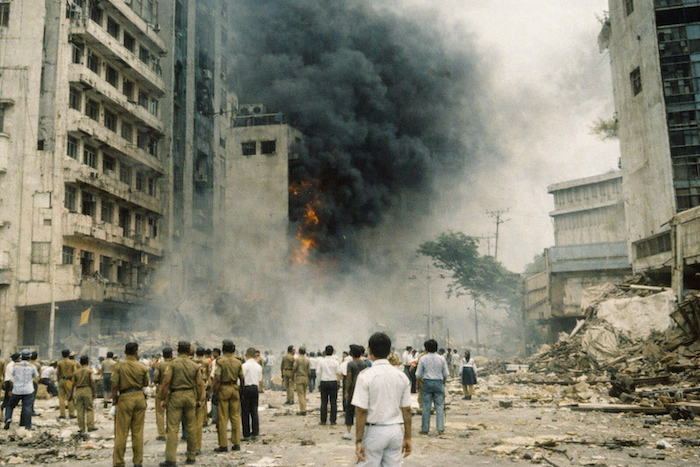

CBSL marked the 30th anniversary of the 1996 bombing.

As Sri Lanka marks the 30th anniversary of the 1996 Central Bank bombing, an uncomfortable symmetry hangs over the commemorations. The institution mourning a physical attack that killed 41 of its own now stands as the formal author of a far larger catastrophe: the country’s first sovereign bankruptcy.

The governor leading the memorials, Nandalal Weerasinghe, is also the official who announced to the world in 2022 that Sri Lanka could no longer pay its bills.

History will note the irony.

The 1996 bomb was unmistakable. It tore through concrete, killed civilians, injured hundreds and left Colombo’s financial district in ruins. The damage was immediate, measurable and, eventually, repairable. Buildings were rebuilt. Systems resumed. The dead were mourned, but the state endured.

The bankruptcy was different. It arrived without smoke or rubble, but its blast radius was wider and its effects more durable. Inflation wiped out savings. The currency collapsed. Fuel, food and medicine disappeared. Millions slipped into poverty. Hundreds of thousands left the country. Trust in public institutions — already thin — eroded further.

One bomb destroyed a building. The other dismantled an economy.

Weerasinghe may not have been in the CBSL in the final run-up to the announcement of bankruptcy, but as a deputy governor from 2011 to 2020, he was at the centre of the policies that led Sri Lanka to insolvency,

It was of course claimed by some that it was Ajith Nivard Cabraal’s defence of an artificial exchange rate and depletion of reserves by paying off ISBs, and Basil Rajapaksa’s fiscal choices of tax cuts without funding and borrowing without buffers, that led to the announcement of bankruptcy. However, the classic exchange rate policy in times of extreme shock – like a global economic crisis or a global health crisis (such as a pandemic) is the maintenance of a stable exchange rate, which is what Cabraal did. Also, when Gotabaya Rajapakse assumed the Presidency, the country’s growth had turned negative of 0.2%. In such a scenario, the textbook response is to reduce taxes and stimulate the economy. That was what was done and – strikingly – the law to reduce taxes were passed by Parliament without division – meaning it was unanimous.

From 2015 to 2019, under President Maithripala Sirisena and PM Ranil Wickremasinghe, together with Governor Indrajit Coomaraswamy, GDP growth plunged from 7.4% in 2014 to minus 0.2% in 2019. No development work of significance was seen during this period. The actual public Debt went up by 75%. Debt to GDP ratio rose from 69% to 84%. The Government borrowed US$ 12 billion from the International Sovereign Bond market. They allowed foreign exchange to be taken out of the country freely under the new Foreign Exchange Act in 2016. They sold the Forex Reserves to facilitate unnecessary imports which led to the reduction of the Forex Reserves to just US$ 7.6 billion at end-2019, from US$ 8.2 billion at end-2014.

As soon as President Gotabaya Rajapaksa assumed office in late-2019, he had to face the Covid Pandemic and the fall-out of the 2019 Easter Sunday terror attack. However, his Government, through Basil and Cabraal, was able to raise US$ 4.9 bn from bi-lateral sources and up to March 2022, and pay off or roll over all maturing debts, and bankruptcy was never considered even while the economic pundits screamed for a debt default. They also arranged a pipeline of new inflows of US$ 10.7 bn over the 12 months from April 2022 onwards but strangely, those inflows were not pursued after the departure of Basil and Cabraal, and a bankruptcy was hurriedly announced. The LKR was also kept steady throughout GR’s first two difficult years in office by Governors Lakshman and Cabraal but the Sri Lankan Rupee was floated at the latter stages of GR’s term at the insistence of the IMF and because of public outcries. GR’s Government also resisted an IMF programme that heaped burdens on people, but the strong IMF lobby wanted its invasion into Sri Lanka, and GR had to give in. But now, the same people who wanted the IMF, realize that the IMF has drastically impoverished the people in less than 2 years.

From April 2022 onwards, after the Bankruptcy was announced without even obtaining Parliament approval, and Sri Lanka defaulted on all foreign payments to bi-lateral and commercial lenders, all investors have withdrawn from the country, and no one has wanted to invest in Sri Lanka. All overseas funding lines and foreign-funded projects have stopped, leading to massive losses being suffered by those who were involved in those activities. The construction and the manufacturing industry have been seriously affected as none of the Letters of Credit from the Sri Lankan Banks have been recognized abroad due to the default situation.

The Governments of both Ranil Wickremesinghe and Anura Kumara Dissanayake have now made claims that the foreign debt has been re-structured successfully with extensive “hair-cuts” of the outstanding amounts. However, initial analysis shows that the overall effect of the re-structuring has been that no beneficial outcome has been achieved. Only the hapless EPF members have borne the brunt of the restructuring and lost about 47% of their savings. In the meantime, nearly 250,000 SMEs have gone out of business over the past 3 years, with more than 1 million people being rendered unemployed. The cost of living has become unbearable with fuel and other utilities being at highly excessive prices, and out of reach for most people, which means the majority of people have had to curtail their life-styles significantly.

Bankruptcy is never a policy choice; it is the absence of choices left. The claim that there was no option but to announce a bankruptcy is an absolute canard.

Technocracy is not absolution. By formally declaring bankruptcy and imposing the arithmetic of adjustment — floating the currency, hiking rates, locking the country into IMF conditionality — the Central Bank transformed accumulated policy failure into lived reality. Inflation became policy. As has happened in many countries, Austerity became unavoidable. Economic confidence was lost for decades. Political collapse followed.

Supporters argue there was no alternative. That is true — but only because alternatives were exhausted earlier or overlooked later. Bankruptcy is never a policy choice; it is the absence of choices left. The claim that there was no option but to announce a bankruptcy is an absolute canard.

The Central Bank bombing was an external act of terror. The bankruptcy was internal, cumulative and institutional.

One was inflicted on the country. The other emerged from within it.

Sri Lanka remembers the 1996 blast as a national tragedy. Future generations may remember the 2022 bankruptcy as something worse — not because it killed instantly, but because it permanently lowered the country’s economic ceiling. Physical bombs scar cities. Financial collapse scars societies — and lasts far longer.