Sri Lanka has taken measures to prevent several multinational companies from establishing industries using coconut husks, aiming to protect local businesses that are less efficient, according to Plantation and Community Infrastructure Minister K V Samantha Vidyaratna.

The disclosure came during a parliamentary session following a complaint by Sujeewa Dissanayake, a member of parliament from the Kurunegala district representing the National People’s Power. Dissanayake noted that multinational companies in the Wariyapola and Panduwasnuwara areas were offering higher prices to coconut farmers for husks.

With the growing demand for coconut husks, which are increasingly used for moisture retention and as a growth medium, local industries that produce coconut fibre products have struggled to compete. These local businesses, which operate using simpler methods, face challenges against larger, more technologically advanced firms.

“With the entry of large factories, competition has intensified,” Minister Vidyaratna stated in parliament. “By November 2025, the price of a coconut husk rose to around 22 rupees in some regions. This situation makes it difficult for some local industries to remain viable. Where technology and mechanization are more advanced, profitability is achievable. However, to protect smaller local companies, we did not approve the foreign investors.”

In a 2026 budget address, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake expressed the goal of driving Sri Lanka’s economic growth to 8 percent annually. Nonetheless, analysts argue that growth cannot be achieved by resisting change, promoting low-tech industries, or deterring foreign investments, which would prevent farmers from earning higher prices for raw materials.

Sri Lanka is also a known exporter of coir fibre pith (cocopeat), bristle fibre, and mattress fibre, which are utilized as growth mediums.

By safeguarding local industrialists through protectionist measures, Sri Lanka risks discouraging coconut farming by preventing higher prices for husks. This policy reduces revenue and profits available to coconut farmers, which could lead to a decline in coconut farming.

Meanwhile, many coconut landowners in the traditional Coconut Triangle are selling their land for residential development in response to the lack of profitability in coconut farming. Minister Vidyaratna mentioned plans to enhance farms through a ‘cluster system’ with state intervention.

“To control land division, we have established a special board within our ministry. Without its approval, land splitting is not permitted,” Vidyaratna explained. “We are enforcing laws in this regard.”

As Kurunegala rapidly urbanizes with industrial and residential development, coconut landowners are moving away from farming. By preventing land from being utilized optimally and maintaining the status quo, Sri Lanka could hinder economic output and freehold land rights, which are crucial for growth and prosperity.

In a move towards increased protectionism, Sri Lanka recently banned the import of tinned fish, surpassing the import taxes of the Rajapaksa era. Critics argue that the rent-seeking tinned fish sector, along with maize autarky and rice taxes, has driven up protein prices, contributing to malnutrition among children in poorer families. Import taxes and licensing on foods like maize have a long history of corruption involving regional and national politics.

Minister Vidyaratne noted that the cost of producing coconut fibre has increased, as coconut husk chips have become a growing global industry. The Coconut Development Authority has also requested control over husk cutting, though other agencies are promoting the activity, which has been identified as a ‘problem.’

Sri Lanka is working to boost coconut production by expanding land and enhancing productivity through infilling and replanting. In 2024, the country produced 2.7 billion coconuts, with plans to increase this to 4.2 billion by 2030 through fertilizer subsidies.

According to the Coconut Research Institute, the average yield per coconut tree in Sri Lanka is 55 nuts annually. “That is insufficient,” Minister Vidyaratna stated. “In India, the yield is 80 nuts per tree, while in Malaysia and the Philippines, it is 120 nuts per tree.”

There are plans to expand coconut cultivation in the North to 40,000 hectares by 2027, with a budget allocation of 600 million for the Northern Coconut Triangle. An additional 500,000 trees are being distributed to home gardens.

Approximately 900 coconut-based industries are registered with the Coconut Development Authority. A subsidy of 30,000 rupees per acre is available for those implementing irrigation systems that adhere to proper standards.

As of 2024, Sri Lanka had 484,677 hectares under cultivation, according to data from the Coconut Research Institute and Coconut Development Board, based on Census Department figures. The country is home to 65 million coconut trees.

Sri Lanka’s exports of coconut products, including activated carbon, coconut milk, bristle fibre, coconut ice cream, and coconut oil, reached 1.127 billion US dollars by November 2025. “We expect total exports to have grown to 1.25 billion in 2025,” Minister Vidyaratna said. In 2017, coconut exports were valued at 598 million dollars, which increased to 855 million by 2024.

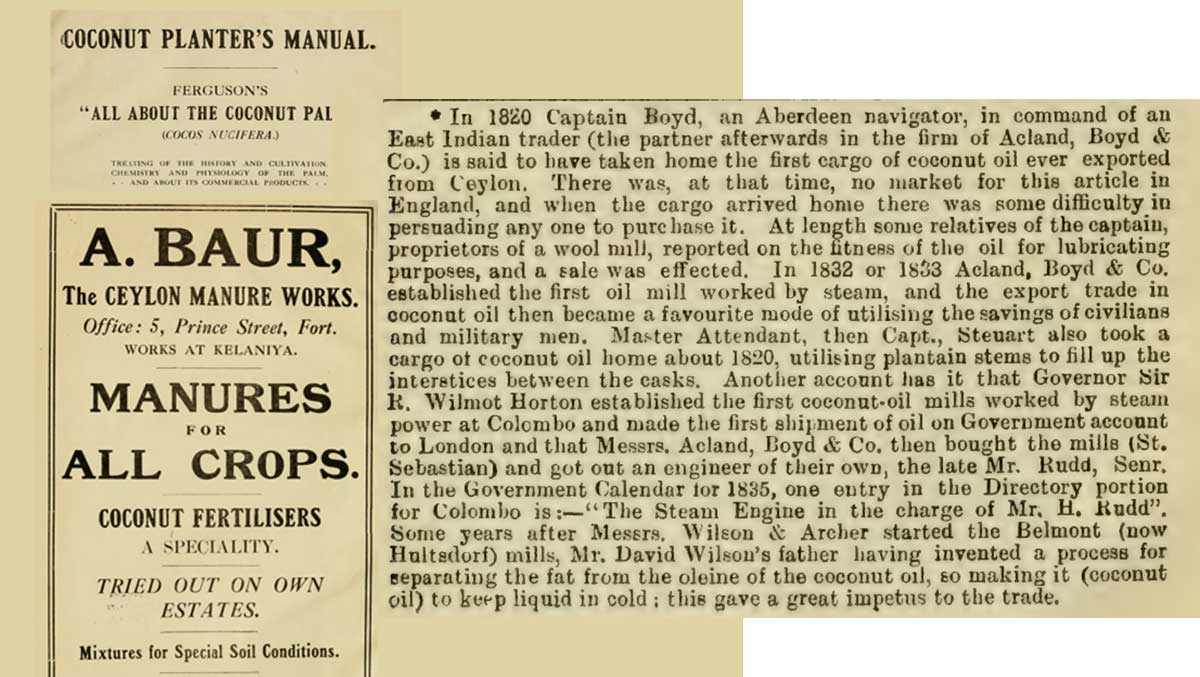

Coconut cultivation expanded significantly during British rule, extending beyond the fibre exportation seen during the Dutch period.