When the NHS UK Lost the Plot — and What Sri Lanka Gets Right (and Wrong)

There was a time when invoking the National Health Service ended arguments.

Universal. Free. Civilised.

A moral achievement wrapped in policy.

Today, that invocation draws a weary shrug.

Britain’s NHS — after fourteen years of Conservative stewardship — is not merely strained. It is structurally exhausted. Patients now routinely walk into A&E only to be told, without irony, that the wait to see a doctor is eight to nine hours. Ambulances queue outside hospitals like delivery trucks waiting for dock space. “Emergency” has become a semantic courtesy, not a clinical guarantee.

This is not a staffing glitch. It is a systems failure.

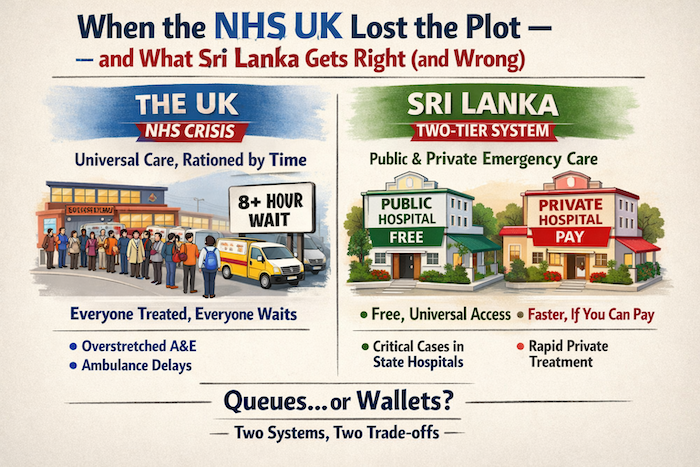

The UK: Universal Care, Rationed by Time

In the UK, A&E is almost exclusively NHS-run. There is no meaningful private emergency alternative. This is deliberate policy. Emergency medicine is unpredictable, expensive, and loss-making. The private sector stays out; the State absorbs everything.

The result is moral clarity — and operational overload.

Everyone is treated. Everyone waits.

Triage is clinically strict, not consumer-friendly. A broken arm may wait behind a silent stroke. That is medically sound — but politically combustible. And when exit block prevents patients from moving into wards, the entire system clogs. Ambulances cannot offload. Corridors become holding bays. Time, not money, becomes the rationing mechanism.

The NHS still delivers excellent outcomes in major trauma and critical care. Survival rates remain among the world’s best. But access has degraded so severely that the public now experiences the system as indifferent — even when it is clinically competent.

That erosion of trust is fatal to public health.

Sri Lanka: Two Systems, One Emergency Reality

Sri Lanka’s emergency care model is messier — but in some respects more pragmatic.

Here, emergency care is split between public hospitals and private providers, under the oversight of the Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. The public system remains universal and free. The private system exists — not as ideology — but as pressure relief.

So what happens if you’re in a car crash?

The answer is simple and often misunderstood: You are taken to the nearest public hospital A&E.

Severe trauma, mass casualties, unconscious patients — these go straight to state hospitals. Not because private hospitals are incapable, but because public hospitals are structured to absorb unpredictability at scale. Teaching hospitals handle neurosurgery, polytrauma, and overflow that no private balance sheet can tolerate.

Private hospitals in Sri Lanka do operate 24/7 emergency units, particularly in urban centres. For cardiac events, strokes caught early, or stabilised emergencies, private care can be dramatically faster — minutes rather than hours. But access is conditional. Payment, insurance, and capacity matter.

In Sri Lanka, money buys speed.

In the UK, no amount of money buys time.

Outcomes, Not Anecdotes

Here is the uncomfortable truth both sides avoid.

The UK delivers slower emergency access, but more equal survival. No one is turned away. No deposit is demanded. No family negotiates at a cashier while a patient bleeds.

Sri Lanka delivers faster emergency access for those who can pay, while the public system quietly absorbs the heaviest, ugliest cases — often under-resourced, often overcrowded, but remarkably resilient and very much

The dual system masks stress. Britain has nowhere to hide it.

How the UK Lost the Plot

Fourteen years of ideological neglect hollowed out the NHS’s elasticity. Bed capacity was cut. Social care was underfunded, blocking hospital flow. Staff morale collapsed under political gaslighting. What was sold as “efficiency” turned out to be fragility.

The NHS was never designed to be lean.

It was designed to be redundant — and redundancy costs money.

Sri Lanka, paradoxically, preserved redundancy through informality: family caregiving, private spillover, and clinician improvisation. None of it is pretty. Much of it is unjust. But it prevents total gridlock.

The Real Comparison

So when someone says, “The UK NHS is failing — Sri Lanka is better,”

they are usually comparing one system carrying everyone with two systems sharing the load.

That is not an honest comparison.

The real question is this:

Do we want emergency care rationed by queues — or by wallets?

The UK chose time.

Sri Lanka chose money.

Both choices have costs.

But only one pretends it doesn’t.