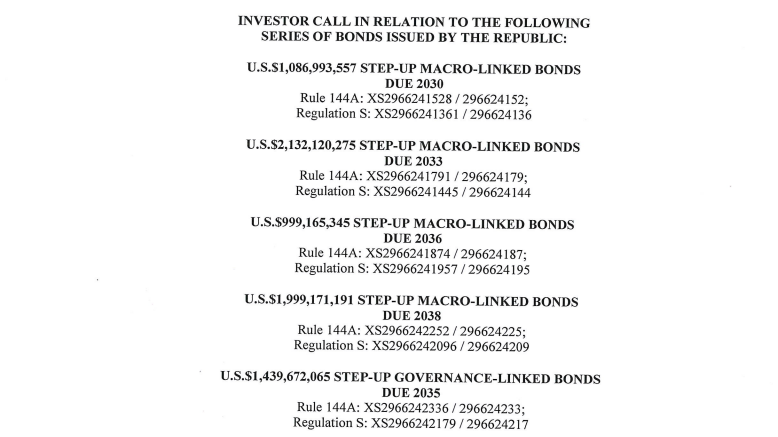

Mihin Lanka did not fail because Sri Lanka couldn’t run a low-cost airline.

It failed because Sri Lanka tried to run one without following the rules of low-cost aviation—or the rules of governance.

Low-cost carriers succeed on three boring but brutal disciplines: cost control, independence, and volume-driven pricing. Mihin Lanka had none of the three—yet had plenty of something else: political sponsorship.

First, the conception was political, not commercial. Mihin Lanka was launched with the promise of affordable travel and national pride, but without a credible business plan that respected LCC economics. Aircraft were leased at unfavourable rates. Routes were chosen for optics rather than yield. Decisions answered to ministries, not markets. Airlines don’t survive applause; they survive spreadsheets.

Second, cost discipline was absent from day one. True low-cost carriers sweat every rupee—single aircraft types, fast turnarounds, lean staffing, ruthless route profitability. Mihin Lanka, meanwhile, inherited legacy behaviours without legacy revenue. It was a budget airline in branding, but a full-service airline in habits—and that combination is fatal.

Third, it was under-capitalised and over-promised. Losses mounted quickly, but instead of restructuring early, the airline limped along on state support. Delayed payments, accumulated debt, and vendor pressure became routine. An airline bleeding cash cannot wait for tourism growth or political goodwill to rescue it.

Fourth, competition was misread. Mihin Lanka was supposed to complement SriLankan Airlines, but in practice it duplicated routes, cannibalised demand, and added complexity. Two state-backed airlines chasing the same limited market is not competition—it’s self-harm.

Fifth, governance was weak. Boards changed. Strategies shifted. Accountability dissolved. No successful airline is run like a revolving-door committee. When losses are socialised and consequences diluted, discipline evaporates.

So was timing to blame? Partly. Fuel prices fluctuated. Tourism cycles were uneven. But other low-cost carriers across Asia faced the same headwinds—and survived— because they were insulated from political interference and anchored to commercial reality.

The final act was inevitable. Mihin Lanka was absorbed into SriLankan Airlines, its debts quietly transferred, its experiment concluded without a post-mortem worthy of the cost to the taxpayer.

The lesson is uncomfortable but essential: Airlines are businesses first, symbols second.

You cannot run an airline to create jobs, please voters, reward loyalty, or signal ambition. You run it to fill seats profitably, every day, on every route, without excuses.

Until Sri Lanka accepts that commercial enterprises— especially airlines—must be governed commercially or not at all, Mihin Lanka will remain what it ultimately became:

A case study in how politics, when it tries to fly, usually crashes the balance sheet first.