In the 2024 presidential and parliamentary campaigns, the combined NPP/JVP made one pledge unusually clear and unusually loud: those responsible for the alleged Central Bank bond scam of February 2015 would be held accountable. It was not an abstract promise about “system change” or “future reform”. It was specific. Named. Time-bound. Moral.

It resonated because the bond issue was not merely a financial controversy. It had become a symbol — of elite impunity, of blurred boundaries between politics and institutions, and of a state that repeatedly failed to discipline itself.

Two years into governance, with an NPP/JVP Executive President and 150 Members of Parliament in a 225- seat legislature, that promise remains conspicuously unfulfilled.

No prosecutions concluded.

No new forensic investigations announced. No accountability publicly established.

The opposition, electorally decimated, cannot credibly be blamed for obstruction. Institutional power is not fragmented. It is consolidated.

Which raises an uncomfortable question: what happened to the promise once it encountered the machinery of the state?

A Scandal Defined by Conflict, Not Just Loss

Even at its most conservative framing, the February 2015 bond controversy raised issues that went far beyond yield curves and auction mechanics. The core concern was conflict of interest — perceived, structural, and unresolved.

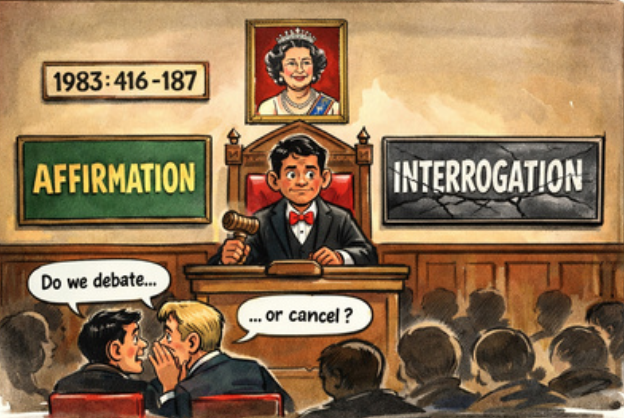

That framing was repeatedly articulated on Newsline (TV1), where several current NPP/JVP leaders — including Sunil Handunnetti, Vijitha Herath, Nalinda Jayatissa, — appeared over the years to criticise the events surrounding the bond issuance.

Their argument was consistent: even if criminal liability were contested, governance failure and conflict of interest were undeniable. That position helped anchor public outrage and legitimise demands for accountability.

Yet today, the very leaders who advanced that critique now preside over a state that has not reopened — or meaningfully advanced — a forensic reckoning.

We labour the point that it is a forensic analysis that will uncover the real events – devoid of politics. The previous forensic analysis included Central Bank paper that was issued in previous terms – mainly possibly for political expediency.

Decision makers have been so quick off the mark to attempt a prosecution of wasted public finances, visiting locations far away – more to the point thousands of dollars expended – only to obtain statements from those who may well have been able to do so using modern tech – like on Zoom for instance, although it wont quite generate the same optics of a physical team being sent ‘sent out’ there. The amount in question pales into total insignificance when compared to the aggregated total of the alleged ‘Bond scam’.

The Question of Institutional Boundaries

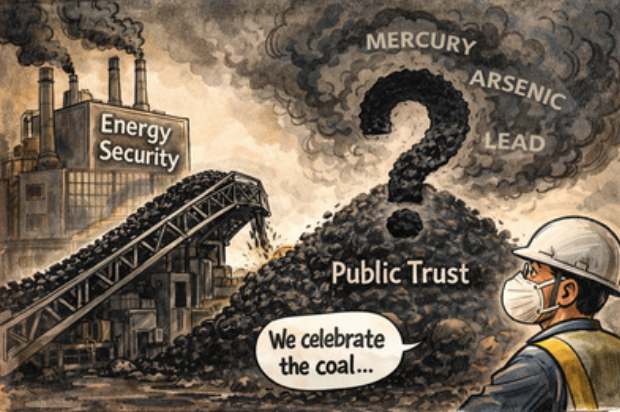

One aspect of the 2015 period continues to sit uneasily within the public record yet has not been subjected to transparent forensic scrutiny.

Malik Samarawickrama was, at the time, Chairman of the United National Party (UNP) — a principal partner in the ruling coalition. In that capacity, he held no statutory role within the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, nor any formal institutional mandate that would ordinarily require his presence there.

It is therefore notable — and remains insufficiently explained — that he reportedly attended a breakfast meeting at the Central Bank, alongside ministers and senior officials, to meet the then Governor, Arjuna Mahendran. The issue of Samarawickrama’s presence at this meeting must be forensically investigated. Appearances will suggest that Samarawickrama is being protected – in the event that his role, his presence at the ‘Breakfast’ meeting is not subject to forensic audit and investigation. Mahendran, a Singaporean citizen, was widely regarded as politically close to the UNP. Prior to his appointment as Governor, he had served as Chairman of the Board of Investment, during a previous UNP administration, under a premiership of the party, at a time when Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga was President.

The issue here is not an assertion of wrongdoing. It is a matter of governance propriety.

What institutional purpose did a political party chairman serve in discussions at the Central Bank? What topics were discussed? What access was afforded — formally or informally — and to whom?

In jurisdictions serious about institutional independence, such questions are examined precisely because they precede allegations of loss. Sri Lanka has not conducted such an examination.

Power Without Excuses

The NPP/JVP cannot plausibly argue incapacity:

They control the Executive.

They dominate Parliament.

They command investigative agencies through constitutional authority.

If anything, they possess more latitude than any government in recent memory to initiate independent, well-scoped, and transparent investigations — insulated from political vendetta and judicial overreach.

Yet the record shows hesitation.

Is it caution?

Is it fear of precedent?

Or is it the realisation that forensic scrutiny, once unleashed, is rarely selective?

Accountability Deferred Is Accountability Denied What distinguishes reformist governments from rhetorical ones is not denunciation in opposition, but discipline in power.

Investigations need not presume guilt.

They need not pre-judge outcomes.

They need only establish facts — access, influence, process, and compliance with institutional norms.

To date, that has not occurred.

The silence is not neutral. It actively erodes the moral authority with which the NPP/JVP once spoke on corruption, governance, and elite privilege.

The Risk of Becoming What You Replaced

Sri Lanka has seen this pattern before. Governments elected on moral clarity gradually substitute reform with stability, and accountability with quiet.

The bond issue was never just about 2015. It was about whether Sri Lanka could finally draw a line — not between parties, but between politics and institutions.

Two years on, that line remains undrawn.

And every month of inaction turns a promise of accountability into something far more damaging:

Precedent.

Bottom line

No court has yet established final culpability in the public imagination.

No investigator has been publicly tasked with revisiting unresolved governance questions.

No explanation has been offered for why those who once demanded answers now avoid asking them.

For a government elected on the promise of systemic change, this silence is not incidental.

It is The Story.