Sri Lanka is gradually emerging from an external sovereign default, often compared to similar situations in Latin America. This default was triggered by macroeconomic policies aimed at targeting potential output through high inflation, supported by unsound monetary practices. Over the past two years, Sri Lanka has experienced a rare period of stability as the central bank missed its inflation target, with economic growth rebounding to about 4 to 5 percent.

Despite this recovery, Sri Lanka faces renewed threats of currency depreciation and external economic challenges. The money supply is being inflated through ad hoc changes in issuing rules, including inflationary open market operations, buy-sell swaps, foreign exchange surrenders, and selective denial of convertibility. These measures are used to manipulate rates or devalue the currency, leading to rising prices that benefit some economic players at the expense of others, a phenomenon known as the Cantillon effect, particularly when inflation expectations are low.

This instability in monetary systems is not unique to Sri Lanka; it is also prevalent in advanced nations that have engaged in stimulus measures and rely on single policy rates, such as floor systems. Consequently, people in these countries are experiencing economic hardships, and government finances are struggling due to stimulus efforts.

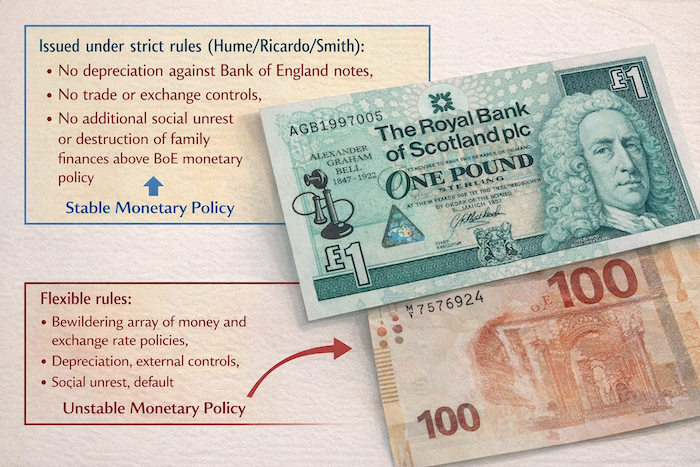

In a recent interview, Lawrence H. White, Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, sheds light on the history of money and the current state of instability. The discussion explores why soft-pegs or flexible exchange rates are popular in unstable countries, why the IMF promotes regimes with inconsistent rules where crises are almost inevitable, why inflation targets have failed to control central banks, and why central banks pursue growth or employment with high inflation targets, despite historical lessons.

Professor White, an expert in the theory and history of banking and money, is the author of several notable works, including “The Clash of Economic Ideas” (2012) and “The Theory of Monetary Institutions” (1999). His extensive background includes roles as a visiting research fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research, a visiting lecturer at the Swiss National Bank, and a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. He is also a co-editor of Econ Journal Watch and serves on the board of associate editors for the Review of Austrian Economics.

Q: Can you provide a brief overview of past monetary institutions?

A: Historically, a diverse range of commodity standards existed, with people using shells, silver, and barley in different regions. As agriculture and trade expanded, there was a convergence on gold and silver, especially after coinage was developed, making it easier to assess the quantity and quality of received metals. In ancient societies, such as Rome, Greece, and India, silver standards and coins were common, sometimes produced by governments and sometimes by private moneyers.

Governments Take Over Mints

Governments began taking over mints for revenue purposes, often debasing the coins. As European coins were debased, banking systems emerged, providing claims to silver that were more reliable than the physical coins produced by governments. This led to the issuance of paper notes by banks, initially as deposits, and later as notes, in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Most countries adopted a silver standard, while the UK and the US transitioned to a gold standard, with other countries eventually following. Banks issued most of the common currency, with banknotes serving as paper claims payable in gold or silver on demand.

Emergence of Central Banks

Central banks began to develop, with the Bank of England becoming the premier central bank. Although initially unintended, it grew into the role of controlling the national money supply due to its monopoly on banknote issuance. The concentration of gold at the Bank of England enabled it to lend to the government and exert significant influence in financial markets, causing boom and bust cycles.

During the First World War, major combatant countries abandoned the gold standard, and it was not fully restored post-war. The Bretton Woods system, established after the Second World War, pegged the US dollar to gold, with other major currencies pegged to the US dollar.

Unredeemable Fiat Money

In 1971, the US ceased redeeming dollars for gold at $35 an ounce, resulting in major world currencies becoming unredeemable for gold or silver. Exchange rates began to fluctuate, with some countries adopting dollar or euro standards. While central banks in these countries lack control over the money supply, others have full authority over money creation and purchasing power, leading to varying inflation rates. Sri Lanka has experienced significant inflation over the past decade.

Inflation Targeting and Central Banks

Today, political systems aim to constrain central banks through inflation targets rather than fixed exchange rates. However, this approach has had mixed success. The US’s 2 percent inflation target did not prevent 9 percent inflation two years ago, while Europe’s similar target could not prevent inflation exceeding 10 percent. Consequently, inflation targeting has proven to be a relatively weak constraint.

Q: How did countries perform under free banking systems?

A: Free banking, characterized by competitive currency issuance by commercial banks, existed in several regions. Scotland, where three banks still issue currency, and Northern Ireland, with four such banks, are notable examples. In contrast, central banks in the US and England monopolized currency issuance.

Free banking systems thrived where restrictions on banks were minimal, allowing them to raise capital and expand branches freely. Banks had to compete for customers’ trust, leading to strong capitalization and competitive interest rates. In this decentralized system, banks issued notes redeemable for gold or silver, similar to modern-day bank-issued checking accounts.

Adam Smith, in “The Wealth of Nations,” highlighted the success of Scotland’s free banking system, which enabled economic growth by substituting coins with banknotes, facilitating trade and wealth accumulation.

Q: What happened to Scottish notes when the Bank of England suspended the gold standard?

A: During the Napoleonic Wars, the Bank of England suspended convertibility to gold, causing the Scottish banks to temporarily de-peg from gold while maintaining a fixed exchange rate with the Bank of England. Despite the breach of contract to pay in gold or silver, there were no legal challenges, and convertibility resumed alongside the Bank of England.

Q: Can you provide insights into Canada’s free banking system?

A: Canada’s banking system, governed by national law, allowed banks to branch across provinces, resulting in strong, diversified banks with fewer failures than the US system. Unlike the US, which experienced frequent financial panics, Canada enjoyed stability and served as a model for US reformers. However, political resistance from small banks hindered the adoption of branch banking in the US, leading to the establishment of the Federal Reserve System instead.

Q: Why was the Bank of Canada established in 1935?

A: The Bank of Canada was established during the Great Depression, despite opposition from Canadian bankers who felt no need for a central bank. Political motivations and the desire for inflationary policies drove its creation. While central banks worldwide struggled during the Depression, Canada’s banking system remained resilient, with no bank failures during the period. The Bank of Canada initially played a limited role compared to the Federal Reserve, with private interbank clearing continuing until the 1970s.

Post-1971, the Canadian dollar depreciated against the US dollar, with the Bank of Canada’s performance fluctuating in line with the Federal Reserve’s. Nevertheless, Canada’s banking system has remained robust, avoiding the housing bubble that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis.