Financial Chronicle – The Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) of Sri Lanka has submitted a proposal to the regulatory authorities, seeking an 11% increase in electricity tariffs. This request is prompted by escalating oil prices and a depreciating rupee, despite the presence of record current account surpluses and a decline in global crude prices. The depreciation of the rupee has also led renewable energy investors to denominate their tariffs in US dollars due to the inadequacy of the so-called flexible exchange rate system, which fails to serve as a reliable unit of account or standard of deferred payment.

The CEB’s proposal for a tariff increase is based on an exchange rate of 308.65 rupees to the US dollar, compared to the 303.33 rupees per dollar rate used in their previous request from May 2025.

Falling Global Energy Prices, Rising Sri Lankan Prices

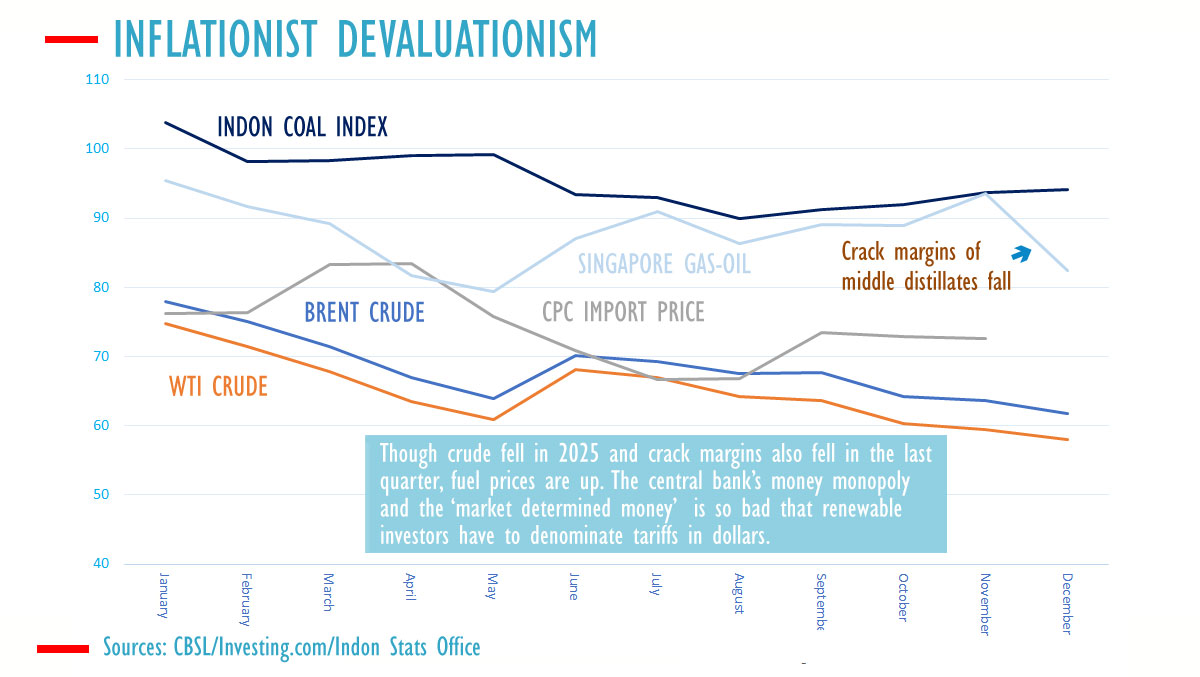

In 2025, global fuel and coal prices declined due to broadly deflationary policies by the Federal Reserve, though future risks to commodity prices remain as quantitative tightening has ended. Despite these global trends, the CEB’s price assumptions reflect higher diesel costs. Singapore gas oil prices, as reported by Platts, decreased from 95.41 to 82.37 dollars in December, although there was a slight increase from mid-year lows of 79 dollars. The easing of refinery capacity shortages has also reduced previously high crack margins.

The CPC’s crude import prices fell from 76 dollars per barrel in January and 75 dollars in May to 72 dollars in December 2025. However, the diesel price used in CEB’s 2026 proposal rose from 274 rupees per liter in May to 277 rupees, and further to 279 rupees in January, despite global crack margins easing.

Coal prices also saw a decline in 2025, with Indonesia’s coal index dropping from 103.74 in January to 94.17 in December. However, projected coal prices for the first quarter of 2026 are lower than those in May 2025 when a price hike request was denied by the regulator. The depreciation of the rupee poses a significant challenge to the government’s plans to reduce electricity production costs to 25 rupees, potentially undermining election promises, analysts warn.

Despite the rising energy prices due to currency depreciation, there is a possibility that this could help meet the central bank’s high inflation target of 5%, as the government’s economic program faces challenges and public dissatisfaction grows.

Escaping Accountability

Sri Lanka’s central bank began to avoid accountability for exchange rate instability around 1980, following the International Monetary Fund’s second amendment to its articles. This led to inflation levels exceeding those of the Great Inflation period, complicating budget management. As Sri Lanka entered repeated IMF programs in 1981 and 1984, labor unrest and social tensions escalated, coinciding with a second civil war. To maintain power amidst currency depreciation, elections were manipulated.

Advice from Singapore’s economic architect, who established the non-inflating Singapore Monetary Authority based on currency board principles, was rejected by Sri Lankan macro-economists. In a 1980 policy paper, Goh Keng Swee warned then-President J R Jayewardene of the rupee’s depreciation from 15.445 to 18.060 per US dollar within 11 months, a fall of 16.9%. He cautioned that unless reversed, the country could face a vicious cycle of increasing domestic money supplies, import demand, depreciating exchange rates, higher import costs, and greater central bank credit creation.

Goh emphasized the political ease of addressing the cycle early, warning of high political costs once entrenched, as illustrated by Poland’s struggles at the time. Poland defaulted in March 1981, becoming one of the first victims of the IMF’s Second Amendment, and declared Martial Law in December to suppress the Solidarity movement as the currency continued to fall. Similar fates befell Latin American countries with aggressive open market operations and commercial borrowings in the 1970s.

When Sri Lanka defaulted in 2022 due to flexible exchange rates and potential output targeting after a decade of foreign borrowing, inflation soared to 70%. Despite historical lessons on stabilization crises from printing money for growth, macro-economists continue to advocate for 5 to 7% inflation annually to spur growth, even after recent growth exceeded the potential output of 3.1% following the elimination of inflation.

Depreciation and Prices

“In Sri Lanka’s case, a rupee depreciation necessitates increases in administered prices, a politically unpopular measure,” Goh informed JR. “Many products with administered prices are either wholly imported or contain a significant import component. All wheat for flour and bread, kerosene, and milk powder are imported. Bus fares are largely influenced by the rupee price of imported oil and spare parts, and fertilizers are mostly imported.”

Exchange rate policies involve complex technical issues that Goh refrained from discussing in detail. The exchange rate is an outcome of the central bank’s operational framework, encompassing both monetary and exchange rate policies. Depreciation occurs when exchange rate policy conflicts with monetary policies, while appreciation happens when they are complementary.

Analysts attribute the rupee’s depreciation in 2025 to the central bank’s exchange rate policy of excessive dollar purchases, despite a deflationary policy enacted after cutting rates in March to boost credit. The central bank’s deflationary policy is now confined to the coupons the Treasury pays on its restructured bond stock, minor amounts of long-term bonds, and any terminated buy-sell swaps. However, the central bank has slightly improved its operating framework by allowing interbank rates to rise and reverting to a scarce reserve regime. (Colombo/Jan08/2026)