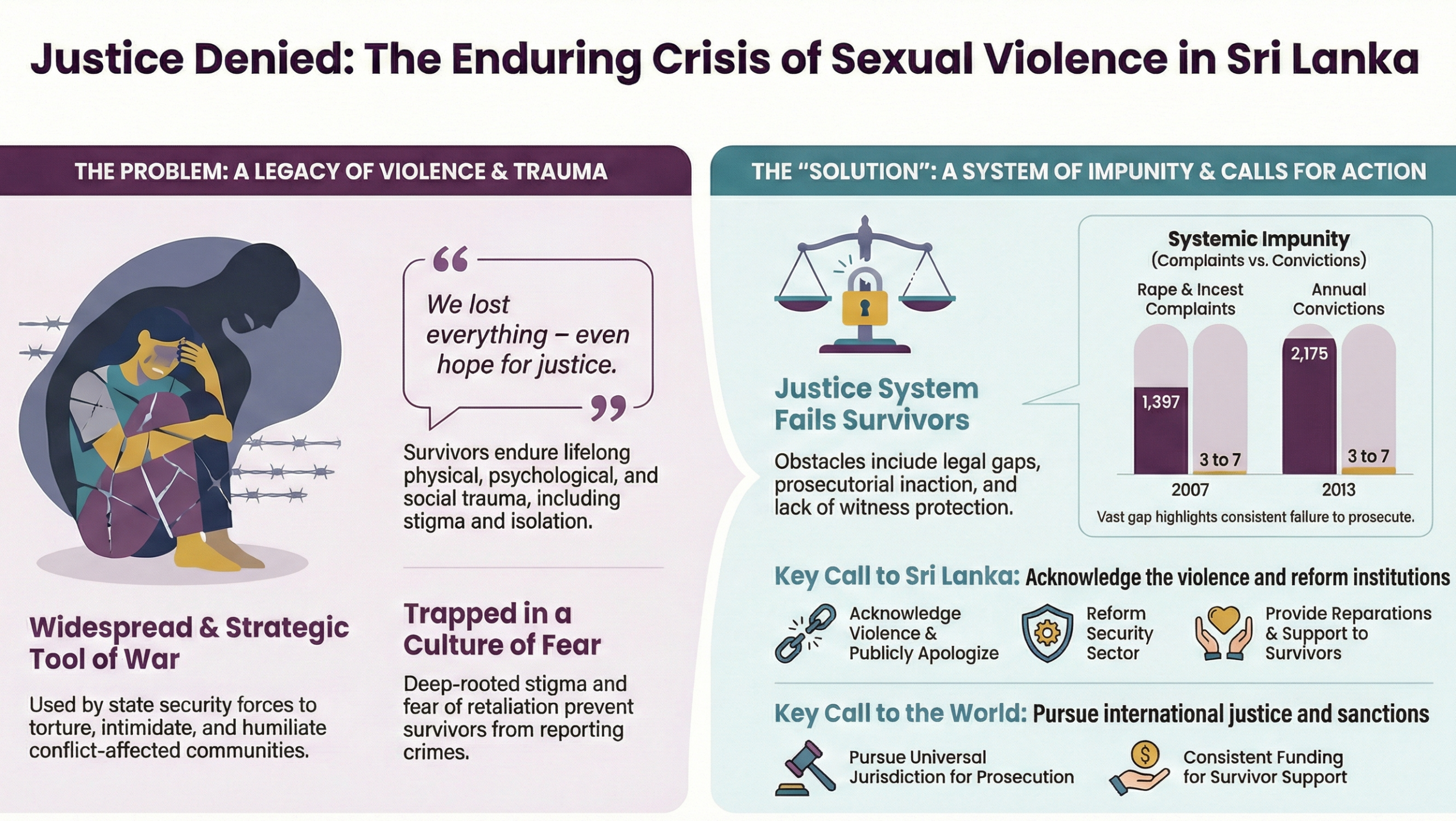

The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has released a report highlighting the ongoing challenges faced by survivors of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) in Sri Lanka, more than 16 years after the end of the country’s civil war. Titled “We Lost Everything – Even Hope for Justice,” the report was published on January 13 and is based on over a decade of UN monitoring, previous investigations, and direct consultations with survivors.

