The Central Bank has done what it often does in moments of uncertainty: hold the line. Policy rates remain unchanged at 7.75%, as the country moves through another critical stretch of IMF programme review politics—where the numbers must behave, the messaging must be calm, and everyone pretends the economy is a spreadsheet instead of a household.

On the IMF front, there’s renewed attention because Sri Lanka could receive a sizeable disbursement if reviews align—reminding us again that in the post-default era, cashflow is not a budget issue, it is a geopolitical weather system. Economy watchers are fixated on what comes next: credit ratings, market access ambitions, and the fragile credibility built since the 2022 crash.

Rates staying put is not a “non-event.” It’s a signal: the Central Bank is prioritising stability and inflation expectations, especially as demand strengthens and core inflation risks creeping up. For business, this is both reassuring and irritating. Reassuring because policy isn’t swinging wildly. Irritating because borrowing costs don’t magically become friendly just because the macro headlines are less dramatic than they were in 2022.

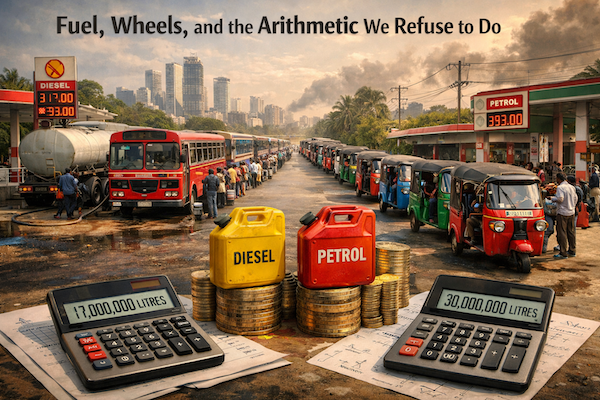

And then there’s the public mood. People aren’t living inside “policy corridors”; they’re living inside grocery bills. A rate decision is felt indirectly—through credit costs, job creation (or its absence), and how quickly wages catch up to real prices. Stability is valuable, but stability that never translates into household relief becomes a political problem for any government, regardless of party colour.

The uncomfortable truth: Sri Lanka is still in the era of “macro compliance.” Every decision is filtered through programme targets, reviews, and international confidence. That isn’t necessarily bad—discipline matters after a collapse—but it does mean domestic policy has limited room for populist shortcuts, even if they’re tempting.

So yes, we may get IMF money. Yes, the rate stays at 7.75%. But the real question for NEWSLINE readers is simpler: does this stability become felt stability?

If the answer stays “not yet” for too long, the public will conclude what it always concludes: that reforms happen on paper, and pain happens at home.