FINANCIAL CHRONICLE – Sri Lanka’s state finances are witnessing a positive trend as citizens’ incomes approach levels seen before the crisis. However, the newly secured International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan underscores vulnerabilities in the country’s flexible inflation targeting and exchange rate regime.

Looking ahead to 2026, Sri Lanka may face challenges due to potential inflationary policies by the Federal Reserve and the implications of a rate cut in May. This analysis was conducted in late December and appears in the January 2026 issue of Echelon Magazine.

The recent IMF loans, post-Ditwah, echo the Active Liability Management law from the Yahapalana era, when foreign borrowings were used to repay maturing debt rather than stabilizing monetary policy to pay off debt with current inflows.

Under the leadership of Sri Lanka’s central bank, the currency’s appreciation from 300 to 360 against the US dollar and stabilization around 300 has provided a foundation for non-inflationary growth, helping citizens recover and sustain themselves. Nevertheless, the rupee’s depreciation, particularly after the May rate cut, highlights the risks associated with a flexible exchange rate.

Fragility: Thin Default Margin

In July, this column warned that the May rate cut increased the risk of default by reducing the buffer needed to repay debt. This “buffer” consists not of past reserves but the ability to collect dollars through interest rate structures.

“Recent central bank policies have weakened Sri Lanka’s defense against potential defaults, with the recent rate cut occurring as deposit rates were on the rise,” this column cautioned in July. “Inflationary open market operations could lead to zero reserve accumulation and diminished foreign exchange collections, penalizing savings.”

The column repeatedly cautioned that reserve targets might not be met if rate cuts are based on historical inflation data rather than classical economic principles. The IMF has since adjusted its reserve targets, although the central bank has been amassing net reserves.

The External Financing Gap and Interest Rates

The 18th IMF program, which includes a $200 million Rapid Finance Instrument as an emergency loan, has exposed the fragility of Sri Lanka’s capacity to repay loans at current interest rates. The IMF’s “external financing gap” is not determined solely by payment obligations but is exacerbated by low credit rates that boost domestic credit and imports while reducing the ability to accumulate dollars for debt repayment.

IMF loans and additional budget support loans may delay necessary interest rate corrections, maintaining high import levels. This mirrors the Yahapalana period, where foreign debt surged due to rate cuts for flexible inflation targeting, unsettling foreign investors.

Fragility: Rupee Depreciation from Arbitrary Interventions

The current monetary framework’s fragility is further exposed by the flexible exchange rate, characterized by ad hoc interventions to accumulate reserves while denying convertibility when newly created rupees turn into imports. This regime has led to rupee depreciation without direct inflationary policies, except for the monetization of a balance of payments surplus.

The rupee depreciated from 290 to 310 against the US dollar over 2025. Continued depreciation is possible if the central bank purchases dollars above the deflationary policy from its bond portfolio. This depreciation stems from exchange rate policy errors, diverging from classical economics.