The report documents the use of sexual violence as a deliberate and widespread tool during and after the 26-year conflict between Sri Lanka’s state armed forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). These acts, which disproportionately targeted Tamil communities, included rape, gang rape, sexual torture, forced nudity, genital mutilation, and sexual humiliation.

According to the report, perpetrators were primarily state security forces, including the army, navy, air force, Criminal Investigation Department (CID), Terrorism Investigation Division (TID), and affiliated paramilitary groups. These entities used violence to extract information, assert dominance, intimidate populations, and instill pervasive fear.

“Despite it being a longstanding matter of record, successive Sri Lankan governments have failed to adequately investigate or prosecute cases of conflict-related sexual violence, often minimizing or denying the extent of the violations,” the report states. “While international actors have expressed concern, meaningful steps toward facilitating credible accountability and access to justice for survivors have remained limited.”

The report notes that the current government has pledged a renewed focus on domestic accountability and justice reform, including commitments to address some emblematic cases and restore the rule of law. However, entrenched impunity for serious violations, including CRSV, persists, and tangible progress remains to be seen.

The report adopts a survivor-centered methodology, adhering to “do no harm” principles with confidentiality and informed consent. Due to restricted access to Sri Lanka, OHCHR conducted remote semi-structured interviews and focus groups with 27 survivors (23 women and 4 men, aged 26–86), covering incidents from 1985 to as recently as 2024. Consultations also included civil society experts, legal professionals, and academics.

Survivors’ testimonies paint a harrowing picture of enduring trauma. One woman described the acts as “a torture that never stops,” while another lamented: “We lost everything, our husbands, kids, and dignity. No one can give that back. All we have is this suffering.” A male survivor reflected on survival amid brutality: “I was happy to be alive and that was enough.”

Many victims emphasized community-wide harm, with one stating: “Such violent acts were carried out to take out the dignity of the Tamil community. These are crimes against the community.”

The report highlights how impunity has perpetuated a continuum of gender-based violence, with post-conflict militarization in the North and East, emergency laws like the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), and weakened rule of law enabling ongoing violations. Stigma silences survivors; women face ostracism, marital rejection, and economic hardship, while men endure emasculation and untreated injuries. Children of survivors, including those born of rape, suffer discrimination.

Domestic legal gaps exacerbate the crisis, and prosecutions remain rare even in emblematic incidents like the 2011 Vishvamadu gang rape case, which saw initial convictions overturned on appeal. Reparations are virtually nonexistent, with no comprehensive programs or official acknowledgment.

The report references President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s November 21, 2024, inaugural address, where he pledged to investigate “controversial crimes,” deliver justice to victims, and restore trust in the rule of law. Yet, nearly 15 months later, “tangible progress remains to be seen,” with structural conditions enabling impunity unchanged.

The report lists recommendations and urges the Sri Lankan government to publicly acknowledge past CRSV by state forces and issue a formal apology, as well as conduct independent, survivor-centered investigations, including command responsibility. It also suggests reforming laws, including adopting consent-based rape definitions and repealing PTA provisions enabling arbitrary detention, while providing holistic reparations, psychosocial support, and targeted schemes for male survivors and affected families.

Additionally, the report calls for enhanced security sector vetting, oversight, and human rights training, as well as the removal of war monuments from civilian areas as a symbol of acknowledgment. Internationally, it advocates for universal jurisdiction prosecutions, targeted sanctions on perpetrators, screening of Sri Lankan personnel in UN peacekeeping, and sustained support for OHCHR evidence preservation under Human Rights Council resolutions.

Human rights groups have echoed the urgency. Amnesty International’s South Asia Director, Smriti Singh, described the report as “a clarion call” for accountability, noting it reaffirms that sexual violence against Tamils was “deliberate, widespread, and systemic.”

As Sri Lanka navigates economic recovery and political transitions, the OHCHR report warns that without genuine political will to confront this legacy, cycles of trauma, marginalization, and violence will persist, eroding prospects for lasting reconciliation and healing.

(Colombo/January 14/2026)