When Family Stewardship Becomes a Glass Ceiling

“Let families own. Let professionals run. Let markets judge.”

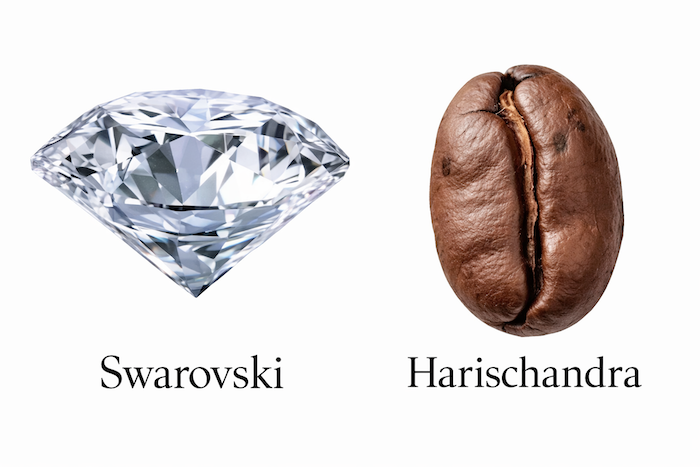

For more than a century, Swarovski perfected the art of making brilliance look effortless. Precision-cut crystal, global cachet, and a brand that became shorthand for affordable luxury. From chandeliers to couture, the sparkle travelled far.

What didn’t travel as smoothly was governance.

The uncomfortable question hovering over Swarovski’s recent history is not whether it survived as a family business — it did — but whether family control quietly constrained the company’s full commercial potential at precisely the moment global luxury became faster, harsher, and less sentimental.

Swarovski A Dynasty Built on Precision

Founded in 1895 in Austria, Swarovski thrived on technical excellence and obsessive quality control. For decades, family ownership aligned perfectly with brand guardianship. The crystals dazzled; the balance sheet followed.

Then the market changed.

Luxury polarised. Fast fashion accelerated. Direct-to-consumer went digital. Competitors professionalised leadership, sharpened portfolios, and ruthlessly exited underperforming lines. Swarovski, meanwhile, remained family-managed deep into the 21st century, with overlapping roles, competing branches, and boardroom tensions that reportedly slowed decisive action.

This was not incompetence. It was over-stewardship.

Family control preserved identity — but also preserved indecision.

Control vs Growth: The Cost of Consensus

By the late 2010s, Swarovski was feeling pressure:

- Rising costs in Europe

- Eroding mid-market luxury margins

- Strategic drift between fashion, jewellery, B2B crystal supply, and décor

Professional managers were brought in, but without full authority. Strategy requires speed; family governance requires harmony. When the two clash, markets punish hesitation.

Eventually, reality intervened. Swarovski began restructuring, slimming operations, refocusing the brand, and — crucially — reducing direct family control over day-to-day management.

The company didn’t lose its soul.

It regained momentum.

A Sri Lankan Parallel: Harischandra Mills

The story has a familiar ring closer to home.

Harischandra Mills is one of Sri Lanka’s most recognisable heritage brands — trusted, conservative, and culturally embedded. Like Swarovski, it benefited enormously from family stewardship: consistency, integrity, and resistance to reckless expansion.

But also like Swarovski, critics have long asked whether professional management, innovation, and scale were delayed by excessive familial caution.

No scandal. No collapse. Just opportunity cost.

In both cases, the question is not whether family owners cared — they cared deeply — but whether respect for legacy became a substitute for strategy.

Sentiment Is Not a Strategy

Family businesses often confuse three very different ideas:

- Ownership – a right

- Stewardship – a responsibility

- Management – a skill

The first two do not automatically confer the third.

Swarovski’s late pivot suggests a hard-earned lesson:

you can honour the founder without managing like one forever.

Harischandra’s challenge — still unresolved (work in progress) — is similar. The brand’s potential extends beyond tradition. The market will not wait politely while families decide.

when cut cleanly — not when handled too gently.

The Verdict

Did the Swarovski family destroy value? No.

Did they delay value creation? Almost certainly.

Family ownership saved the brand from reckless short-termism.

Family control, held too long, slowed adaptation.

The healthiest model is not abandonment of heritage — it is separation of affection from execution. And when one considers a Trillion rupee business, that is not petty cash.

Crystal, after all, is strongest