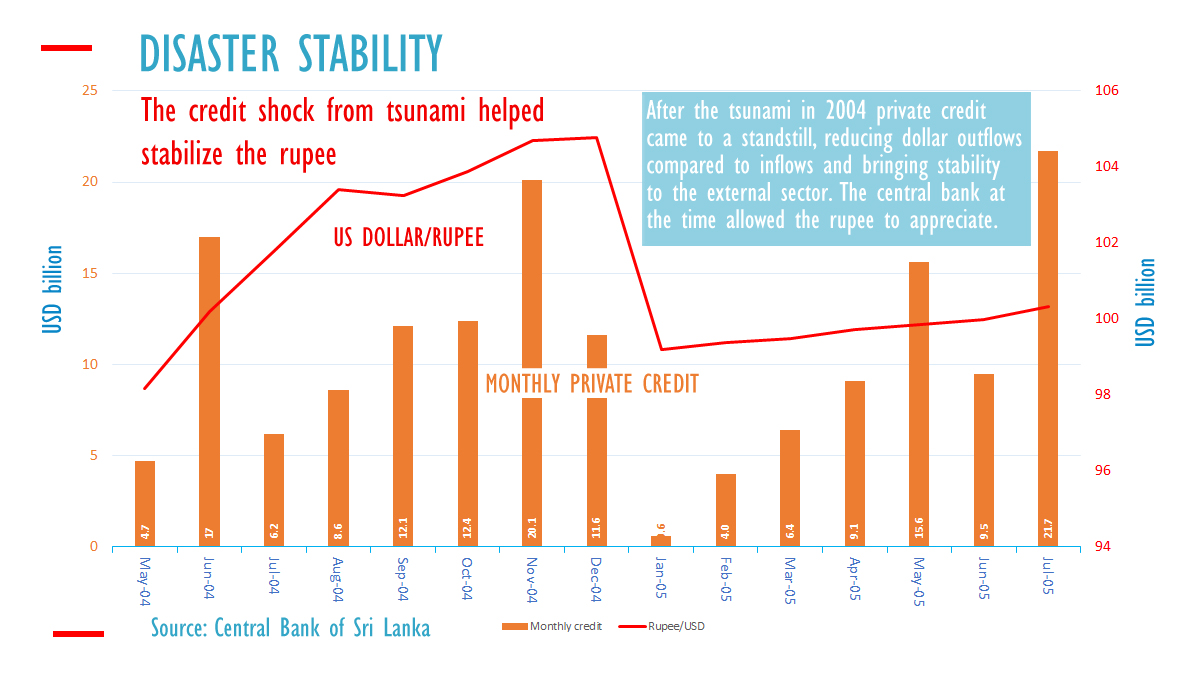

Ultimately, monetary and exchange rate policy errors impact the exchange rate and balance of payments. In 2004, monetary policy errors led to a steep rupee depreciation, halted in January after the tsunami brought a credit shock that stabilized the rupee.

Graph HEADLINE: Disaster Stability

SUBHEAD: The credit shock from the tsunami helped stabilize the rupee

Private credit, easing in December, collapsed in the following months, with consumption and investment taking time to recover.

The Ditwah cyclone, while not as psychologically impacting as the tsunami, has displaced 1.7 to 2 million people, delaying their return to normal consumption patterns. Vehicle importers report collapsed sales, and an immediate credit shock is likely, easing as reconstruction begins.

Sweeping Subsidies

Unlike in 2004, the government is providing extensive relief payments to Ditwah victims, funded by an overextended domestic “buffer.” However, these domestic buffers deposited in banks may be re-loaned, potentially disrupting the banking system and stressing interest rates. Liquidity injections to suppress rate spikes could destabilize the external sector and exchange rate.

The government should avoid creating an economic crisis from disaster relief, as the central bank’s operating framework is weak and rates are already low. Further depreciation will not aid Ditwah victims or those still struggling from the 2022 currency collapse.

The notion that exchange rates are “market determined” is misleading, allowing macro-economists to avoid accountability for flawed policies. Exchange rates result from monetary policy, whether through clean floating rates, hard pegs, or arbitrary actions in flexible regimes.

External Headwinds

The possibility of a renewed commodity bubble from the Federal Reserve could destabilize the global economy. Since March 2022, the Fed has pursued deflationary policy, including rate hikes, but has now ceased quantity tightening amid rising inflation, maintaining high liquidity levels.

The Fed’s evolving framework since the 2008 housing bubble has led to various bubbles in crypto, gold, and stocks, while ordinary people face inflation. Nationalists are gaining ground in Europe amid inflation and instability, raising concerns of conflict.

Unlike historical conflicts, Sri Lanka lacks a robust monetary regime to protect the economy. The IMF program triggered by Cyclone Ditwah underscores the urgent balance of payments needs, estimated at $720 million.

The Thirst for Inflationary Policy

Despite calls for rate cuts in response to Trump tariffs, such actions could lead to a swift unraveling of the external sector and another default. Without deflationary policy, the Treasury cannot rely on the central bank to repay debt.

The central bank’s inability to collect reserves under a flexible exchange rate underscores the need for a pegged rate. If the rupee continues to depreciate, particularly amid a potential Fed-induced commodity bubble, political consequences could follow.

Given the 5 percent inflation target and 2025’s depreciation, the Treasury should urgently secure its own dollar sources and consider taxing in foreign currencies. The Treasury’s dependence on the central bank for reserves should end, ensuring dollar revenues are collected directly.

Removing legal impediments to the Treasury’s dollar transactions and tax collection is crucial, especially with amortizing sovereign bonds. Addressing the root causes of currency crises and excessive foreign borrowing is essential for long-term stability.