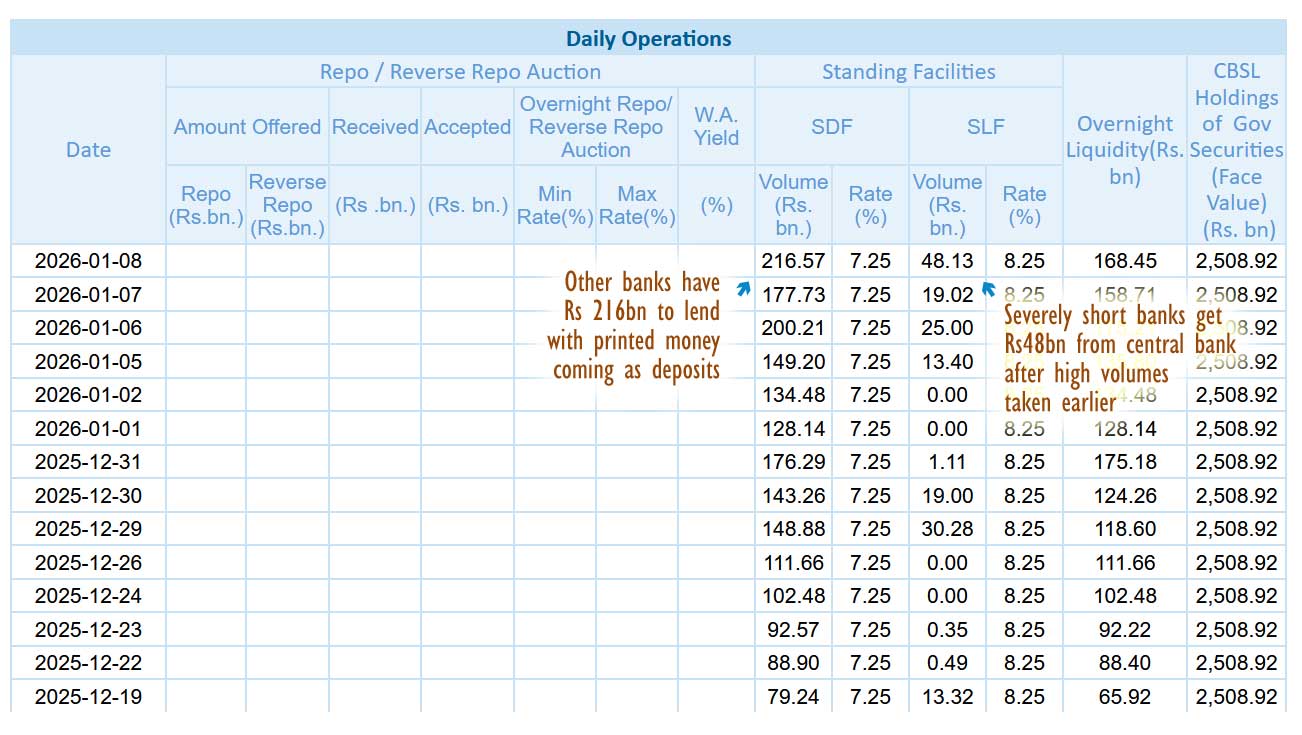

Central bank lending to banks in Sri Lanka surged to 48 billion rupees on January 8, up from 19 billion rupees the previous day, according to official data. Market participants indicated that state banks are experiencing a severe cash shortage.

Sri Lanka’s government had created a “domestic buffer” by overborrowing through bonds and depositing the funds in banks when the central bank controlled public debt. This strategy aimed to manage market interest rates. However, analysts have cautioned that building domestic buffers to maintain low rates is unsustainable. Large withdrawals of deposits could strain interbank markets, while inflationary accommodations by the central bank could negatively impact the exchange rate.

Experts who closely monitor the inflationary policies of Sri Lanka’s central bank since 2015 noted that this “buffer strategy” led to central bank accommodations, currency depreciation, and discredited the country’s economic program.

The domestic buffer was initiated by excessive borrowing even as taxpayer contributions reduced the deficit, during a period when the central bank managed public debt. Typically, a commercial bank receiving a deposit from overborrowed government funds would lend it to other banks, customers, or invest in Treasury bills.

Foreign reserves could increase if the funds are deposited with the central bank, thereby reducing liquidity in the banking system and curtailing credit and imports. However, when liquidity is released and imports are generated through credit, foreign reserves must be returned to prevent currency depreciation.

If the government withdraws deposits from state banks for expenses such as cyclone relief, banks would need to reduce interbank lending first, and then seek loans from other banks. While other banks may eventually receive the cash payments made by the government, they might lend the money to customers for imports or invest in Treasury bills.

Excess liquidity deposited in the central bank reached 216 billion rupees on January 8, a level observed during economic crises and late 2024 when the central bank struggled to accumulate reserves. State banks, which had invested in bills using the “buffer,” had to cease reinvestment in bills, potentially increasing interest rates unless other banks step in to purchase them.

When private credit growth is robust, other banks may not be inclined to buy bills, and the printed money could fuel private credit and imports, exerting pressure on the exchange rate. Classical economists typically advise against borrowing from the banking system, as commercial banks have access to liquidity facilities or can operate with reserve shortages. Central banks might print money to maintain their policy rate, thereby destabilizing the external sector.

In Sri Lanka, natural disasters have often led to reduced private credit and strengthened the currency before the emergence of the “domestic buffer” issue. Following the tsunami, private credit came to a halt, and the central bank allowed the rupee to appreciate in 2005.

(Colombo/Jan09/2026)