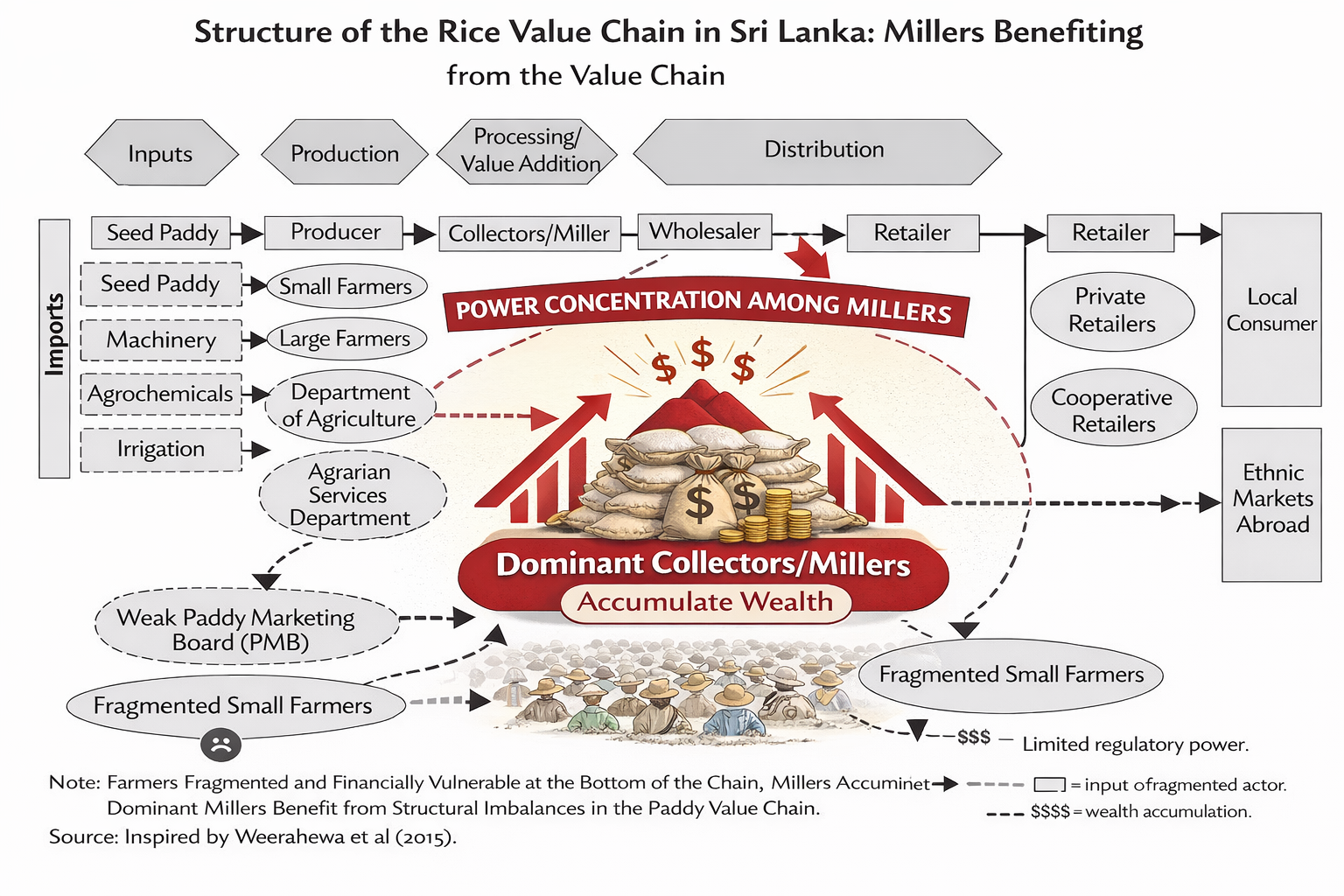

Sri Lanka’s rice economy is once again under intense public scrutiny, as critics allege that structural imbalances in the paddy value chain have allowed a handful of dominant millers to accumulate extraordinary wealth while small farmers remain financially vulnerable.

For decades, the Paddy Marketing Board (PMB), established in 1970, functioned as the stabilizing force in the rice market. It was mandated to purchase paddy, maintain buffer stocks, mill grain and distribute rice, thereby protecting farmers from price collapses and shielding consumers from extreme volatility. Although the PMB was abolished in the early 1990s and later re-established in 2005, resuming purchases in 2008, it no longer holds the commanding position it once did. Its storage capacity and financial firepower are limited compared to the scale of national production.

In the space created by the weakening of state dominance, large private millers expanded aggressively. Over time, the rice value chain became highly concentrated at the milling stage. While production remains fragmented among hundreds of thousands of small farmers and retail distribution is widely dispersed, the transformation of paddy into rice along with large-scale storage is controlled by a small number of powerful operators.

That concentration is now at the center of controversy.

During peak harvest seasons, when supply is abundant and farmers urgently need cash to settle debts and cover input costs, paddy prices typically fall. Large millers, equipped with significant warehouse capacity, purchase vast quantities. Months later, when market supply tightens and stocks are released gradually, retail prices often rise sharply. The recurring cycle has fueled allegations that the system allows value to be extracted at the expense of both producers and consumers.

Farmer representatives argue that the widening gap between farmgate and retail prices reflects structural imbalance rather than mere market fluctuation. “We carry the risk in the field, but others capture the margins,” said a farmer leader from the North Central Province.

Public anger has intensified as prominent industry figures, including well-known miller Dudley Sirisena, have been widely associated with conspicuous displays of wealth. Luxury vehicles, expansive assets and even private helicopters have become symbols in political rhetoric and social media commentary. For many struggling farmers facing rising fertilizer, fuel and labour costs, such visible prosperity has become a flashpoint.

There is no suggestion that wealth accumulation itself is illegal. Large millers operate licensed businesses and invest heavily in infrastructure, logistics and distribution networks that are critical to national food supply. However, critics argue that the scale of wealth concentration in a protected domestic market raises uncomfortable questions about pricing power and fairness.

Sri Lanka is not globally competitive in rice exports due to high production costs and limited international demand for the short-grain varieties preferred domestically. Exports mainly serve Sri Lankan communities abroad. As a result, the domestic market is effectively the primary arena of operation. In such a protected environment, where imports are tightly managed and competition is restricted, concentration at the processing stage carries amplified influence.

The PMB, though active, lacks the scale to consistently dictate price floors or counterbalance dominant millers. Its buffer stock operations are constrained by fiscal realities and logistical limitations. Former officials privately acknowledge that the Board now responds to market movements more often than it shapes them.

The term “Rice Mafia” has entered political vocabulary, though economists caution that the issue is structural rather than conspiratorial. When thousands of fragmented producers sell to a handful of powerful buyers who control storage and processing, bargaining power inevitably shifts. The imbalance becomes embedded in the system itself.

Rice is more than a commodity in Sri Lanka. It underpins rural livelihoods, national food security and political stability. When farmers remain indebted despite good harvests and consumers face periodic price spikes, trust in the system erodes. The visible contrast between rural hardship and urban displays of wealth has sharpened the debate.

Proposals for reform include expanding state storage capacity, enabling farmer-owned milling cooperatives, improving access to warehouse credit and increasing transparency in national stock disclosures. Whether such measures will be implemented remains uncertain.

For now, Sri Lanka’s rice economy stands as a case study in how control over a single node in a value chain can tilt an entire system. The paddy field may produce the grain, but power lies where it is stored, milled and released. In that imbalance lies the heart of the controversy.