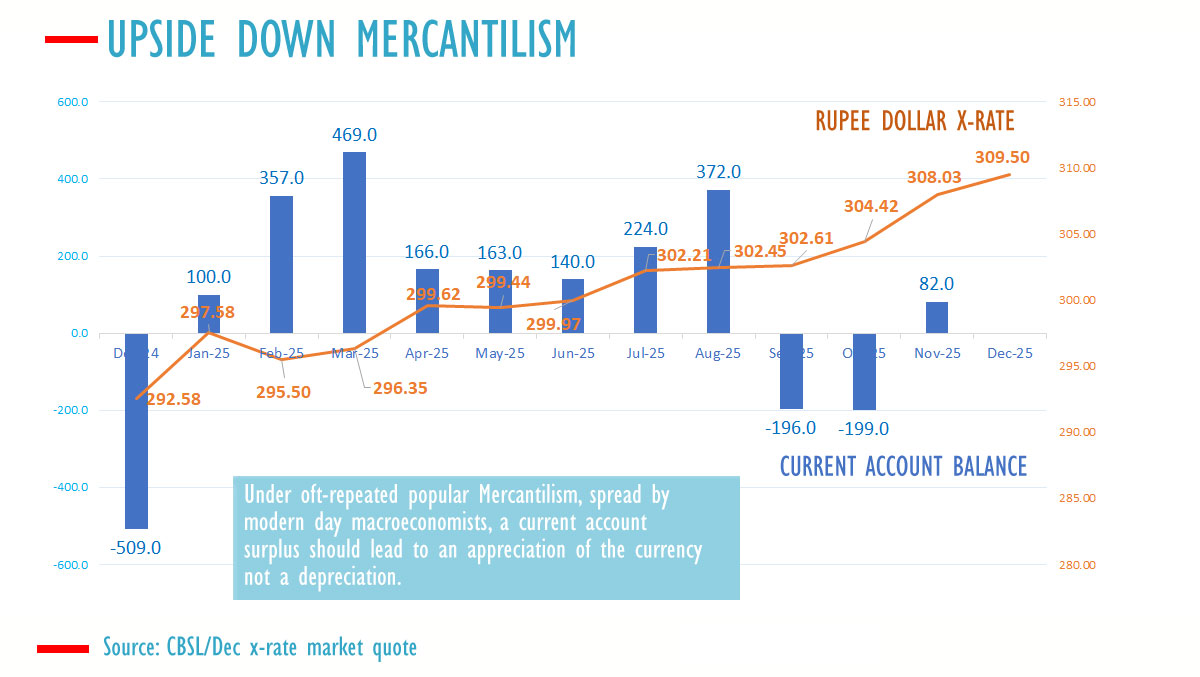

Sri Lanka achieved an external current account surplus of $82 million in November 2025, according to data released by the central bank. This development comes as the Sri Lankan rupee depreciated more significantly compared to October, when a deficit was recorded.

Revised figures indicate that Sri Lanka faced a current account deficit of $199 million in October, following a $196 million deficit in September. During September, the rupee’s value decreased from 302.45 to 302.61 per dollar, coinciding with the $196 million deficit. In October, the currency further weakened by approximately two rupees, reaching 304.61 against the dollar, alongside the $199 million deficit.

A current account deficit typically signals net inflows through the financial account, although this is subject to potential errors and omissions. Conversely, the $82 million surplus in November signifies outflows through the financial account, a situation sometimes described as ‘capital flight’. During this period, the rupee’s value fell by nearly four rupees to 308.03 against the US dollar.

In 2023 and 2024, Sri Lanka recorded current account surpluses, with the central bank maintaining monetary stability to facilitate debt repayments by the central bank, the government, and occasionally the private sector. By 2025, the country had achieved a current account surplus of $1.7 billion, surpassing the $1.2 billion surplus in 2024. Despite this, the rupee depreciated from 292 in December 2024 to 308.03 by November 2025 and further to 309.50 by the end of December 2025.

Historically, macroeconomists and mercantilists have attributed external financial difficulties to current account and budget deficits. However, these explanations are now being questioned. Analysts have cautioned that the flexible exchange rate policy, which diverges from classical economics, is leading to rupee depreciation as the central bank purchases dollars contrary to its deflationary policy.

The central bank’s dollar purchases create new money, a process referred to as the monetization of the balance of payments by the first Governor, John Exter. Unless this liquidity is absorbed through deflationary measures, the central bank must return the dollars at the original purchase rate to prevent further rupee depreciation, which occurs when rupees are converted into imports or used for debt repayments.

While the central bank has returned dollars to the government, it initially withheld returns to private importers, allowing excess liquidity to be converted into imports. Analysts have highlighted that inconsistent currency policies, such as selectively denying convertibility and employing both pegging and floating rate strategies, can lead to confidence shocks, prompting importers to secure currency early and exporters to delay sales.

There have been calls for the Treasury to purchase dollars in the market and impose dollar-denominated taxes on those capable of paying, thus removing a privilege afforded to the central bank to avert a second default from inflationary policies. Analysts warn that if the central bank resumes inflationary measures to maintain overnight or other rates by injecting liquidity through open market operations or buy-sell swaps, forex shortages could arise.

Since its establishment, Sri Lanka’s central bank has seen the rupee depreciate from 4.70 to 310 against the US dollar. In 2004, the rupee appreciated following the tsunami, as private credit sharply declined in January. (Colombo/Jan01/2025)