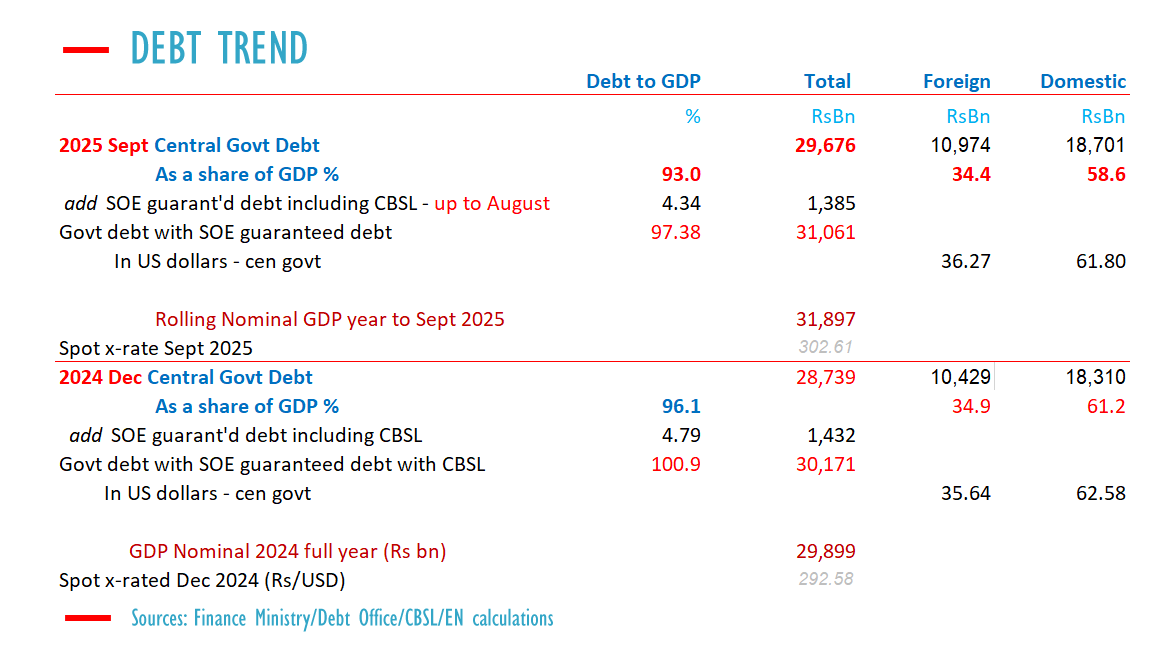

According to official data, Sri Lanka’s central government debt decreased to 93.1% of the gross domestic product (GDP) by September 2025, down from 96.1% at the beginning of the year. However, the issue of currency debasement has intensified during this period.

As of September 2025, Sri Lanka’s domestic debt, calculated in rupees, increased by 391 billion rupees, totaling 18,701 billion rupees. Foreign debt also rose by 545 billion rupees, reaching 10,974 billion rupees, as per central bank debt data.

Treasury-guaranteed debt fell from 1,432 billion rupees (approximately 4.79% of GDP) in December 2024 to 1,385 billion rupees (4.34% of GDP) by August 2025, according to the most recent publicly available data. Consequently, publicly guaranteed debt decreased from 100.9% of GDP in December 2024 to 97.38% by August, based on the rolling nominal GDP for the four quarters ending in September 2024.

The Sri Lankan rupee depreciated from 292.58 to the US dollar to 302.61 by September, attributed to flawed exchange rate policies and excessive dollar purchases that created excess liquidity. This occurred even as citizens paid taxes to improve budgets and national debt. The rupee has since further depreciated to 310 to the US dollar.

During this period, the budget deficit amounted to only 441 billion rupees, as tax payments by citizens and controlled government spending helped manage the situation. However, the debt expanded by 937 billion rupees.

EN’s economic columnist, Bellwether, warns that if the central bank continues to disregard sound monetary policies, tax hikes alone cannot resolve debt crises. Low inflation expectations, due to a failure to anticipate the effects of central bank monetary debasement, may eventually lead to social unrest.

Fiscal gains achieved by then-Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera in 2019 were undermined by the central bank’s currency depreciation and rate cuts, casting doubts on prudent fiscal policy and exacerbating losses in energy enterprises.

Critics argue that macro-economists evade accountability for currency depreciation by asserting that exchange rates are market-determined, although they are influenced by the operational framework of one central bank against another. This trend began in the 1980s, allowing the perpetuation of unsound monetary practices, which led to inflationary pressures and disrupted budgets and economic reforms initiated after 1978.

In contrast, East Asian countries pursued a different path. Exchange rates are determined solely by monetary policy in clean floats, exchange rate policy in hard pegs with no monetary policy, and a combination of monetary and exchange rate policies in reserve-collecting central banks with so-called flexible exchange rates (soft-pegs).

Analysts recommend that the parliament curtail the central bank’s discretionary powers to ensure sound monetary practices and stability. They also urge the termination of monopolies that restrict the Treasury’s access to foreign exchange, thereby preventing a debt trap and minimizing the risk of a second default.

(Colombo/Jan07/2025)