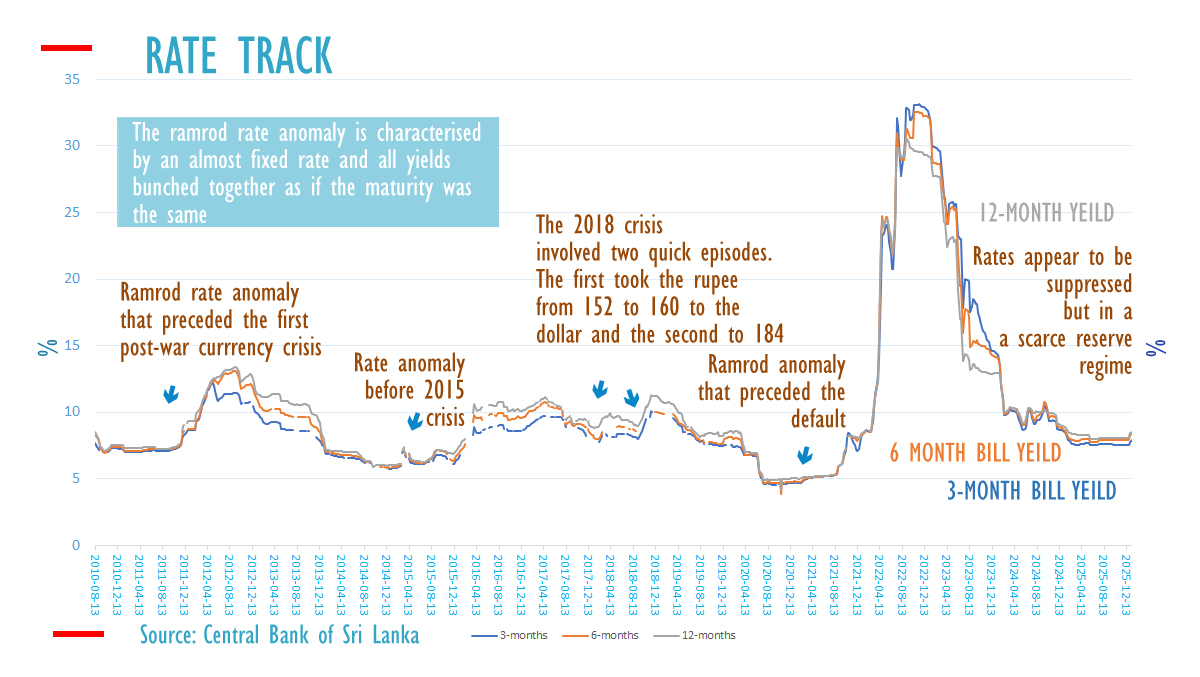

Sri Lanka’s Treasury bill yields have experienced a slight increase, disrupting the unusually flat and compressed rates observed across various tenures over recent months. This pattern has often preceded currency crises. Historically, when public debt was managed by the Central Bank, Treasury bill rates were artificially suppressed following rate cuts. These measures were enforced through inflationary open market operations, which swiftly led to foreign exchange shortages and currency depreciation.

In 2025, a regime of scarce reserves was implemented, reducing money printing through domestic operations, and non-market interest rates were imposed via ‘signalling.’ Despite this, the rupee depreciated as excess liquidity accumulated from over-purchases of dollars, surpassing the Central Bank’s deflationary policy. Analysts refer to this situation as a ‘monetization’ of a balance of payments surplus, a concept introduced by the founding Governor of the Central Bank, John Exter.

The Ceylon Electricity Board in Sri Lanka has requested an increase in tariffs as the rupee depreciated, even though global fuel prices have decreased. Fuel prices were raised in January. Following the end of the civil conflict, Treasury yields were reduced to levels where they became ineffective as a benchmark for pricing corporate debt, shifting reliance to average weighted deposit rates instead.

A rapid increase in Treasury bill yields signals the market about the government’s fiscal needs, which may be temporary or seasonal, potentially crowding out private credit. It is not necessary for long-term yields to rise if the long-term fiscal outlook is favorable and the currency remains stable, preventing capital destruction.

Sri Lanka’s rate cuts occurred amid robust private credit growth, under so-called flexible inflation targeting and data-driven monetary policy. Analysts caution that statistical models disregarding economic theories, primarily Hume’s price-specie flow mechanism and Ricardo’s principles, might lead to external challenges for a reserve-collecting central bank.

A swift pass-through of fiscal pressures or private credit could also elevate deposit rates, increasing savings and reducing consumption. Since the controversial rate cut in May, Sri Lanka’s deposit rates have also climbed. Banks embarked on a deposit-raising campaign towards the end of the year.

“Banks were heavily competing for deposits, constrained by interest rate controls,” stated a senior finance company official. “However, the ‘noise’ about deposits has diminished based on advertising and social media activity.”

In 2025, finance companies were borrowing from banks through credit lines as they struggled to attract deposits, according to another official. However, credit line restrictions have since eased. Some lenders reported a decline in demand for vehicle loans after the Central Bank increased the loan-to-value ratio, even before cyclone Ditwah hit. Meanwhile, vehicle importers noted a drop in sales in December.

Amid strong private credit concerns, questions arose whether Sri Lanka’s reserve collections would fall short, as had occurred after rate cuts in the post-war period, resulting in substantial foreign borrowings and eventual sovereign default. Analysts emphasized that the ‘buffer’ is not historical reserve collections, but rather ongoing interest rates that curb private credit and imports, facilitating easier debt servicing.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised its reserve projection, identifying a $700 million external financing gap in 2026. Unlike other importers or government departments, Sri Lanka’s Treasury does not purchase dollars and relies on central bank dollars or dollar debt. Analysts have highlighted a debt trap stemming from an ancient privilege granted to historical central banks, known as ‘Government Acceptance,’ which constrains the Treasury’s dollar revenue streams and increases dollar debt, irrespective of tax hikes on individuals and businesses.

(Colombo/Jan19/2026)