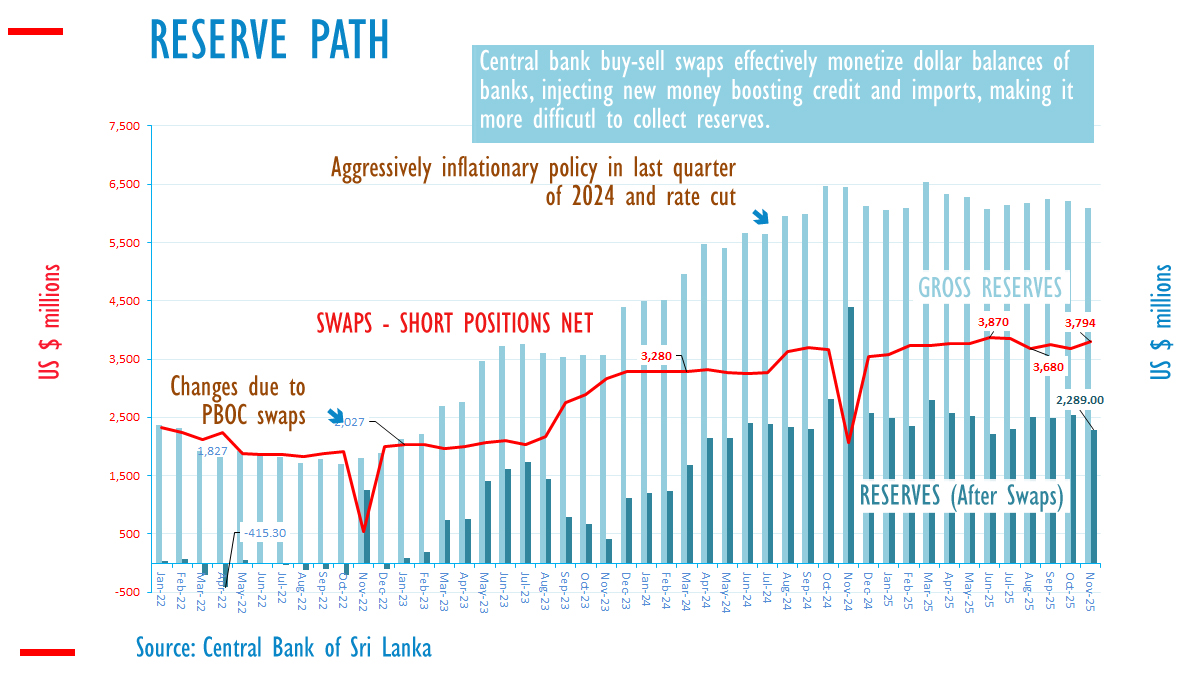

Sri Lanka’s central bank reported a decline in foreign exchange reserves, net of swaps, to USD 2,298 million in November 2025, down from USD 2,533 million in October. This reduction occurred before the impact of Cyclone Ditwah and the disbursement of a new emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), according to official data.

In January 2025, the reserves net of swaps stood at USD 2,482 million, while gross reserves remained largely unchanged. At the start of the year, the central bank’s swaps, including a non-inflationary one with the People’s Bank of China, amounted to USD 3,548 million. By November, buy-sell swaps had increased to USD 3,794 million.

The central bank’s buy-sell swaps are considered inflationary because they monetize the dollar balances of commercial banks, providing them with newly created local currency to extend credit and increase imports, while the foreign exchange risk is borne by a government agency.

Although the IMF program has imposed controls on sovereign guarantees for government credit, no limits have been set on the foreign exchange risk the central bank can assume. During the last currency crisis, following a surrender rule that led to a currency collapse, the central bank incurred a loss of LKR 700 billion due to its swaps.

The Committee of Public Finance in the Sri Lankan parliament has raised concerns about the practice of engaging in risky derivatives. Critics argue that in modern democracies, parliament is the only entity capable of regulating a central bank, albeit constrained by the principle of ‘instrument independence,’ a concept promoted by macro-economists during the inflationary era.

Historically, particularly in the UK, parliaments imposed operating frameworks on central banks, thus limiting their ability to suppress rates and create external economic issues. Sri Lanka’s central bank must accumulate reserves to repay its debts to India, which are linked to funds borrowed to maintain low rates during the last economic crisis, including through swaps.

To permanently accumulate reserves, a deflationary policy must be implemented, whereby rupees generated from foreign exchange purchases are extinguished. However, in 2025, deflationary policy was restricted to the coupons on the central bank’s restructured domestic bond stock.

In December, following the devastation of Hurricane Ditwah, the IMF provided an emergency loan of USD 206 million, marking the 18th loan by the institution to the country after the main program was delayed due to additional budget spending. Analysts had cautioned throughout the year that the reserve projections were compromised by a flaw in the IMF program’s quantitative targets, which did not mandate a reduction in central bank-held bonds.

Since the central bank creates money through dollar purchases—a process described by the agency’s founding Governor John Exter as the monetization of the balance of payments—this money eventually returns to foreign exchange markets as imports through the credit system. If the dollars were not returned, the currency would depreciate.

In 2025, the central bank allowed the currency to depreciate from approximately LKR 290 to LKR 310 against the US dollar. Unsterilized rupees from buy-sell swaps would exert similar pressure on the currency unless they were extinguished through an unsterilized sale of dollars. Some dollars were provided to the government in 2025 through unsterilized sales, preventing a further currency collapse.

Macro-economists have asserted that exchange rates are ‘market determined,’ but they are ultimately the outcome of the central bank’s operating framework. Exchange rates are purely the result of monetary policy in the case of floating exchange rates and a combination of monetary and exchange policies in the case of a soft-pegged or flexible exchange rate.

When monetary and exchange policies are in conflict, a currency will depreciate against another currency with a superior operating framework. Before the IMF’s Second Amendment, central banks were not allowed to avoid accountability by claiming money was ‘market determined.’

Economic analysts have pointed out that if money were market determined, like carrots or beans, an economy would revert to a primitive barter system. The entire concept of money is that it is not market determined; it serves as a unit of account, a store of wealth, and a standard of deferred payments.

The inflationist operating framework of the central bank has led to repeated currency crises since the end of the civil war, resulting in eventual default and reform reversals by previous governments, critics have stated. (Colombo/Jan17/2026)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.