Following a historic electoral victory, Sri Lanka’s National People’s Power (NPP) government came to power with an electrifying promise: “system change.” At the heart of this pledge lies “Clean Sri Lanka” (CSL), a flagship program touted as the operational arm of a new social contract grounded in anti-corruption, transparency, and the rule of law1 . As it rolls into a new year with an expanded budget of Rs. 6,500 million for 2026, a critical examination reveals a complex and contradictory reality. While CSL demonstrates political will and delivers visible environmental projects, its effectiveness as a tool to dismantle deep-rooted corruption is being hampered by a strategic overreach and unaddressed systemic flaws.

Despite these efforts, a deep analytical look uncovers fundamental contradictions between the program’s stated ambition and its practical execution, potentially diluting its core anti-corruption mission.

A Critical Analysis: The Contradictions of Scope and Substance

At the institutional level, the government has taken steps to strengthen the legal arsenal. It has continued the implementation of the Anti-Corruption Act of 2023 and passed the Proceeds of Crime Act in 2025, aimed at recovering illicit assets. Furthermore, symbolic actions, such as arresting former President Ranil Wickremesinghe for alleged misuse of public funds, were intended to signal that the era of elite impunity was over.

The government has backed its rhetoric with significant financial commitment. The program’s budget increased from Rs. 5,000 million in 2025 to Rs. 6,500 million in 2026, funding dozens of projects across social, ethical, and environmental “pillars”2. These range from beach conservation and waste management to food safety and road safety awareness campaigns2 4.

The NPP’s ascent to power was directly fueled by public fury over the 2022 economic collapse, an event widely attributed to decades of graft, cronyism, and patronage politics1 . The CSL program was conceived as the tangible response to this demand for accountability. It is framed not as a simple beautification campaign but as a comprehensive initiative to foster ethical and environmental consciousness.

The Promise: Ambitious Goals and Financial Commitment

Following a historic electoral victory, Sri Lanka’s National People’s Power (NPP) government came to power with an electrifying promise: “system change.” At the heart of this pledge lies “Clean Sri Lanka” (CSL), a flagship program touted as the operational arm of a new social contract grounded in anti-corruption, transparency, and the rule of law . As it rolls into a new year with an expanded budget of Rs. 6,500 million for 2026, a critical examination reveals a complex and contradictory reality. While CSL demonstrates political will and delivers visible environmental projects, its effectiveness as a tool to dismantle deep-rooted corruption is being hampered by a strategic overreach and unaddressed systemic flaws

A Critical Analysis: The Contradictions of Scope and Substance

Despite these efforts, a deep analytical look uncovers fundamental contradictions between the program’s stated ambition and its practical execution, potentially diluting its core anti-corruption mission.

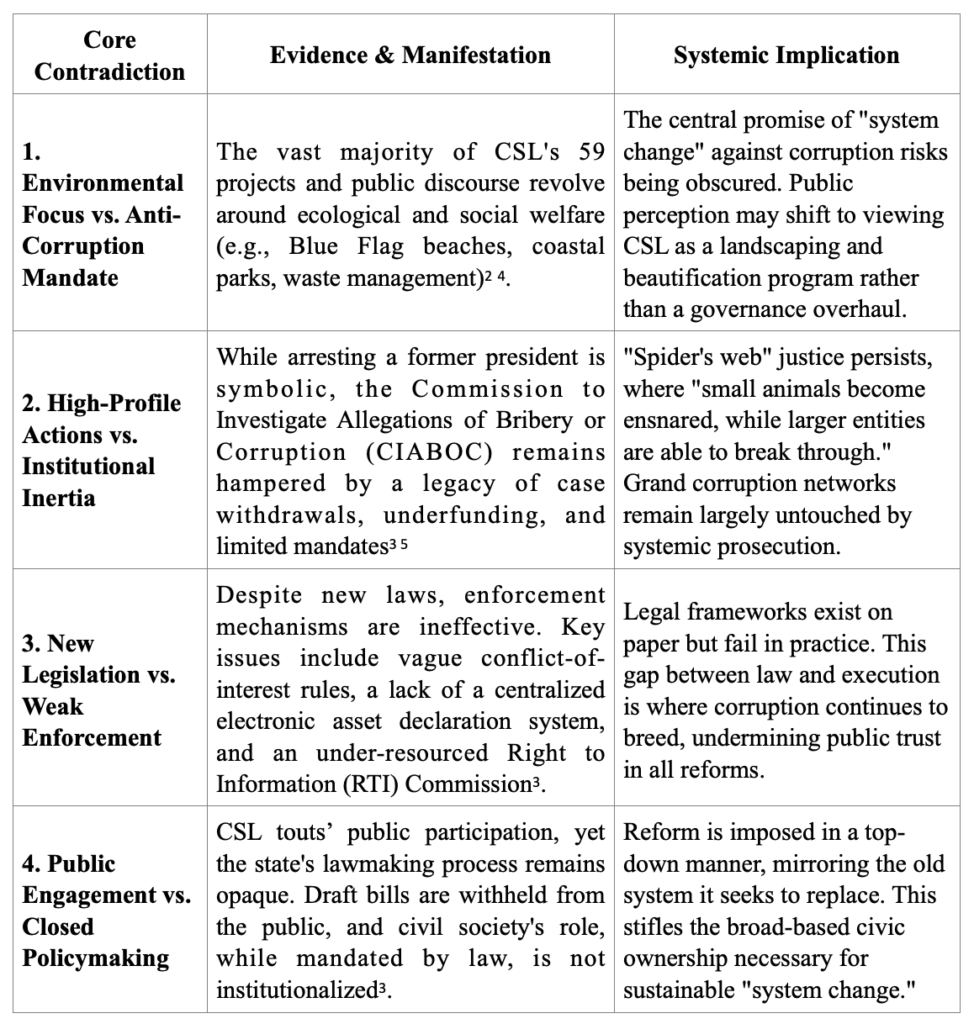

The table below outlines the core contradictions within the Clean Sri Lanka program’s implementation:

These contradictions point to a program struggling to define its core identity. A June 2025 civil society report by Transparency International Sri Lanka supports this critique, noting that despite progress in laws, Sri Lanka’s anti-corruption framework suffers from “weak implementation” and “persistent structural weaknesses”3. The CSL program, in its current form, does not appear to be a focused vehicle for rectifying these profound institutional deficiencies.

