The Central Bank of Sri Lanka is poised to present a report detailing its achievement of maintaining inflation below 2 percent during the first and second quarters of 2025, despite not meeting its controversial 5 percent inflation floor, according to an official government statement.

The bank recorded an average inflation rate of -1.1 percent in the second quarter of 2025 and 0.8 percent in the third quarter, both figures falling below the stipulated floor rate of 2 percent, as outlined in a post-cabinet statement.

Kabir Hashim, an economist and member of the Committee on Public Finance, commended the central bank for its “exceptionally great” performance in delivering monetary stability, a rarity in the country, despite missing its 5 percent target.

Hashim, who previously served as a minister in a 2015 administration, witnessed the disruption of free trade policies due to liquidity injections via inflationary open market operations, termination of sell-buy swaps, initiation of buy-sell swaps, and outright bond purchases, which abandoned the “bills only” policy.

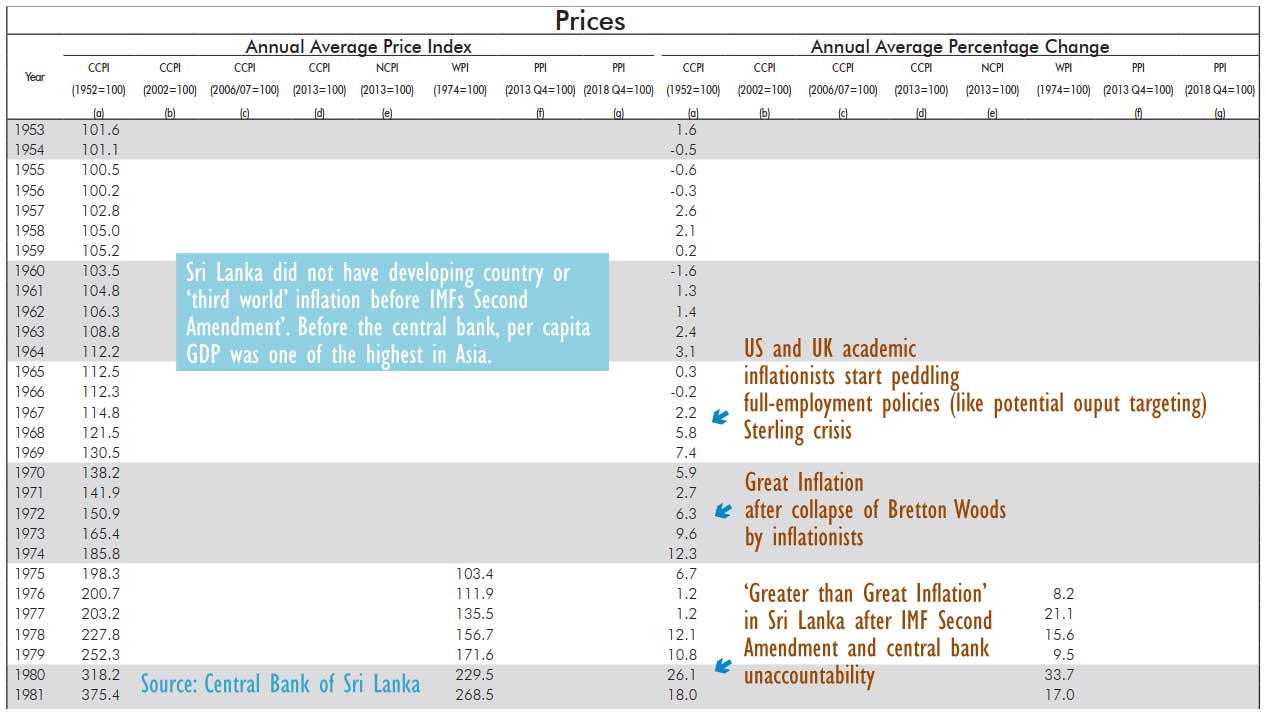

Historically, Sri Lanka’s inflation rates were comparable to those of developed countries until 1978. However, following the International Monetary Fund’s Second Amendment, the country’s inflation trajectory began to diverge, coinciding with rising social unrest.

The central bank had convinced then-President Ranil Wickremesinghe, who was ousted during a stabilization crisis, to establish a 5 percent inflation target as a floor rather than a ceiling—a decision that critics argue exacerbates accountability issues.

FC’s economics columnist Bellwether commented, “Modern macro-economists can mislead legislators with empirics, which is merely historical data. The dismissal of economic theory in favor of empirics has led to negative consequences globally. Unlike robust theory, empirics are unreliable for predicting future outcomes. Vector auto regression is not economics; it is merely statistics.”

Analysts are advocating for a revised central bank operating framework with a ceiling of 2 percent to prevent macro-economists from potentially leading the country toward a second default through rate cuts justified by a high inflation target.

In 2025, monetary policy was broadly deflationary, with the government paying interest coupons on a central bank-held restructured rupee bond stock, thereby reducing liquidity. The central bank has been praised for its performance, allowing current account surpluses by facilitating debt repayments, though its exchange rate policy has prompted some concerns.

(Colombo/Jan21/2026)