Sri Lanka, through its Treasury, is currently seeking budget support and dollar-denominated loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Asian Development Bank, and foreign governments to secure the foreign currency needed for debt repayment.

If such external funding is not obtained, the Treasury is advised to rely on foreign exchange reserves held by the central bank, according to prevailing macroeconomic perspectives. However, when these reserves decline, both foreign and local investors become increasingly uneasy.

The Mid-Year Fiscal Review noted, “Additionally, the receipt of approximately USD 350 million from the IMF’s fourth tranche significantly contributed to alleviating USD liquidity pressures, thereby supporting the maintenance of the treasury’s cash flow.” The report highlighted Sri Lanka’s critical dependence on external financial support to meet its external debt obligations and emphasized the importance of strategic liquidity management amid limited foreign exchange reserves.

Yet, the assertion that Sri Lanka must depend solely on external sources for dollars is being questioned. Over the years, the Treasury has been managed by macro-economists, often seconded from the central bank, which may have shaped this prevailing mindset. While not inherently malicious, these professionals tend to prioritize monetary policy tools and political policy rates, having set aside more traditional economic theories.

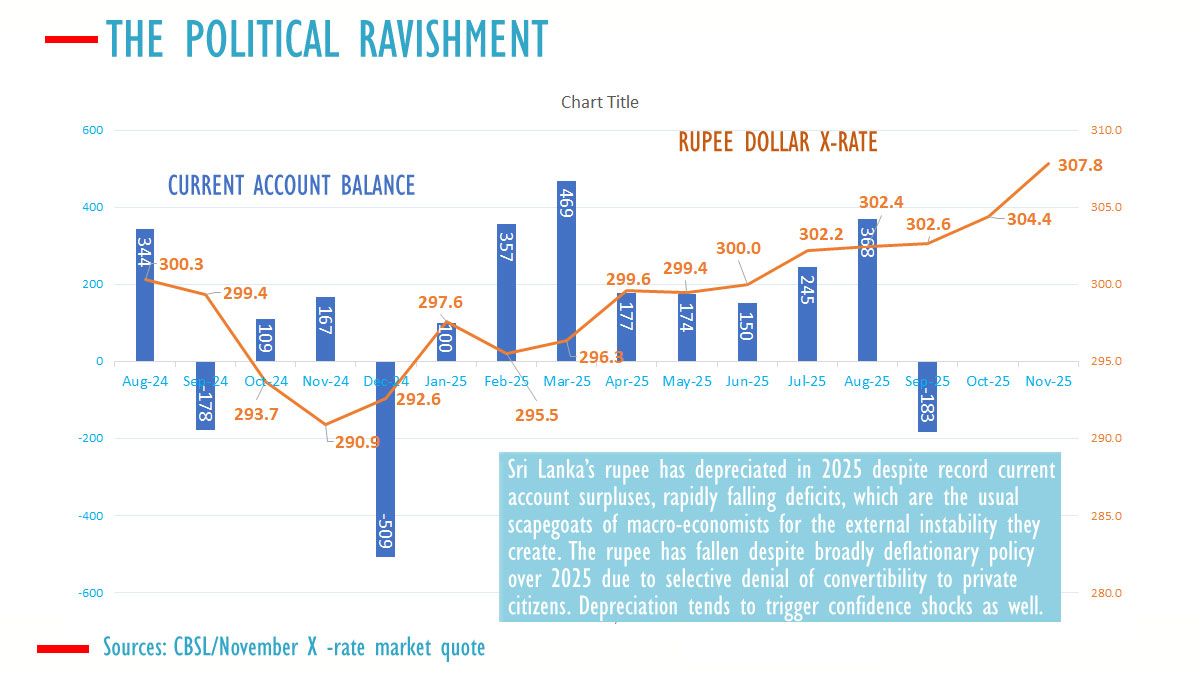

This analysis was originally published in the December 2025 issue of Echelon Magazine, following the Treasury’s expressed concerns about the need for additional foreign loans, as outlined in the Mid-Year Fiscal Review. At the time, Sri Lanka faced challenges such as Cyclone Ditwah, limited reserve accumulation due to the absence of active deflationary policy within the IMF program, the implications of a 5 percent inflation target, and continued currency depreciation. The country has since sought a new IMF program and is requesting further budget support loans. The history of peacetime defaults, which began with currency depreciation in the 1980s, suggests that unless the central bank’s operating framework is reformed and inflationary policies are addressed, the risk of repeated defaults remains.