Charting a New Path: Targeted Solutions and Clear Implementation

For “Clean Sri Lanka” to become the transformative instrument it aspires to be, a strategic recalibration is urgently needed. The goal must shift from managing a wide portfolio of projects to surgically dismantling the architecture of corruption. Here are implementable solutions:

1. Refocus CSL’s Mandate and Metrics

- Solution: Legally redefine CSL’s primary Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) around institutional anti-corruption outcomes, not just environmental outputs.

- Implementation:

- Phase 1 (0-6 months): Amend the CSL framework to mandate that over 60% of its budget and reporting be dedicated to governance-strengthening projects.

- Phase 2 (6-18 months): Publicly track and report on metrics like the value of assets recovered under the Proceeds of Crime Act, the percentage reduction in CIABOC case withdrawals, and the number of high-ranking officials prosecuted.

2. Empower and Insulate Anti-Corruption Institutions

- Solution: Transform CIABOC from a politically vulnerable body into an independent, well-resourced powerhouse.

- Implementation:

- Legislative Action: Amend the Anti-Corruption Act to establish a transparent, multi-stakeholder (including civil society) panel for appointing the CIABOC Director General, with security of tenure3.

- Operational Boost: Direct a significant portion of CSL’s 2026 budget to CIABOC for three priorities:

1) Establishing the centralized electronic asset declaration system with public access, as repeatedly recommended3.

2) Creating a specialized Financial Crimes and Digital Forensics Unit. 3) Implementing nationwide witness protection programs.

- Legislative Action: Amend the Anti-Corruption Act to establish a transparent, multi-stakeholder (including civil society) panel for appointing the CIABOC Director General, with security of tenure3.

3. Enforce Transparency in Lawmaking and Political Finance

- Solution: Use CSL as a platform to enforce existing transparency laws and close critical loopholes.

- Implementation:

- CSL Transparency Portal: Launch a mandatory online portal under CSL where all draft legislation must be published for public comment at least 60 days before parliamentary debate3.

- Political Finance Enforcement: Task a CSL-monitored unit within the Election Commission with real-time auditing of campaign finances under the 2023 Election Expenditure Act. CSL’s public awareness campaigns should shift focus to educating citizens on how to track political donations and expenditure.

4. Build a Cross-Society Integrity Coalition

- Solution: Move from state-led action to a networked model of accountability.

- Implementation:

- Formalize CSL Partnerships: Legally incorporate credible civil society organizations, independent media groups, and business chambers into CSL’s oversight structure as non-governmental monitors.

- “Integrity Pact” Initiative: Use the CSL brand to promote and monitor “Integrity Pacts” in all high-value public procurement projects, where bidders and government agencies commit to transparency, with oversight by independent civil society observers.

For a Deeper Dive: Key Anti-Corruption Reforms Needed

The CSL program must be connected to broader, specific legislative and institutional reforms to be effective. Key priorities identified by analysts include:

- Judicial & Prosecutorial Independence: Creating an independent prosecutor’s office separate from the Attorney General’s Department to eliminate conflicts of interest in prosecuting state-linked corruption3.

- Beneficial Ownership Registry: Establishing a publicly accessible registry to reveal the true owners of companies, a critical tool against money laundering currently missing3.

- Strengthening the RTI Act: Imposing mandatory penalties on public authorities that unlawfully deny information requests to give the Right to Information law real teeth3.

Conclusion

The “Clean Sri Lanka” program is at a crossroads. Its current trajectory, laden with worthy yet peripheral projects, risks creating a paradox: a “clean” country of beautiful beaches and managed waste that remains fundamentally corrupt in its governance and economics. The immense political capital and public trust invested in the NPP’s promise of “system change” cannot be squandered on a diluted agenda.

True transformation requires the courage to narrow the focus, confront powerful vested interests, and fix the broken institutions that enable corruption. By refocusing CSL on its core governance mandate, the government can transition from performing change to delivering it. The choice is between creating a legacy of superficial cleanliness or forging a foundation of genuine integrity. For a nation that has endured the catastrophic costs of corruption, only the latter will suffice.

By Afflli Raheem:

The writer is a seasoned operations director, consultant, and writer, equipped with a diverse range of experience across fields such as business management, education, consultancy, and journalism. Send your queries to : afflli.raheem@gmail.com

1 https://www.ifri.org/en/studies/sri-lankas-npp-government-system-change-structural-compliance

2 https://cleansrilanka.gov.lk/blog/rs-6-500-million-allocated-for-expanded-clean-sri-lanka-efforts-in-2026

3 https://uncaccoaliEon.org/uncacparallelreportsrilanka/

4 https://www.presidentsoffice.gov.lk/special-media-release-on-the-clean-sri-lanka-programme/

5 https://eastasiaforum.org/2025/12/26/naEonal-peoples-power-moves-to-combat-corrupEon-in-sri-lanka/