Sri Lanka’s Treasury is able to manage its debt repayments up to the first two months of 2026 with support from Asian Development Bank (ADB) loans and a Rapid Finance Instrument, according to Damitha Rathnayake, Additional Director General of Treasury Operations.

During a hearing of the Committee on Public Finance, Rathnayake explained that the government had initially planned to use the anticipated US$350 million International Monetary Fund (IMF) tranche for debt servicing. She was responding to questions raised by opposition member Ravi Karunanayake.

The fifth review of Sri Lanka’s IMF program was originally scheduled for completion in December. Rathnayake stated, “From the side of the government, we were planning to use the cash inflow from the IMF loan for debt service. However, we have received US$270 million from the ADB, and another US$100 million is expected before December 31. With these funds, we can manage the remaining debt service obligations in December and for the first two or three months of the next year.”

Rathnayake added that if there is a delay in receiving the next IMF tranche, the Treasury will purchase dollars from the central bank. Such purchases reduce the government’s net foreign loans.

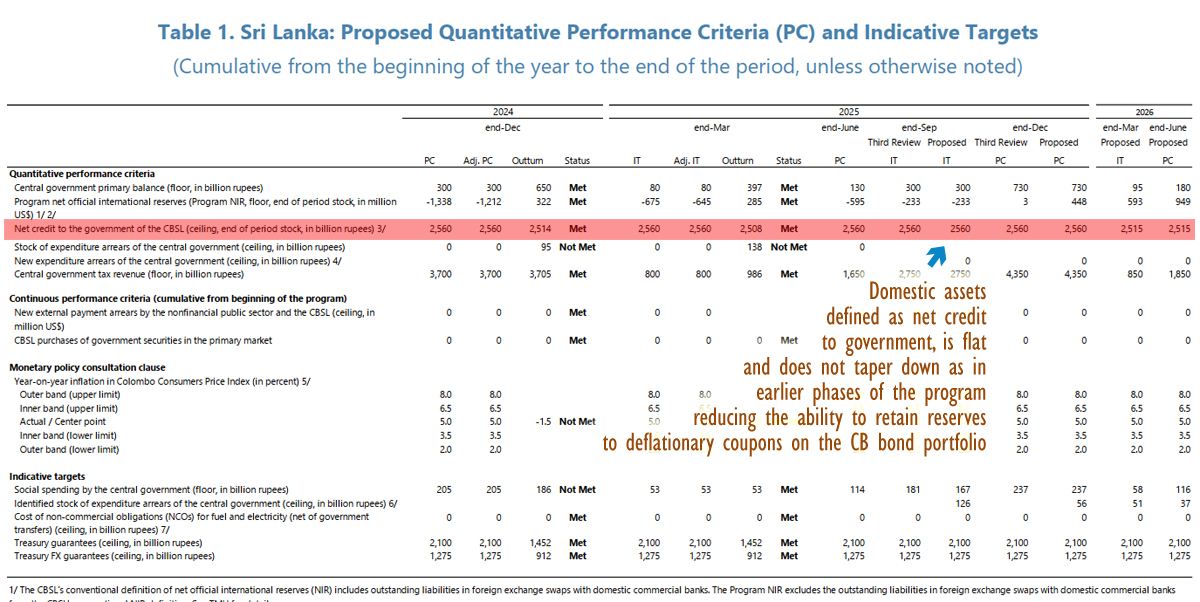

However, Sri Lanka’s central bank has not been able to accumulate as many dollars in 2025 as it did in 2023 and 2024. This is partly due to a lack of adequate deflationary policy within the current IMF framework, which does not require the central bank to reduce its bond holdings. Additionally, the controversial interest rate cut in May 2025 has affected this process.

Analysts have suggested that the central bank should convert its bonds into marketable instruments, or at least strip some coupons and sell the separated instruments as deep discount bonds, which are easier for buyers to price.

Under the new central bank legislation, a provision allowing the appropriation of foreign reserves without impacting the monetary base has been removed. Critics argue that this change undermines classical economic principles. As a result, any dollar sales by the central bank to the Treasury now reduce liquidity in the banking system.

If liquidity is already low due to reduced central bank purchases of dollars, maintaining a single policy rate could lead to money being printed as bank balance sheets are monetized through open market operations. This situation could create actual foreign exchange shortages.

In 2025, deflationary policy has been limited to the coupons of the central bank’s step-down securities and residual marketable bonds acquired during previous currency crises. Throughout the year, the central bank has selectively limited convertibility for private citizens while over-purchasing dollars in relation to its deflationary policy. This has contributed to a depreciation of the rupee and a reduction in dollar purchases compared to periods of more active deflationary measures.

In October and November, the central bank’s dollar purchases dropped to levels barely sufficient to cover its own reserve-related liabilities.

Analysts have recommended that the Treasury build its own reserves—such as external sinking funds or sovereign wealth funds—which would be neutral in terms of reserve money. They also warn that the IMF’s Assessing Reserve Adequacy (ARA) metric is based on flawed assumptions, as monetary reserves are inherently linked to reserve money.

Any dollars the Treasury acquires for rupees, as well as those bought from the central bank (except via buy-sell swaps), come from current account flows and serve to reduce the country’s foreign debt stock. Analysts note that reliance on loan funds for debt repayment resembles previous practices of “borrowing its way out of rate cuts” observed after the end of the civil war.

The Treasury currently faces restrictions, as it is not permitted to buy dollars in the market like other importers, and its natural dollar revenue streams are also blocked due to a “Government Acceptance” privilege granted to the central bank, analysts say.

(Colombo/Dec 21, 2025)