Sri Lanka has never suffered from a shortage of businessmen.

What it has struggled to produce consistently are builders — individuals who begin with a discipline, master systems, and scale without mistaking visibility for value.

Nahil Wijesuriya belongs to that narrower, less glamorous category. His story is not one of overnight success, political theatre, or speculative bravado. It is a story shaped by engineering logic, operational patience, and incremental credibility — qualities that rarely trend, but often endure.

From Engineering to Enterprise

Wijesuriya’s professional formation matters because it explains much of what followed. A qualified Marine Engineer, he began his professional journey in 1964 as a Marine Engineering Apprentice at Walker Sons Ltd., and through dedication and expertise, rose to become the Chief Engineer of Colombo Dockyard in 1977. He sailed with vessels of the British Shipping Company, P&O Lines, and the Ceylon Shipping Corporation, serving as sailing Chief Engineer on all the ships, including as the first local Chief Engineer of the largest tanker, MT Tammanna.

Trained in a technical discipline before commercial pursuits, his grounding was precise and unforgiving: systems either work or they fail. That mindset — problem-solving over posturing — became a defining trait of his later entrepreneurship.

Unlike many who enter business through finance or family capital, Wijesuriya’s early professional years were shaped by hands-on exposure to operations, logistics, and process. It is a background that rewards discipline and punishes shortcuts — an education particularly well suited to Sri Lanka’s most challenging sectors.

Building from the Bottom of the Stack: Logistics

Wijesuriya’s entrepreneurial journey is closely associated with the East–West Group, which he founded and developed over time.

While his later ventures expanded into technology and media, the group’s origins were firmly in clearing, forwarding, and haulage — the invisible infrastructure that keeps trade moving.

This foundation is revealing. Logistics is not a sector one enters casually. Margins are tight, execution is everything, and reputations are built slowly. It demands systems, compliance, and an ability to deliver repeatedly under pressure. In an economy often disrupted by policy shifts, port congestion, and regulatory inconsistency, building a logistics business that survives — let alone grows — is itself a marker of competence.

From these

demonstrated a talent for spotting and scaling opportunities. He leveraged the discipline, process orientation, and operational rigor honed in logistics to expand into other sectors, including technology through East West Information Systems Ltd (EWIS)., Sri Lanka’s first IBM Personal Computer dealership, and media through ETV, later evolving into Swarnawahini.

By starting from the bottom of the stack, Wijesuriya learned to manage complexity, deliver consistently, and build credibility — lessons that underpinned his subsequent ventures in offshore bunkering, ship salvage, and high-profile hospitality projects.

Scaling Without Shortcuts

As East–West expanded, Wijesuriya’s trajectory reflected a preference for measured scaling rather than speculative leaps. His ventures extended into offshore bunkering, ship salvage, and towage, yielding significant commercial success. Businesses were professionalized, governance structures put in place, and operations expanded in line with capacity. This approach later culminated in his association with East–West Properties PLC, bringing parts of the group into the listed-company environment. For Sri Lankan entrepreneurs, this transition is not trivial. Public markets impose disclosure, scrutiny, and a level of discipline many privately held businesses never experience. That step — from founder-led operations to formal corporate structure — is often where local enterprises falter. Surviving it is an achievement in itself.

A Defining Public Chapter: Hospitality

Wijesuriya entered wider public consciousness through his role in the acquisition and stewardship of the Ceylon Continental Hotel, later rebranded by Dhammika Perera via Hayleys plc, as The Kingsbury, Colombo. He also contributed to landmark hospitality projects such as the Marriott Hotel, Weligama, showcasing the same disciplined approach he applied to logistics. Hotels are unforgiving businesses, sitting at the intersection of tourism cycles, security risk, labourmanagement, and international perception. Operating one successfully in Colombo — particularly through years of national turbulence — required more than capital; it required resilience.

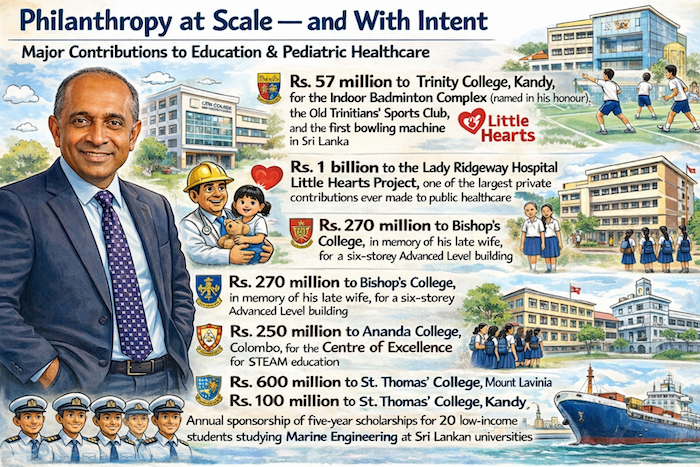

Philanthropy at Scale — and With Intent

Coming from a distinguished family of medical professionals, with six doctors in his immediate family, Wijesuriya combines the precision of an engineer with a deep-rooted sense of compassion and service. In recent years, he has become prominent for large-scale philanthropy, particularly in education and pediatric healthcare.

His contributions — including substantial funding for school infrastructure and a landmark donation to the Lady Ridgeway Hospital “Little Hearts” project — stand out not merely for their size, but for their focus. These are investments in systems, not symbols: hospital wards, medical capacity, educational facilities. They mirror the same pattern evident in his business life — an emphasis on foundations rather than gestures.

Some of his major philanthropic contributions include:

• Rs. 57 million to Trinity College, Kandy, for the Indoor Badminton Complex (named in his honour), alongside initiatives like the Old Trinitians’ Sports Club, the College Computer Centre, and the first bowling machine in Sri Lanka

• Rs. 1 billion to the Lady Ridgeway Hospital Little Hearts Project, one of the largest private contributions ever made to public healthcare in Sri Lanka

• Rs. 270 million to Bishop’s College, in memory of his late wife, for a six-storey Advanced Level building • Rs. 250 million to Ananda College, Colombo, for the Centre of Excellence for STEAM education

• Rs. 600 million to St. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia

• Rs. 100 million to Girls’ High School, Kandy, for a swimming pool complex

• Annual sponsorship of five-year scholarships for 20 low- income students studying Marine Engineering at Sri Lankan universities

The Broader Lesson: Why This Story Belongs in “Made in Sri Lanka”

Wijesuriya’s relevance to this series is not that he represents an idealised model of entrepreneurship. It is that his path is replicable in principle, even if demanding in practice. His career illustrates several uncomfortable truths:

• Sustainable businesses are built slower than slogans.

• Operational competence matters more than access.

• Governance is not an afterthought; it is a growth constraint.

A Quiet Counter-Narrative

Sri Lanka’s economic conversation often swings between despair and exaggeration. In that noise, stories like Wijesuriya’s are easily overlooked because they lack drama. Yet it is precisely these quiet counter-narratives — of engineers turned entrepreneurs, of logistics turned property, of private success paired with public contribution — that show what is still possible within Sri Lanka’s constraints.

MADE IN SRI LANKA is not about celebrating success for its own sake. It is about examining how success is built, sustained, and — occasionally — given back.

In that sense, Nahil Wijesuriya’s story is not exceptional because it is unique.

It is exceptional because it is disciplined. And discipline, in today’s Sri Lanka, may be the rarest asset of all. (www.shauketaly.com)