Sri Lanka’s central bank had the option to intervene to lower rising short-term interest rates, but these rates decreased on their own before any intervention was necessary, according to Central Bank Governor Nandalal Weerasinghe.

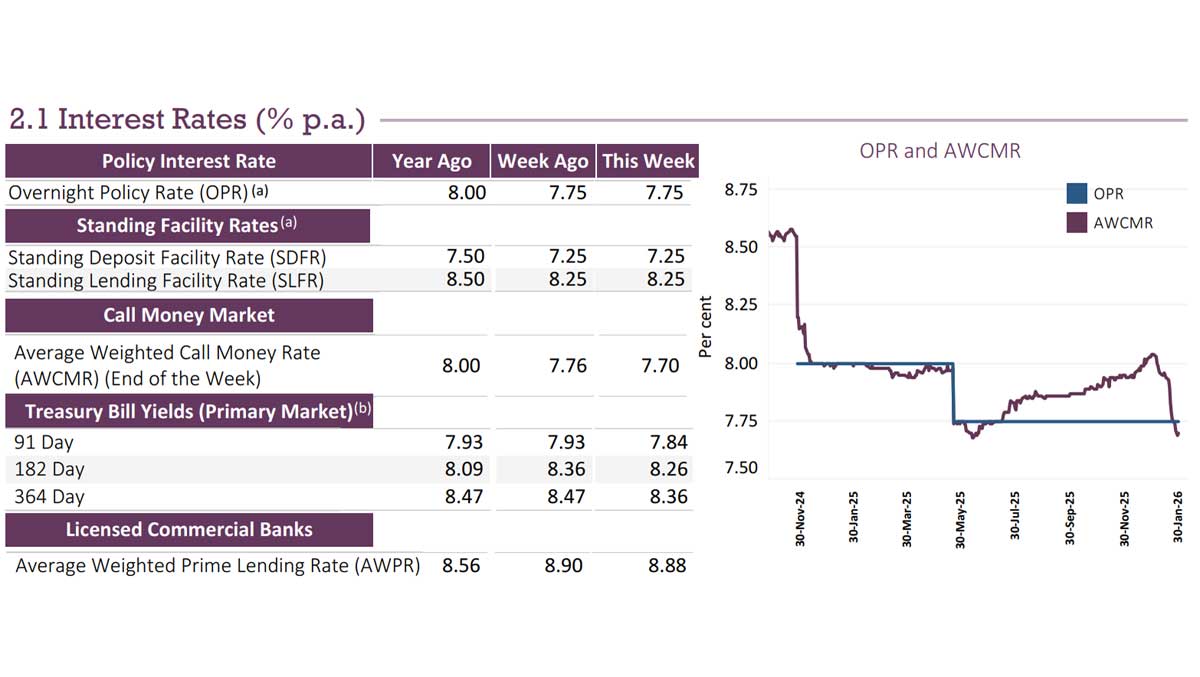

Last year, Sri Lanka’s interbank rates rose above the 7.75 percent overnight policy rate (OPR) as private credit increased up until cyclone Ditwah, along with government relief payments in December. In January, rates began to decline as the central bank increased its dollar purchases and injected more liquidity into the market.

“Banks that were previously experiencing liquidity shortages now have sufficient liquidity, which has resulted in rates returning to a normal level aligned with the OPR,” Governor Weerasinghe stated to reporters after maintaining the policy rate at 7.75 percent. “I see this as a positive sign. If there had been continuous movement in one direction, we might have considered intervention, but there was no need to intervene in the short-term interest rate market, which has now aligned with normal levels.”

He further explained that these rates are gradually influencing other benchmark rates, such as Treasury bills and prime lending rates. Throughout 2025, the central bank permitted short-term rates to increase by operating under a scarce reserve regime, providing banks with liquidity at 8.25 percent. This approach was intended to allow market signals to function effectively and encourage banks to attract deposits rather than relying on central bank credit.

There exists significant public opposition in Sri Lanka to the monetization of deficits or bank balance sheets, as such practices have historically led to currency crises and social unrest. Analysts have noted that in a reserve-collecting central bank operating under a scarce reserve regime, rates would naturally adjust if there was a credit slowdown due to cyclone Ditwah, eliminating the need for rate cuts.

The Public Debt Management Office also allowed Treasury bill rates to rise, which could crowd out private credit (or curb consumption and encourage savings), a shift from previous practices. A slowdown in credit typically results in a balance of payments surplus, enabling the central bank to purchase more dollars or allow the currency to appreciate, or both. Historically, natural disasters have tended to slow private credit, as seen during the tsunami in 2004. There was also a decrease in private credit observed in January 2025 following a surge in late 2024. (Colombo/Jan03/2026)