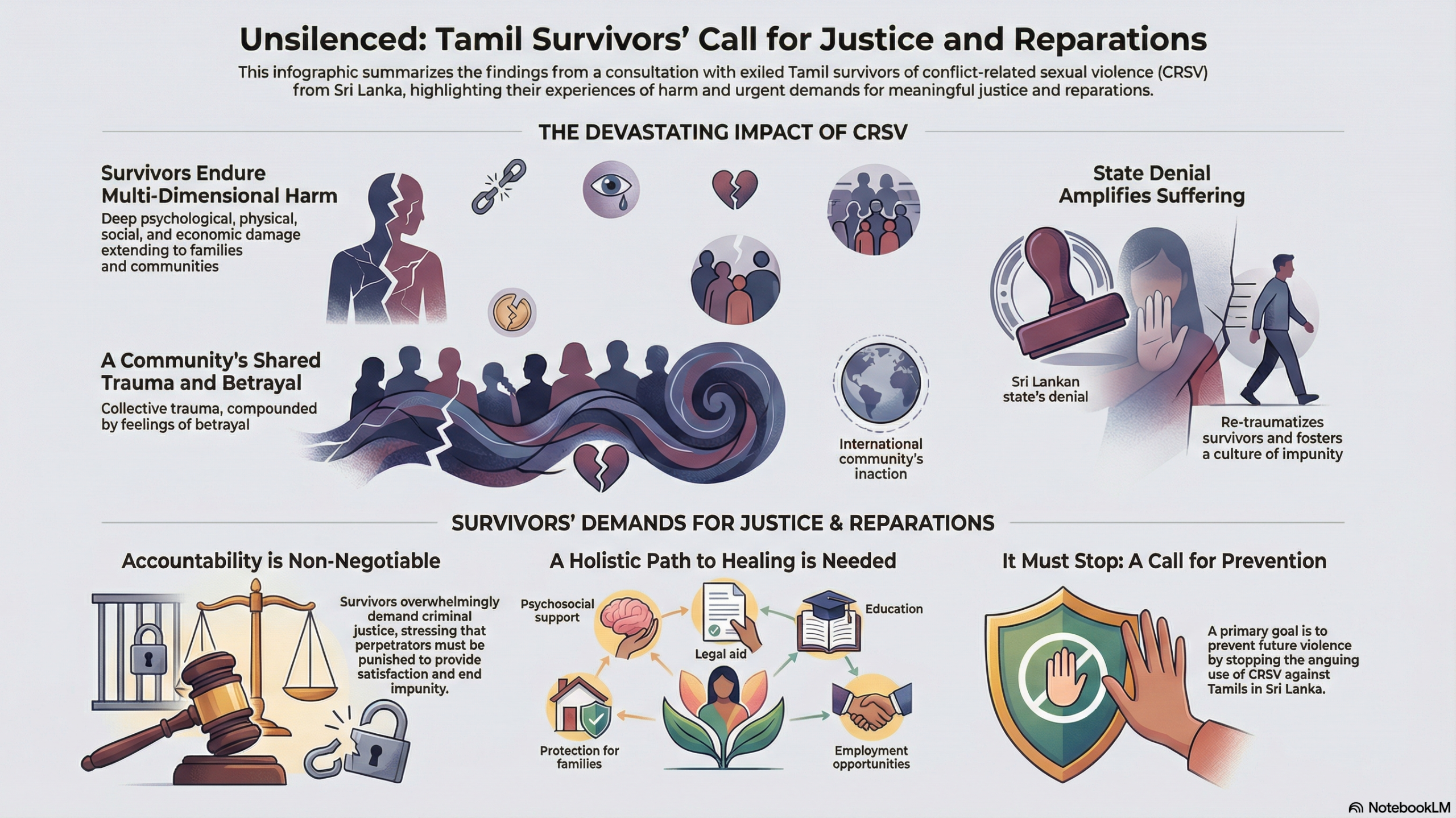

More than 16 years after the end of Sri Lanka’s civil war in 2009, Tamil survivors of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) living in exile in the United Kingdom continue to endure significant trauma that affects families and communities, according to a report by the International Truth and Justice Project (ITJP). The report highlights the ongoing physical, psychological, and social challenges faced by survivors, who have yet to receive acknowledgment, justice, or reparations from the Sri Lankan government.

