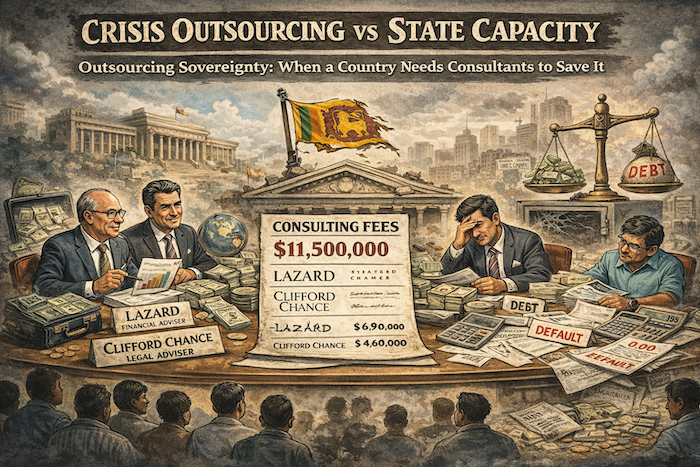

Outsourcing Sovereignty: When a Country Needs Consultants to Save It

Sri Lanka did not just default in 2022. It revealed something more uncomfortable: when the crisis arrived, the State could not negotiate its own survival without renting global expertise.

So the Government hired Lazard as financial adviser and Clifford Chance as legal adviser for external debt restructuring — via a Cabinet-approved procurement process, reportedly selecting from dozens of proposals. The reported fees: about US$6.9 million to Lazard and US$4.6 million to Clifford Chance — roughly US$11.5 million in all.

To some, this is scandalous: “Why should a poor country pay millions to foreign firms?”

To others, it is obvious: “If you’re bleeding out, you don’t haggle with the surgeon.”

Both instincts are understandable. But the bigger question is not the invoice. The bigger question is what the invoice says about the Republic.

A sovereign state is meant to be able to do three things under pressure:

count its money, negotiate its liabilities, and defend the public interest.

In 2022, Sri Lanka struggled with all three.

Advisers Aren’t the Problem — Dependency Is

Let’s be precise. A restructuring adviser does not govern a country. An adviser models the debt stock, tests scenarios against IMF targets, helps structure offers, and supports engagement with creditor groups. The State decides; the adviser advises.

So the existence of advisers is not, by itself, evidence of wrongdoing. It is evidence of something else: capacity gaps.

The public can accept hiring expertise when it is used to build competence. What the public cannot accept — and what it increasingly suspects — is a state that hires experts as a substitute for competence, then forgets everything once the crisis quietens.

The Real Test: What Did We Buy?

The public wants a simple answer: What did US$11.5 million buy?

Not vague assurances. Not conference slides. Not “ongoing discussions.”

The deliverable Sri Lanka actually needed was measurable:

debt relief large enough to restore sustainability,

a path to restore market access without repeating the same sins,

and credibility that the country wouldn’t relapse the moment the pressure eased.

Here’s the hard truth: advisers can help design the bridge, but they cannot force politicians to cross it. They cannot impose discipline. They cannot manufacture trust when governance continues to wobble.

If the State is inconsistent, advisers become expensive witnesses to indecision.

Procurement Was Competitive — But Accountability Must Be Too

We are told the selection followed a competitive process, with many proposals considered and Cabinet approval granted. Fine. That answers “was it a tender?” at a high level.

But citizens deserve more than procurement hygiene. They deserve outcome transparency.

If millions can be paid, then the public should see:

the scope of work (what was contracted),

the milestones (what was delivered, when),

and the performance measures (how the advice improved the result).

Otherwise, “competitive procurement” becomes a procedural fig leaf — and the trust deficit deepens.

The Uncomfortable Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s debt crisis was not just an economic event. It was an institutional audit — and the State failed key sections.

If we want Independence to mean something more than flags, we must treat the crisis as a lesson, not an episode.

The real reform is not to shout at advisers. The real reform is to ensure that, next time, the Republic has:

a permanent sovereign debt office with top-tier talent, transparent debt reporting,

a culture of early warning rather than late panic,

and political costs for those who gamble with national solvency.

Because if we do not build state capacity, we will repeat the cycle:

mismanage collapse hire foreigners patch up forget repeat.

That is not sovereignty. That is subscription.

And no country should have to pay a recurring fee to remain afloat.