On a gray Thursday in mid-February, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka issued a short, uncompromising press release: residents must transact with one currency inside the country the Sri Lankan rupee. The statement, which threatened fines of up to LKR 25 million and up to three years’ imprisonment for violations, was written as a simple legal clarification. In practice it is a signpost of a larger campaign: to roll back an informal, post-crisis drift toward domestic dollarisation that has quietly reshaped how money changes hands in parts of Sri Lanka’s economy.

That directive blunt, enforceable and public is meant to do more than enforce a rule. It is an instrument in a broader strategy to restore monetary control, rebuild confidence in the rupee, and protect the fragile scaffolding of Sri Lanka’s external finances. The immediate debate is technical: when is it lawful for a domestic merchant to accept a foreign currency and when should the rupee be used? But the deeper debate is political and social: who gains when local transactions migrate into dollars, and what does it mean for ordinary households when pricing, wages and savings shift into a foreign unit?

From crisis-era coping to a parallel currency market

Sri Lanka’s flirtation with domestic dollar use did not appear overnight. During the country’s economic crisis of 2022–2023, spikes in inflation, chronic shortages of foreign exchange and wild swings in the rupee’s exchange rate nudged some businesses and consumers toward pricing in dollars as a hedge against unpredictability. In sectors such as high-end rentals, private education, and services geared to wealthier customers, USD pricing and payments made in dollars became a way to preserve value and avoid daily conversion losses. Local reporting shows the practice had become prominent enough that the Central Bank felt compelled to respond publicly.

Economists who study “dollarisation” warn that when a foreign currency becomes a parallel medium of exchange, the potency of domestic monetary policy is weakened: the central bank’s interest-rate signals and liquidity operations influence only the rupee side of the market, while dollar-priced contracts create their own dynamics. On the global stage, researchers have documented how and why economies tilt toward more stable foreign units in times of stress — a phenomenon the Central Bank appears determined to reverse.

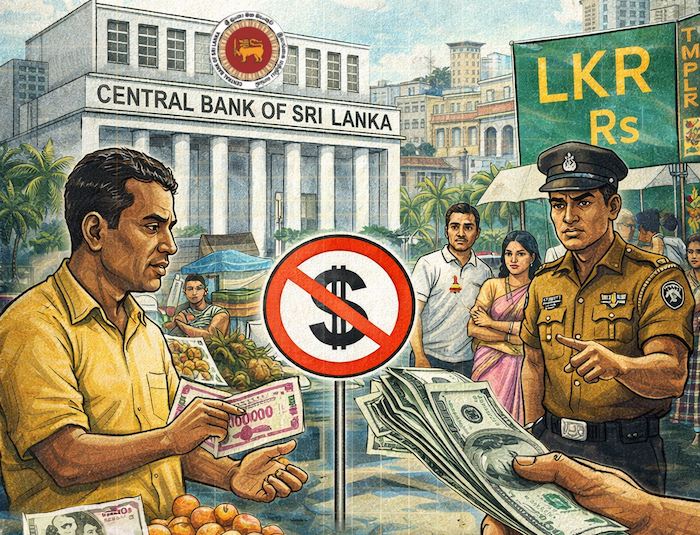

What ordinary Sri Lankans are likely to feel

For most consumers, the order should reduce a subtle, costly form of financial inequality. When some shops quietly insist on dollars, those without access to foreign currency typically lower-income households relying only on rupees face implicit price discrimination and a lower real purchasing power. By insisting on rupee settlement, regulators aim to keep everyday pricing transparent and to ensure that inflation measures reflect the currency that most people use. That, in turn, helps protect social cohesion and makes monetary policy more effective.

But the change will not be frictionless. Businesses that had begun quoting USD prices, or hotels and service providers that accepted direct dollar payments from locals, will face compliance costs: changing point-of-sale systems, retraining staff, renegotiating contracts, and possibly absorbing conversion losses. Tourists and expatriates largely paying in dollars will be unaffected when the counterparty is a nonresident, but the new rule is explicitly aimed at transactions between residents, meaning domestic clients who had turned to foreign-currency deals to avoid rupee volatility will need to adapt. Local reporting suggests some merchants had been quietly converting rupee payments into foreign currency accounts a practice the Central Bank says is unauthorized.

