- Modest growth of around three percent

- Inflation stabilising near five

- Describe an economy that is standing upright, not one that can sprint.

Growth at this level restores lost ground; it does not build shock absorbers. It does not generate enough fiscal space to respond generously to disasters, invest aggressively in climate adaptation, and protect living standards simultaneously.

This is where the conversation becomes politically inconvenient.

Sri Lanka’s economy today can likely withstand one moderate shock without spiralling into crisis. It cannot withstand two overlapping ones — a climate event coinciding with an external financial tightening, or a geopolitical disruption layered onto domestic stress. In that scenario, familiar trade-offs return quickly: austerity versus relief, reform versus revolt, credibility versus compassion.

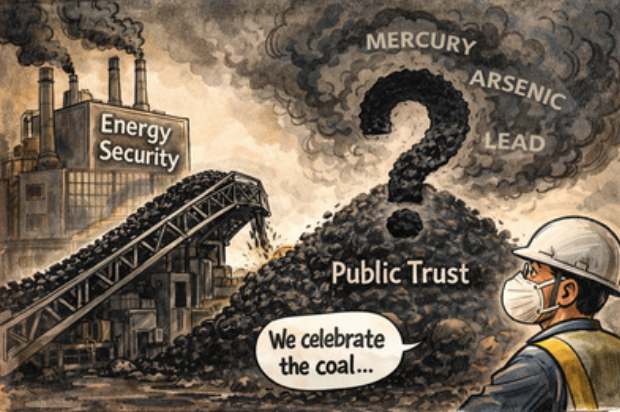

The risk is not immediate collapse. The risk is slow erosion — of reform discipline, of public trust, of political patience. Each shock chips away at the social contract, asking citizens to endure again, tighten again, wait again. Eventually, even the most resilient population asks a fair question: to what end?

Supporters of the current path argue, not incorrectly, that there is no alternative. That loosening fiscal controls would invite another crisis. That discipline must precede development. All true. But discipline alone is not a development strategy. It is a holding pattern.

What is missing is a credible national conversation about shock management — not as an emergency response, but as economic architecture. Climate adaptation funding, insurance mechanisms for agriculture, decentralised energy resilience, and disaster- ready infrastructure are not environmental luxuries. They are macro-economic stabilisers. Treating them as secondary will simply ensure that the next cyclone, drought, or flood shows up as a fiscal crisis rather than a weather event.

There is also a political dimension the spreadsheets don’t capture. Reforms survive not because they are technically sound, but because they remain socially tolerable. Each shock narrows that tolerance. Each appeal to patience has a diminishing return. Governments do not fall when indicators worsen; they fall when people conclude that endurance has become a permanent policy.

So where does this leave Sri Lanka as 2026 unfolds?

Stable, but exposed. Recovering, but not resilient. Better governed than in 2022, yet still operating close to its margin of error. The economy has not run out of shocks; it has run out of room for complacency.

The real test for this government will not be whether it can maintain IMF targets in calm conditions. It will be whether it can hold the reform line when the next shock arrives — without asking the public to carry the full weight yet again.

Because the question Sri Lanka is now asking itself is not rhetorical.

It is arithmetic.

How many shocks can this economy take — before stability stops being a plan and becomes a prayer? (www.shauketaly.com)