Questioning the Answers

By Faraz Shauketaly

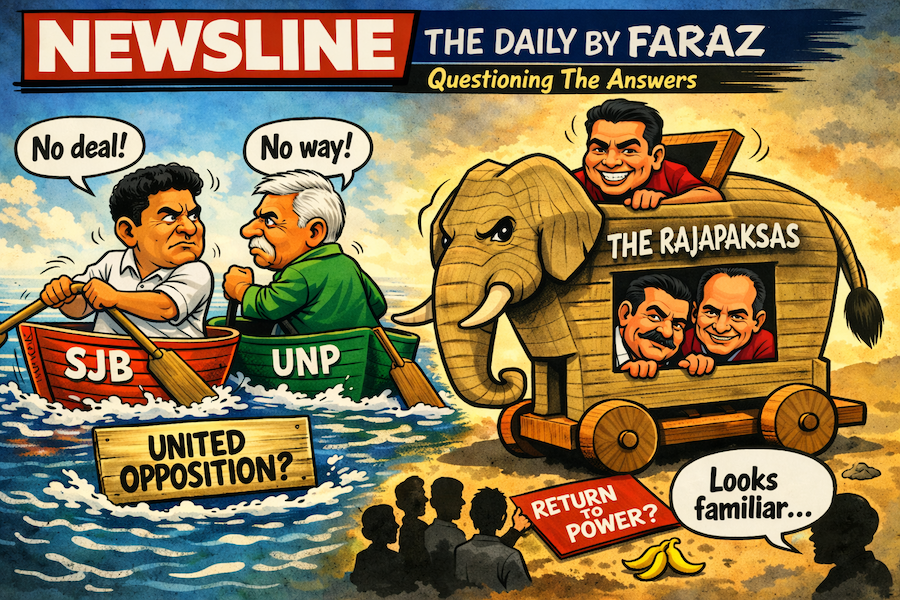

Sri Lanka’s opposition today resembles a reunion nobody planned, attended by people who insist they have moved on—but keep bumping into each other anyway. The question now hanging over the political landscape is deceptively simple: can the Samagi Jana Balawegaya and the United National Party find a way to coexist, cooperate, or even reunite—without rewriting history or repeating it?

And if they can’t, an even more uncomfortable possibility emerges: the vacuum will not remain empty. It will be filled. Almost certainly by a force Sri Lanka claims to have rejected—but never quite dismantled.

Let us start with the obvious irony. The SJB is, in many ways, the UNP’s ideological offspring. Most of its senior figures were once dyed-in-the-wool UNPers, complete with green credentials, reformist rhetoric, and a deep familiarity with internal party warfare. The split that produced the SJB was less a revolution than a family feud—one that replaced the old patriarch with a new standard-bearer, but never quite settled the inheritance.

Today, the SJB is led by Sajith Premadasa, the Leader of the Opposition, a man who has spent years trying to step out of both his father’s shadow and his party’s past. The UNP, meanwhile, remains firmly in the grip of Ranil Wickremesinghe—former President, serial Prime Minister, and the last man standing from a political era that refuses to exit the stage politely.

Between them lies an awkward truth: separately, neither looks capable of mounting a credible, sustained opposition to the government. Together, they might. But “might” is doing a great deal of work in that sentence.

The problem is not arithmetic. On paper, an SJB–UNP alignment makes sense.

It consolidates voter bases that already overlap, reduces fragmentation, and presents the electorate with something approaching coherence. The problem is psychological—and personal. Old wounds linger.

Old betrayals are remembered. And old leadership styles have not been forgotten, even if they are occasionally repackaged.

For the SJB, an alliance risks diluting its claim to being the “new opposition”. For the UNP, it risks admitting what many within it privately concede: that the party, on its own, no longer commands electoral gravity. For both leaders, it raises the delicate question of who leads, who follows, and who pretends not to notice.

And while this hesitation continues, time is not standing still.

If the SJB and UNP fail to form an effective opposition—whether through alliance, coordination, or at the very least disciplined cooperation—the space they leave behind will not be filled by silence. It will be filled by familiar populism, refurbished grievance, and a narrative that thrives on resentment rather than accountability.

Enter the Rajapaksas.

Much has been said about the family’s fall from grace, their electoral defeats, and their supposed political irrelevance. Yet Sri Lankan politics has a habit of resurrecting what it has not conclusively buried. The re-emergence of Namal Rajapaksa as the apparent standard-bearer of that political lineage may unsettle many—but it should not surprise anyone.

History suggests that when the centre fragments, the margins consolidate.

An ineffective opposition does not merely fail to check the government; it re-legitimises what the electorate thought it had rejected. If Sajith Premadasa and Ranil Wickremesinghe cannot find common cause, the argument that “at least the old order knew how to govern” will begin to sound persuasive to voters fatigued by instability and disappointment.

This is the real risk—not that the Rajapaksas return triumphantly, but that they return by default, as the only recognisable alternative left standing.

None of this requires ideological alignment between the SJB and the UNP. It requires something more basic: political adulthood. An acceptance that opposition is not a personal audition, but a collective responsibility. That leadership is not proven by dominance within one’s own party, but by the ability to organise resistance beyond it.

The electorate is not asking for miracles. It is asking for coherence, clarity, and a credible counterweight to power. Whether that counterweight is forged through alliance or coordination is secondary. What matters is that it exists—and soon.

Because if the current opposition continues to look inward, the country will look elsewhere. And history suggests that when Sri Lanka looks elsewhere in frustration, it often finds itself staring into a mirror it hoped never to see again.

The choice facing the opposition is stark, even if it pretends otherwise: unite enough to shape the future, or stay divided and inherit the past.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.