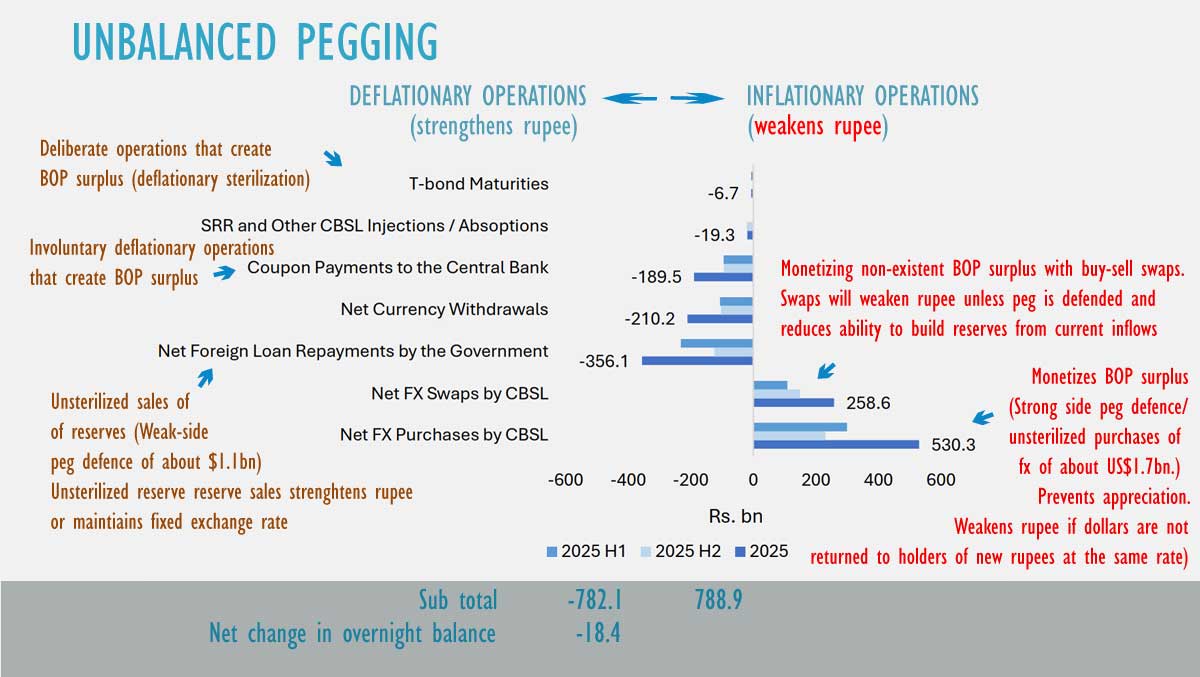

FINANCIAL CHRONICLE – Recent data from Sri Lanka’s central bank reveals that it has sold 356.1 billion rupees (approximately 1.1 billion US dollars) of foreign exchange to the government to facilitate debt repayment, thereby averting further depreciation through unsterilized reserve sales.

The central bank has also generated 530.3 billion rupees of new money by purchasing dollars on a net basis, equating to about 1.7 billion US dollars at an average exchange rate of 301 rupees. This effectively monetizes a balance of payments surplus.

Unsterilized dollar purchases inject liquidity into the market, causing overnight rates to decrease and potentially triggering increased imports through consumption and investment credit. Given Sri Lanka’s high private saving rate, credit is necessary to convert all dollar receipts into imports, as consumption alone is insufficient.

In contrast, an unsterilized dollar sale for debt repayment reduces liquidity and elevates overnight rates, counteracting the impact of dollar purchases and strengthening the currency.

However, if inflationary open market operations are used to narrowly target overnight rates—often referred to as soft-pegging or a flexible exchange rate—additional credit is financed with non-existent deposits, leading to excess demand for dollars. This can result in currency depreciation in countries where the central bank narrowly targets short-term rates after defending a peg, eventually leading to a loss of confidence and potential sovereign default.

Beyond dollar sales for debt repayment, cash from dollar purchases was also diminished by 189.5 billion rupees through coupon payments made by the Treasury to the central bank’s rupee bond portfolio. Net currency withdrawals, which can arise from a demand for money in the economy and expand notes in circulation, amounted to 210.2 billion rupees.

The central bank also allowed the deflation of approximately 6.7 billion rupees by permitting the redemption of Treasury bonds purchased during previous crises, which violated a long-held bills-only policy meant to target long-term rates.

Any money mopped up in this manner reduces domestic investment credit and imports, triggering a balance of payments surplus that can be monetized by purchasing dollars. In 2025, the central bank further increased buy-sell swaps, effectively monetizing bank offshore balance sheets rather than current inflows or a balance of payments surplus, creating 258.6 billion rupees in new money.

When banks distribute rupees to customers through loans or to the government as taxes, and the central bank does not return dollars to importers at the same rate, monetary depreciation occurs.

Sri Lanka’s rupee experienced rapid depreciation in 2025, which analysts described as a result of political mismanagement due to flaws in the central bank’s operating framework, despite broadly deflationary policies. This depreciation was exacerbated by reserve sales not being executed at the same exchange rate as purchases, as noted by analysts.

Globally, currency depreciation was prevalent between World War I and World War II due to monetary instability without war, as indiscriminate open market operations and the policy rate originated by the Federal Reserve spread to other Western nations and Latin America.

(Colombo/Jan06/2026)