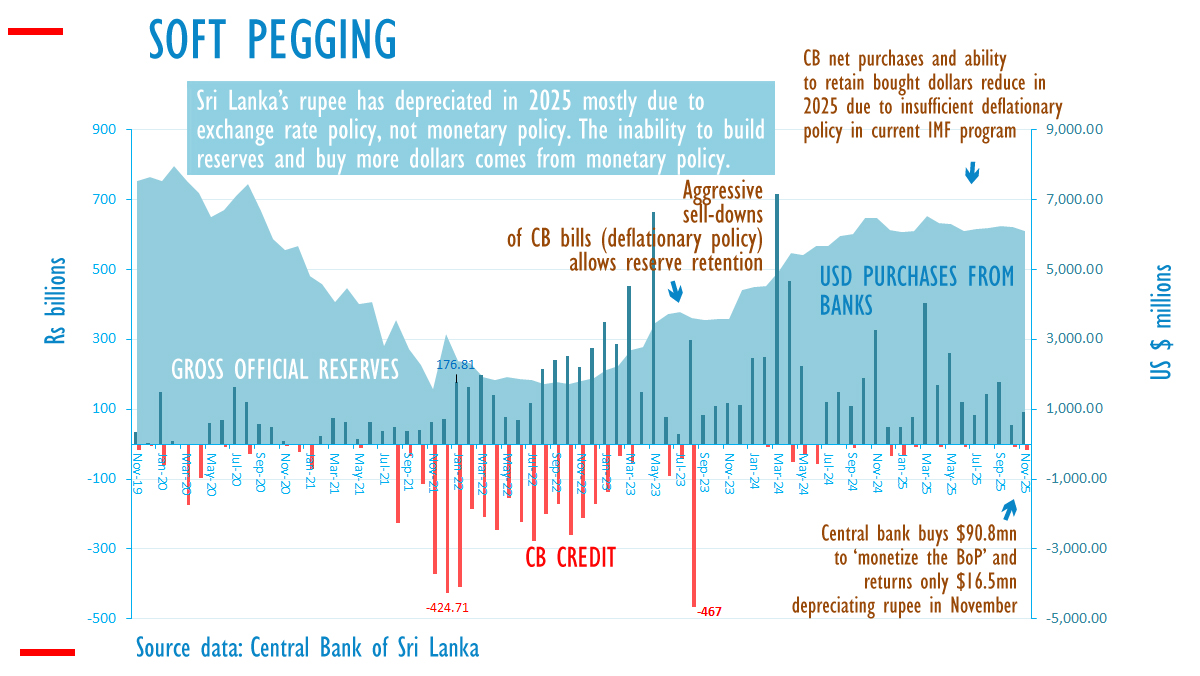

Sri Lanka’s central bank purchased 90 million US dollars in November 2025, creating new money, while returning only 16.5 million dollars to importers who utilized these funds, according to official data.

On a net basis, the central bank bought 74.3 million US dollars in November, following the collection of 45.5 million dollars in October. This activity was accompanied by a depreciation of the rupee. In October, the rupee fell from 302 to 304 against the US dollar, and in November, it declined further from 304.40 to nearly 307.80 in the spot market as the central bank continued its dollar purchases.

Unlike other market participants, when the central bank purchases dollars, it creates new money—an action described by the bank’s first Governor, John Exter, as the monetization of the balance of payments.

“A central bank is supremely unqualified to build reserves,” says EN’s economic columnist, Bellwether. “An ordinary man on the street can hide 100 dollars under his mattress, forgo spending, and build reserves. The Treasury can also do that. But a central bank cannot, because it creates new money whenever it buys dollars.”

Unless this new money is withdrawn from circulation, the recipients—such as export sector workers, remittance holders, and bank customers borrowing these funds—will eventually use them for imports. If the central bank does not return the corresponding dollars, the excess rupees will ultimately lead to a depreciation of the currency.

To prevent the new money from returning to the foreign exchange market, the central bank would need to withdraw it by selling its own securities. In 2025, the central bank purchased a total of 1,625 million dollars but returned only 89.3 million dollars to the public. Some of the dollars were returned to the government, which also helped reduce excess liquidity.

During 2023 and 2024, the central bank acquired substantial volumes of dollars and retained them by reducing its Treasury bill holdings. However, in 2025, under the revised International Monetary Fund (IMF) program, the central bank was no longer required to sell down its bond holdings. As a result, deflationary policy—necessary for creating a balance of payments surplus—was limited to the coupons paid by the Treasury on its bonds.

Claims by macro-economists that the rupee is “market determined” have been challenged, as the exchange rate is actively managed when the central bank purchases dollars to build reserves or to supply the government. In a clean float, exchange rates are determined solely by monetary policy, such as an inflation target. In a hard peg, they are determined by exchange rate policy. Flexible or discretionary regimes, by contrast, combine unpredictable monetary and exchange rate policies.

Analysts have warned that the central bank would be unable to accumulate more reserves unless it further reduced its bond holdings. Additionally, the central bank’s decision to cut rates in May, despite warnings that it was inconsistent with domestic credit conditions, contributed to increased credit and higher imports of investment goods.

In December, Sri Lanka requested another loan from the International Monetary Fund, diminishing hopes that the current IMF program would be the country’s last.

(Colombo/Dec19/2025)