In reality, the Treasury has access to significant streams of dollar revenue, but these are effectively blocked by the central bank’s monopoly over foreign exchange.

The Foreign Exchange Monopoly

The current structure requires the Treasury—and by extension, the nation—to seek dollars externally or rely on monetary reserves tied to currency issuance because macro-economists have restricted other avenues for acquiring foreign exchange. The central bank holds a monopoly over foreign exchange transactions.

A key reform to prevent another default would be to liberalize this monopoly and enable the Treasury to collect taxes in dollars. Allowing such a system would reduce the country’s vulnerability to future defaults and better protect the public interest.

After years of flexible inflation targeting and open market operations, it is crucial for Sri Lanka to move away from monetary doctrines that have contributed to its economic challenges. Many countries with similar frameworks have experienced repeated defaults following the IMF’s Second Amendment.

Dollars Are Available, But Not for the Treasury

The distinction between rupees and dollars is minimal as long as the central bank avoids inflationary policy. It is unnecessary for the Treasury to borrow dollars from abroad—or even domestically—to service debt. Instead, the Treasury could directly collect tax revenues in dollars from those able to pay, such as exporters, tourist hotels, BPO companies, and freelancers, provided current restrictions are lifted.

Institutions like Airport and Aviation Services and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority could also pay value-added tax and other levies in dollars. Banks, which manage rupee credit, are similarly positioned to pay taxes in foreign currency.

Government Acceptance and the Risk of Default

The Treasury’s inability to access foreign currency is rooted in the central bank’s privileged position. Historically, central banks in the West gained credibility by securing the exclusive right to have taxes paid in their issued notes—a privilege granted by governments. This created demand for their currency but also established a monopoly that now restricts the Treasury’s access to foreign exchange.

Under a fixed exchange rate and without inflationary bias, this arrangement posed little risk. However, today the Treasury is dependent on the reserves of a note-issuing central bank with a political policy rate. Reluctance to pursue deflationary policy and a focus on a 5 percent inflation target have heightened the risk of default.

Previously, when currencies were backed by gold or silver and central banks lacked political policy rates, this privilege did not threaten government solvency as long as convertibility was maintained. In the United States, the government once paid debt interest in gold, a practice discontinued after the Federal Reserve’s creation and the onset of inflationary policies.

Following economic crises, macro-economists have convinced governments that such exclusive privileges are standard practice, when in fact they are not.

The Urgency for Reform

The central bank’s depreciation of the currency in 2025, despite current account surpluses, indicates that fundamental issues in its operating framework remain. As seen in other countries, currency depreciation after IMF programs can lead to social unrest, even without default.

Any return to inflationary policies would make it difficult for the central bank to accumulate reserves. Without sufficient deflationary action—such as selling government bonds to absorb excess liquidity—the situation could deteriorate rapidly.

Historical examples, such as Sri Lanka’s experience in 1952 and the Bank of England’s crisis in 1825, illustrate how quickly conditions can worsen after periods of stability if sound monetary policy is not maintained.

The Central Bank’s Limitations

The central bank is not well-suited to build reserves on behalf of the Treasury, especially when it uses inflationary open market operations. When it buys dollars in exchange for newly printed money, it creates a liability—the previous owner of the dollars now holds rupees, which can be used to demand foreign exchange in the future, putting pressure on the currency.

To retain reserves indefinitely, the central bank must acquire dollars in exchange for non-circulating assets, such as government bonds, rather than newly issued currency. This requires running deflationary policy to neutralize the liquidity created when purchasing foreign exchange.

The Treasury, on the other hand, can accumulate reserves by purchasing dollars with existing funds, without expanding the money supply. Historically, this was achieved through external or sinking funds rather than relying on the central bank.

The IMF’s reserve metrics are based on flawed principles. Building external funds, either for specific loans or as part of a sovereign wealth fund, would be a more effective approach.

There is also an inconsistency: while the central bank advises businesses not to borrow in foreign currency unless they have matching dollar revenues, it prevents the Treasury from collecting taxes in dollars, despite its own heavy foreign currency borrowing. This monopoly places the nation at unnecessary risk, primarily to preserve the central bank’s control.

For 75 years, the central bank’s exclusive privilege has constrained the Treasury’s access to foreign currency, to the detriment of the public. It is now up to Parliament to reconsider and revoke this privilege to protect the country from future defaults linked to the inflation target and single policy rate.

Sri Lankans deserve the opportunity to move away from these restrictive policies—a chance lost since the adoption of inflationary policy in February 1952.