A move to protect reserves and the banking system

The Central Bank’s public notice reflects macro-prudential concerns. Higher implicit local demand for foreign currency whether for safekeeping, to settle contracts, or simply for shopkeepers’ balance sheets — can accelerate pressure on the nation’s foreign-exchange reserves. For a country that has undergone debt restructuring and fragile external finances in recent years, shielding reserves and ensuring orderly foreign-exchange markets is a priority. The bank’s broader policy agenda for 2026 emphasizes creating a more resilient foreign-exchange market and reducing distortions that complicate exchange-rate management.

Banks and payments firms will be watching enforcement closely. The Central Bank explicitly says it has not authorised merchants to receive payments from local customers to the credit of any foreign currency account. That line targets not just street-level dollar transactions but also the plumbing that allowed rupee payments to be converted into foreign-currency deposits often via card processors or informal arrangements. If regulators move to enforce the ban aggressively, it could curb a set of workarounds that blurred the line between legal foreign-currency inflows (tourism, remittances, export proceeds) and domestic substitution.

Here are the types of merchants and service providers most likely to be affected:

1. Hospitality & Tourism-Adjacent Services

- Boutique hotels, guesthouses, villas and homestays that had been quoting prices in dollars for domestic customers (not tourists).

- Event venues (wedding halls, banquet spaces) that previously set “USD packages” for local clients.

2. Property and Real Estate

- Landlords and property managers renting apartments, holiday homes or commercial spaces in dollars – a common practice during periods of rupee instability to protect against currency risk.

3. Education and Training Providers

- Private schools, coaching institutes, and international schools that accepted dollar payments from Sri Lankan parents for school fees or tuition.

4. Health & Wellness Services

- Private clinics, dental offices, cosmetic service providers and specialized therapists that accepted or billed clients in dollars, especially for high-value treatments.

5. Freelancers & Professional Services

- Consultants, lawyers, accountants, designers who may have kept dollar-denominated pricing for local clients to avoid currency fluctuations.

6. Retail and Online Merchants

- E-commerce sellers or boutique retailers that preferred to display prices in dollars or accept foreign currency payments via payment gateways.

7. Event Organizers & Caterers

- Wedding planners, entertainers, DJs, photographers/videographers who had set dollar-denominated packages for local customers.

8. Businesses Using Workarounds

These include merchants that may have:

- Accepted rupee payment but routed funds into a foreign-currency bank account

- Used payment gateways that automatically converted rupee card payments into dollars for credit

The Central Bank’s statement makes clear that unless explicitly authorized, these practices are now considered unlawful between resident Sri Lankans

Enforcement risks and the political economy

A challenge for authorities will be consistent, proportionate enforcement. Heavy-handed fines and criminal penalties risk stoking backlash among affected businesses from hotels and property managers to private clinics and tutoring centres and could push some activity deeper underground. Uneven enforcement also risks creating an appearance of selective application, which would undermine the Central Bank’s goals. Local reportage suggests authorities are still framing the issue as both a legal clarification and a deterrent; much will depend on how quickly they publish operational guidance for merchants and processors and whether they coordinate with tax and law-enforcement agencies.

The larger gamble: restoring trust in the rupee

At base, the policy is an attempt to reverse a social and economic habit born of fear: when a currency repeatedly loses its purchasing power, people adopt alternatives. Rebuilding trust in the rupee requires both credible monetary policy and visible, predictable outcomes stable inflation, steady access to goods and services, and transparent exchange-rate signals. The Central Bank’s statement is a legal lever toward those ends; success will depend on whether it is accompanied by policies that tangibly reduce the incentives for residents to hold or use foreign currency domestically.

For now, the message from Colombo is clear and uncompromising: the rupee must be the currency of the realm. How quickly that message reshapes everyday practice from landlords’ contracts to how a family pays for a wedding hall will be one of the key tests of Sri Lanka’s economic recovery in the months ahead.