The report, titled “Justice and Reparations Needs of Exiled Tamil Sri Lankan Survivors of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence,” draws from consultations with exiled Tamils and calls for urgent international intervention. It underscores the failure of the Sri Lankan government to address past atrocities and the need for healing.

Survivors of CRSV, who suffered from rape, gang rape, sexual torture, and humiliation by Sri Lankan security forces, continue to experience both physical and emotional scars. One male participant illustrated his isolation with a drawing of a figure “totally isolated from people, not able to live like a normal person.”

Physical repercussions include chronic pain resulting from injuries such as anal rape. One survivor expressed concern about ongoing health issues, stating, “We continue to have problems in our body after sexual violence – it is hard to pass stools in the morning – there is pain – we worry we might have this problem forever.”

Women reported assaults on breasts, causing lingering tenderness, while cigarette burns on visible areas like upper arms serve as constant reminders, particularly when wearing traditional saris. During the 26-year civil war (1983–2009) between government forces and the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), sexual violence against Tamils was systematic and deliberate, primarily perpetrated by state security forces as a tool of intimidation and control.

Documented acts included rape, gang rape, sexual torture, genital mutilation, forced nudity, and other humiliations, targeting Tamil civilians, detainees, militants, and prisoners of war—both women and men, including children—in detention centers, checkpoints, and militarized zones. The violence peaked during the war’s final phase in 2009, with mass rapes and sexual slavery amid the displacement of hundreds of thousands. It persisted post-war in the north and east, where a heavy military presence fostered impunity.

Human rights groups, including the UN and Human Rights Watch, have described these acts as potential war crimes and crimes against humanity, disproportionately affecting Tamils perceived as LTTE supporters. Male victims are often overlooked due to stigma. Survivors report long-term physical injuries, psychological trauma, social ostracism, and economic hardship, with abuse linked to broader ethnic repression.

Past Sri Lankan governments and the military have consistently denied or minimized allegations of sexual violence during the civil war, framing them as isolated incidents or fabrications by the Tamil diaspora. Despite calls for accountability from the UN and international organizations, credible investigations or prosecutions have not been conducted.

Successive administrations, including those led by former Presidents Mahinda Rajapaksa and Gotabaya Rajapaksa, have stalled transitional justice mechanisms, rejected international involvement, and maintained impunity for security forces. The current government under President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has pledged to address “controversial crimes” and restore the rule of law, yet as of early 2026, no tangible progress has been made on reparations or holding perpetrators accountable.

Psychological wounds manifest as stress, fear, suicidal thoughts, “deadly nightmares,” insomnia, and a pervasive sense of powerlessness. One survivor recounted memories of sexual violence in army-controlled areas, stating, “I am unable to forget or get rid of this for many years.”

The trauma extends to families, with survivors facing stigma, guilt, and denial of rights. One father shared how his son discovered his scars and questioned why he didn’t fight back, causing deep emotional pain.

Survivors also report social exclusion and threats from the army, including detention and surveillance. “Even approaching the Human Rights Commission yields no proper documentation or action, amid ongoing militarization in the north that restricts free movement,” survivors said.

Economic hardship is another consequence, with survivors facing employment discrimination. “If you are victims of sexual violence in Sri Lanka, people refuse to give you employment,” one survivor explained, adding that they are sometimes forced to accept undesirable work.

Impacts on children and marriages are also significant. Survivors struggle with intimacy and fear of sexually transmitted diseases as a result of the violence. Successive Sri Lankan governments have accused Tamil survivors and diaspora members of fabricating allegations to secure asylum or discredit the state, portraying such claims as propaganda or motivated by financial gain.

The report highlights collective trauma among Tamils, rooted in perceived betrayal by the international community and their own leaders. “We were betrayed at the end of the war by the UN and other international organizations,” one participant noted, expressing frustration and disillusionment.

Survivors call for independent international mechanisms to address their grievances and ensure perpetrators are held accountable. Without transformative reparations addressing stigma and structural inequalities, healing remains impossible, the report warns.

“Sexual violence is happening not only for women but also for men. More victims are in our home country than here,” another survivor added, emphasizing the need for an environment where survivors can speak openly. (Colombo/January 17/2026)