Colombo, Sri Lanka – Nearly four years after Sri Lanka entered into its much-publicised International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme, fresh data on public debt and foreign exchange reserves point to an increasingly precarious economic position, raising serious questions about the effectiveness and outcomes of the reform agenda.

According to an analysis of official figures, by November 2025 around 44 months had elapsed since the government embarked on the IMF-supported programme, accompanied by sharp tax increases and the introduction of so-called “cost-reflective” pricing for utilities. Despite these measures, government indebtedness has continued to rise rapidly, while foreign reserve buffers remain alarmingly weak

Exploding Public Debt

At the end of December 2021, before IMF engagement, Sri Lanka’s total public debt stood at Rs. 17.6 trillion, comprising Rs. 11.1 trillion in domestic debt and Rs. 6.5 trillion in foreign currency debt (about USD 32.5 billion). At that time, with GDP estimated at USD 88.6 billion, the IMF and several local experts declared the debt “unsustainable”

However, by March 2022—coinciding with the IMF’s entry—public debt had surged to Rs. 21.7 trillion. A significant portion of this increase was driven by the sharp depreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee, a policy adjustment long advocated by IMF-aligned economists. Foreign currency debt alone rose to Rs. 9.6 trillion, even though the dollar value of debt remained broadly unchanged.

The upward trajectory continued. By April 2023, roughly one year into the IMF programme, total public debt had climbed to Rs. 26.8 trillion, while GDP had contracted to USD 76.8 billion. Notably, the earlier warnings about “debt unsustainability” grew quieter, despite a 52% increase in debt compared to end-2021 levels.

By end-December 2024, the debt stock reached Rs. 28.7 trillion, and by June 2025 it had risen further to Rs. 29.6 trillion—representing a staggering increase of Rs. 12 trillion over less than four years, with no commensurate growth in economic output.

Reserves: A Fragile Illusion

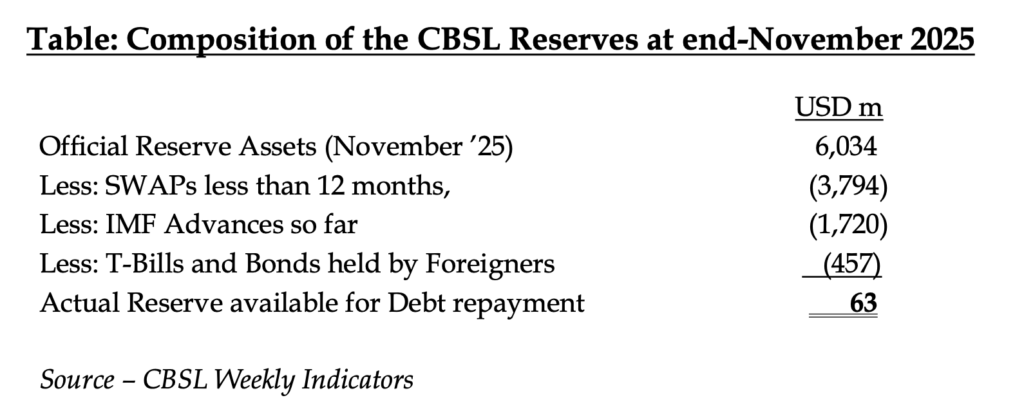

The foreign exchange reserve position is equally troubling. After Sri Lanka declared a default and suspended external debt repayments in April 2022, authorities projected that savings from non-repayment would allow the Central Bank to accumulate around USD 3 billion annually, potentially building a USD 10 billion buffer by the time repayments resumed.

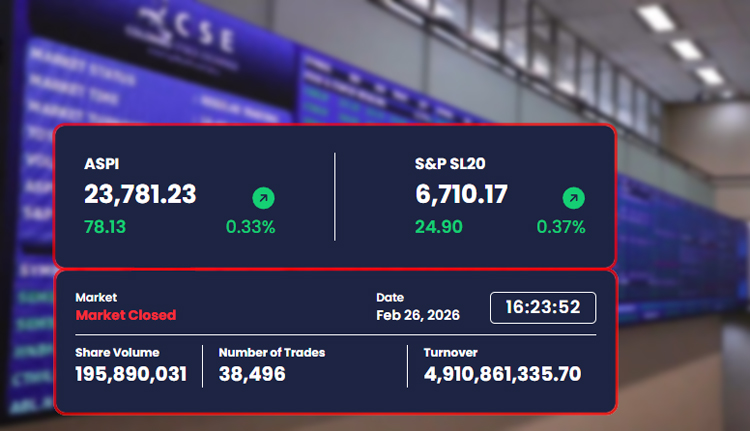

That expectation has not materialised. As of end-November 2025, official reserves stood at USD 6.03 billion. Critically, the bulk of this figure is tied up in short-term swaps (USD 3.79 billion), IMF disbursements (USD 1.72 billion), and foreign investments in Treasury bills and bonds (USD 457 million) that could be withdrawn at short notice. Once these components are excluded, only about USD 63 million remains as reserves genuinely available for future debt repayment

A Bleak Outlook

Economists warning of long-term risks argue that the most alarming aspect of the situation is not merely the low level of usable reserves, but the absence of any meaningful reserve build-up despite nearly four years of a “debt holiday.” Compounding this concern is the lack of clear policy initiatives capable of delivering strong economic growth, export expansion, or sustained foreign exchange inflows in the coming years.

As Sri Lanka prepares for the eventual resumption of external debt repayments, these figures suggest that the IMF programme—while stabilising certain short-term indicators—has yet to place the economy on a durable or self-sustaining path. With debt higher than ever and reserve buffers wafer-thin, the country may be facing an even more challenging adjustment phase than the one that triggered the crisis in the first place.